Searching for Trump in Literature

Storms are sweeping over the world today, from the war in Ukraine, to the rise of Trumpism and its unbridled and unrestrained form of capitalism that violates all laws, to what feels like cataclysms in Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey. All together, these are signs of the emergence of a terrifying, amoral, and lawless phase in our collective, global history.

What happened in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, Venezuela, Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh (in Syria’s Aleppo), are marks of an era of putrid madness. We no longer live in a world where law, in its classical sense as defined during the Enlightenment, exists; neither domestic nor international law.

This reality, a return to pre-Enlightenment, has always existed as a low-lying possibility within the history of modernity.

The central difference, however, is that the old kings had limited power and limited influence on the globe, while Trump can directly impact the world’s moral and political landscape.

Trump, in an interview with the New York Times on January 9, 2026, spoke his convictions clearly: international law cannot set limits to his authority; the only limit is “his own morality and mind”. This belief about power and law is reminiscent of ancient emirs and kings who, apart from their own perceptions and moral compass, did not recognize any law. The central difference, however, is that the old kings had limited power and limited influence on the globe, while Trump can directly impact the world’s moral and political landscape.

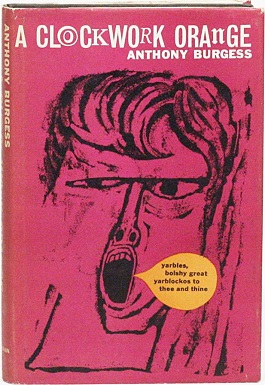

Trump allows himself to violate every law seemingly because he finds pleasure in doing so and because he wants to show that he is able to do so – an attitude which might as well be accompanied by the quote “What I do I do because I like to do,” made famous by The Clockwork Orange’s Alex DeLarge.

Here, it’s worth highlighting a concept introduced by German philosopher and Nazi Party member Carl Schmitt: the state of exception – similar to a state of emergency, where decision-making and state power are centralized for the survival of the state. One main difference, however, is where power is concentrated in this state: “The sovereign is he who decides on the state of exception.” Trump regularly pushes the world toward the state of exception to prove that all power and supremacy belong to him.

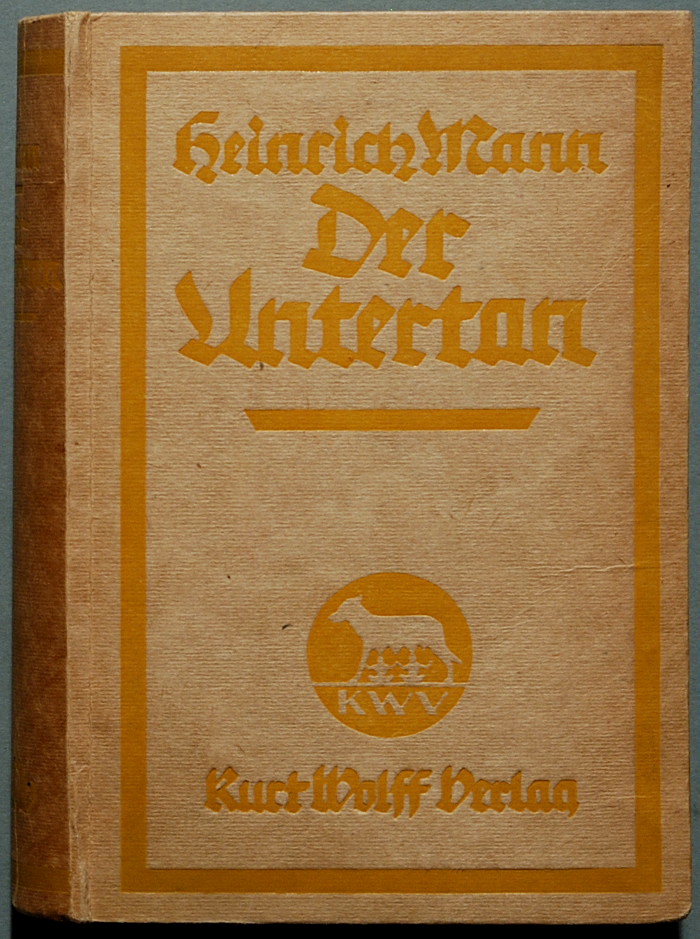

This kind of “goodbye to the law” attitude and disregard for any order isn’t unique to Trump. Look at the rhetoric of some billionaires, like Peter Thiel, a PayPal co-founder and an influential mentor to J. D. Vance, who links modern technological power to a set of ancient religious myths. It points to the rise of a new elite that places no value on humanistic principles and wants to operate in a more lawless world, where no force can stand in their way. This archetype is well-illustrated by Heinrich Mann’s character Diederich Hessling, who has no genuine belief in law, justice, or citizenship. For Hessling, these are merely instruments for self-advancement and accumulating power.

Trump, and the political elite behind him, are paving the way for a political system stripped of what you might call “humanistic” ethics.

This shift from law to lawlessness has created a deep sense of insecurity and confusion within Western societies. For the past two hundred years, what has most distinguished the West from other civilizations is the central place of law within it. In many other parts of the world, societies still aspire to establish the rule of law, while in the West itself, clear signs of its retreat in the United States and some EU countries have created a new global crisis.

The rise of a form of governance signals the weakening of one of its central pillars. Trump, and the political elite behind him, are paving the way for a political system stripped of what you might call “humanistic” ethics.

In the global south, we feel the danger of this shift more sharply than almost anywhere else, and one of its starkest signs is Trump’s admiration for a terrorist like Ahmed al-Sharaa.

This isn’t the first historical failure of Western humanistic morality. It has been challenged in several major moments in the past. But it has arguably never faced as much doubt and scrutiny as it does today, at least not since the Second World War.

Here, we must distinguish between two different kinds of law-breaking: anarchist law-breaking and fascist law-breaking.

Initially, those who most openly raised the flag of rebellion were largely libertarian writers, for whom breaking the law was always part of a broader rebellious agenda. Culturally, respect for the law has usually been a conservative tradition. But when conservatives themselves turn away from the law and become its enemies and violators, we cross the line from liberal conservatism into the realm of fascism. Conservatives do not abandon the law to expand freedoms; on the contrary, they abandon it to inflate the scope of violence, militarism, and expansionism.

Conservatives, in principle, demand that ordinary people submit to the law, yet for themselves, breaking the law is an often-used instrument within their toolkit, used to brandish impunity and display power.

An anarchist rejects the law because it is made by the powerful and often serves those in power. But when the right wing rejects the law, the action is usually rooted in the belief that the law protects the powerless and limits the growth and expansion of power; so, they treat it as an obstacle to their projects.

Fascist law-breaking grows out of a devotion to power and violence, feeds chauvinism and racism, and runs against the democratic spirit. Conservatives, in principle, demand that ordinary people submit to the law, yet for themselves, breaking the law is an often-used instrument within their toolkit, used to brandish impunity and display power.

Diederich Hessling

Diederich Hessling, the central character in Heinrich Mann’s novel The Loyal Subject (Der Untertan), one of the major works of early twentieth-century German literature, functions as a sharp, early portrait of the kind of personality societies can produce in the years leading up to fascist rule.

When Mann began thinking about writing the novel, he initially wanted to create a positive heroic figure. While writing in Berlin, in letters he sent to Thomas Mann, he wrote that living among a “herd of slaves with no ideals” felt suffocating, and that this bleak atmosphere pushed him toward imagining a genuinely humanistic protagonist. But he also insisted that before he could create such a figure, he first had to present the ugly example: a character who embodies the complete opposite of the positive hero.

Diederich Hessling is the clearest example of that opposite figure. He is a fanatical supporter of German Kaiser Wilhelm, submissive and obedient to those above him, and deeply attached to discipline and control, yet inwardly weak and cowardly. He despises books, concerts, and theatre. Raised by a violent father, he learns to bow before his superiors while becoming ruthless and merciless toward those weaker than himself. When he takes over his father’s paper factory, he quickly begins tightening rules and threatening the workers. Politically, he harbors an intense hatred for social democrats and liberals, dismissing them as weak, blaming them for Germany’s decline, spying on them, and reporting them to the police.

He brings the same mentality into his relationship with Miss Agnes Göppel. Agnes, the daughter of a liberal factory owner, is everything Hessling is not: romantic, independent, and opposed to authoritarianism. Hessling sees in Agnes a free and independent girl and fears her open and free personality. He wants to pull her into his own world and reshape her to admire “nation,” “power,” and “discipline,” because he can only truly respect strength and interprets Agnes’s tenderness as weakness.

Hessling’s treatment of Buck, another key character in the novel, is a true window into his moral world. Buck is a liberal who refuses to be subdued or turned into a subordinate. He thinks rationally and makes his own choices; a kind of independence is incompatible with Hessling’s ethic. When Buck faces difficulty, Hessling pushes him toward ruin, further highlighting Hessling’s lawlessness and his attitude: crushing “the weak” is something normal, even inevitable. An attitude which is echoed in moments of Trump’s speeches, where he often makes cavalier remarks toward his opponents, risking their lives, and at times even toward members of his own party who have stood up to him.

Alex DeLarge

Alex DeLarge, the protagonist of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, is an even more unsettling and, in some ways, more important example than Hessling. For Alex DeLarge, violence is not tied to any concrete need. It is a way of feeling alive and proving himself. His brutality is not rooted in ideology or belief; it is violence for its own sake: “What I do I do because I like to do.” If Alex is capable of violence, then why not be violent?

Burgess’s protagonist sees violence as an aesthetic experience, one that turns him into a ruthless and merciless predator. Yet his violence is self-generated rather than political. It is personal pleasure, not a programmed belief or in the service of an agenda.

To create contrast, Burgess uses a different kind of violence to serve as the story’s antagonist: the systematic, institutional violence of the state, which seeks to reshape people into obedient, robot-like beings through total control. The novel invites a comparison between Alex’s spontaneous, “natural” brutality and the state’s bureaucratic, organized, and deeply unnatural coercion. Alex is not ignorant or dull; he is a sharp adolescent who loves Beethoven. His savagery, in other words, cannot be explained away simply as the product of family or culture. He treats it as a game, something thrilling, even enjoyable.

In the novel, Alex goes through a long process to understand that individuals do not have the right to be violent, and that the state is the monopolizing force for violence to put individuals under pressure and remake them in its image. Alex is made to understand that the state and its bureaucratic machine is a force larger than him.

State power is the means and method of today’s political reality. So, what if a superpower like the United States, a force akin to a vast machine packed with terrifying weapons, starts behaving like Alex? What happens then?

Examples like Roman Emperor Caligula and his reign may come to mind, but it would not exactly be right to say a Caligula-like state has emerged. Caligula was a bloodthirsty ruler with little respect for law or restraint, but unlike today’s U.S. state, he had neither nuclear weapons nor a military equipped with modern technology capable of unspeakable horrors at a global level.

What threatens the world today is the possibility that the moral compass of figures like Hessling and Alex DeLarge becomes the moral compass of superpowers. There are already signs of this: the schadenfreude and pleasure in destruction, coupled with contempt for law, is beginning to operate as alternative forms of law, and powerful states are beginning to act like predators in a jungle.

So, given our new lived-reality, are we now living in a world of lawless Hesslings and unbound Alex DeLarges?

Bachtyar Ali

Bachtyar Ali, a leading novelist, poet, and essayist, is celebrated as one of the most influential contemporary Kurdish authors. Best known internationally for The Last Pomegranate Tree, he has published over 40 works of fiction, poetry, and criticism, including 12 novels. His writings have been translated into numerous languages, from Arabic and Persian to German, Italian, and English. In 2017, he became the first author writing in a non-European language to win the prestigious Nelly Sachs Prize.