Violence in Homs Rekindles Sectarian Fears in a Fractured Syria

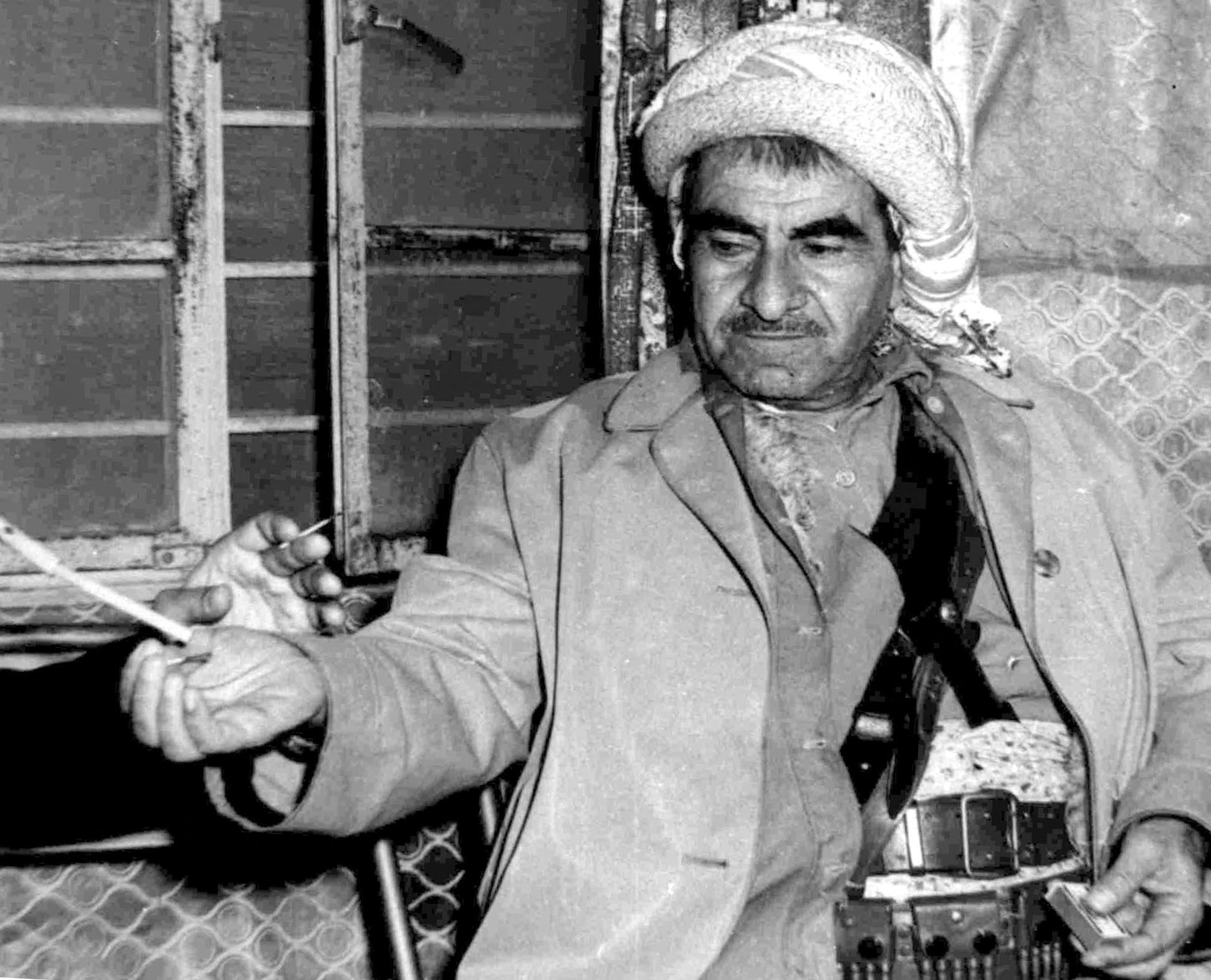

Member of General Security at a checkpoint in the vicinity of the predominantly Alawite neighborhoods of Al Nuzha and Al-Zahra in Homs | Picture Credits: Santiago Montag

Violence erupted in the Syrian city of Homs in November 2025 after the killing of a Sunni couple triggered retaliatory attacks on Alawite communities, raising worries of continued sectarian conflict. Now Syria’s minorities say they are afraid of further escalation, with some considering leaving the country.

Around 4 AM, Sunday, November 23, Abdullah al-Aboud, an imam from the Bedouin Bani Khalid tribe, headed to his neighborhood mosque in the village of Zaidal – east of Homs – for the morning prayer. Strangely, the building was closed, according to witnesses. Then, neighbors heard a woman screaming for help, but her cries stopped just as abruptly as they had started. Upon entering the al-Aboud’s home, neighbors found Abdullah’s corpse with his skull completely shattered, his wife burned to ashes, and a sectarian message – crudely written and pointing to the Alawite faith – spray-painted on the wall.

The same day, fueled by anger, members of the al-Aboud’s Bani Khalid tribe stormed the predominantly Alawite neighborhoods of al-Nuzha and al-Zahra, and destroyed shops and set fires to homes, before waiting for the results of the investigation launched by the Syrian Interior Ministry. They threatened many residents, blaming them for the murders while chanting sectarian slogans. Some of the slogans accused the Alawite community of supporting Bashar al-Assad, due to the former dictator’s Alawite identity.

The Interior Ministry Spokesman Noureddine al-Baba has since stated, “There is no physical evidence that the attack was sectarian.” This was also echoed by Morhaf al-Naasan, head of government internal security forces in Homs, who stated that the murder of the couple appeared “aimed at fueling sectarian divisions and undermining stability in the region.”

“They came down Avenue 66 and the al-Muhajirin neighborhood [in Hama],” said Fadi Khadour, 48, owner of a fast-food shop. “They fired a shot at every house, threatening everyone,” he added as he helped workers replace the broken window of his restaurant. “They forced many people to leave their homes, some even had them taken over,” he said to The Amargi.

General Security and Special Forces flooded the city to bring the situation under control, and clashes and civilian evacuations continued until 5 PM. After stabilizing the situation by nightfall, they imposed a citywide.

“We are afraid to go back because they threatened us by name. We know this isn’t over, it will happen again”

Ali Ahmed, 50, a resident of Zahra, said, “Government forces protected us, we even saw them fighting hand-to-hand with them.” He and his family fled their home after hiding in the bathroom for hours. “We are afraid to go back because they threatened us by name. We know this isn’t over, it will happen again,” he said, holding his daughter with tears in his eyes. “My family supports the new government, but we feel unsafe. We are planning to leave the country, but right now we have nothing to make that possible,” he said to The Amargi.

Ali also noted that the attackers were not members of the Bani Khalid tribe. “Some people took advantage of the chaos to take what is not theirs,” he said, referring to houses that were seized during the attacks.

Bedouin Pain

Northeast of Homs lies the Bedouin neighborhood in al-Saan. Among the traditional Bedouin tents of Arab shepherds, a particularly large one had been set up, hosting a funeral for the murdered couple. Sitting inside was Sheikh Faisal al-Basha of the Bani Khalid tribe; in an exclusive interview with The Amargi, he condemned the attacks in central Homs:

“I do not accept this behavior under any circumstances,” the Sheikh said. “Many reacted violently without waiting for the investigation,” he explained while surrounded by the couple’s close relatives. “I am grateful that I was able to restrain my people and that no one was killed; otherwise, things would have spiraled out of control.”

Talking to us, but addressing those around him, he expressed hope for the investigation: “The government investigation will find whoever is responsible, so justice can be done. I will not allow anyone to take revenge on an entire community.”

“We Need Help”

A day after the events of November 23, prominent Alawite religious figure Sheikh Ghazal Ghazal, from the Supreme Alawite Islamic Council in Syria and Abroad, made a statement accusing the Interim Government of fanning the flames of sectarian conflict. In the aftermath of the statement, protests broke out in the Alawite-majority coastal regions of Latakia and Tartus.

The coast was the site of the first major crisis under al-Sharaa’s Interim Government, when the crackdown on pro-Assad armed groups resulted in large-scale civilian massacres. Since al-Sharaa came to power, the country has faced near-continuous tension and violence due to sectarian and personal vendettas.

In the last twelve months alone, the coastal region has suffered around 1,500 casualties. Recently, six perpetrators were tried out of the more than 500 who were identified.

During the protests, hundreds of people demonstrated peacefully to demand security, the release of detained relatives, and justice for the massacred civilians. In Homs too, despite the imposed curfew, the Alawite community responded to the call made on social media by Sheikh Ghazal Ghazal.

“The protests are not only about what happened on Monday. They are a response to what we have been living since December, every day someone from our community is killed.”

Another Alawite sheikh, who preferred to remain anonymous, mentioned the murder of two young men just days earlier. Speaking to The Amargi, he said, “The protests are not only about what happened on Monday. They are a response to what we have been living with since December; every day, someone from our community is killed.”

“It is true that the General Security protected the demonstrators; we exercised our right to protest. But we know the risks were high,” the Alawite sheikh admitted anxiously before stressing the peaceful nature of the demonstrations. “We have no weapons, we don’t respond when we are attacked so as not to generate more violence, what do they expect us to do? Taking to the streets to protest peacefully is all we have left. This is our country; we also want to live in peace.”

In his statement, Sheikh Ghazal Ghazal called for a decentralized system of government in Syria – a solution that some protestors have also echoed.

Enduring Fragility

Homs has historically had a leading role in the country: there has been social cohesion within its diverse ethnic and religious communities, it emerged as an industrial city in the 1970s, and was a capital of the 2011 uprising against Bashar al-Assad, despite crackdowns by Assad loyalists. During the war, Assadists’ presence and Homs’s prominence made the city a victim of sectarianism, leaving a legacy of violence that is deeply polarizing and hard to heal from.

In the post-Assad era, Homs has become a center of vengeful attacks. Although al-Sharaa’s Interim Government labels the perpetrators “outlaws,” the underlying issues are more complex than simple criminality: the city has witnessed dozens of silent killings since December 2024, community-based violence has surged, and the Interim Government has been either unable or unwilling to enact transitional justice. The absence of institutions capable of mitigating or resolving underlying problems has allowed revenge to be meted out almost unhindered, and tribal law to assume a sovereign role.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), in October alone, there were 17 murders among the Alawite community in the province, the highest number in the country that month. This snapshot reveals only a fraction of the reality, as many attacks go unreported out of fear. Unless political measures are taken to address the social and psychological wounds, this could lead to more bloodshed. Homs, with its regional particularities, reflects Syria’s current problems in this new era – an era beginning with hope but now cradling violent uncertainty.

Santiago Montag

International journalist and photographer based in Damascus