Are the Kurds facing another 1975?

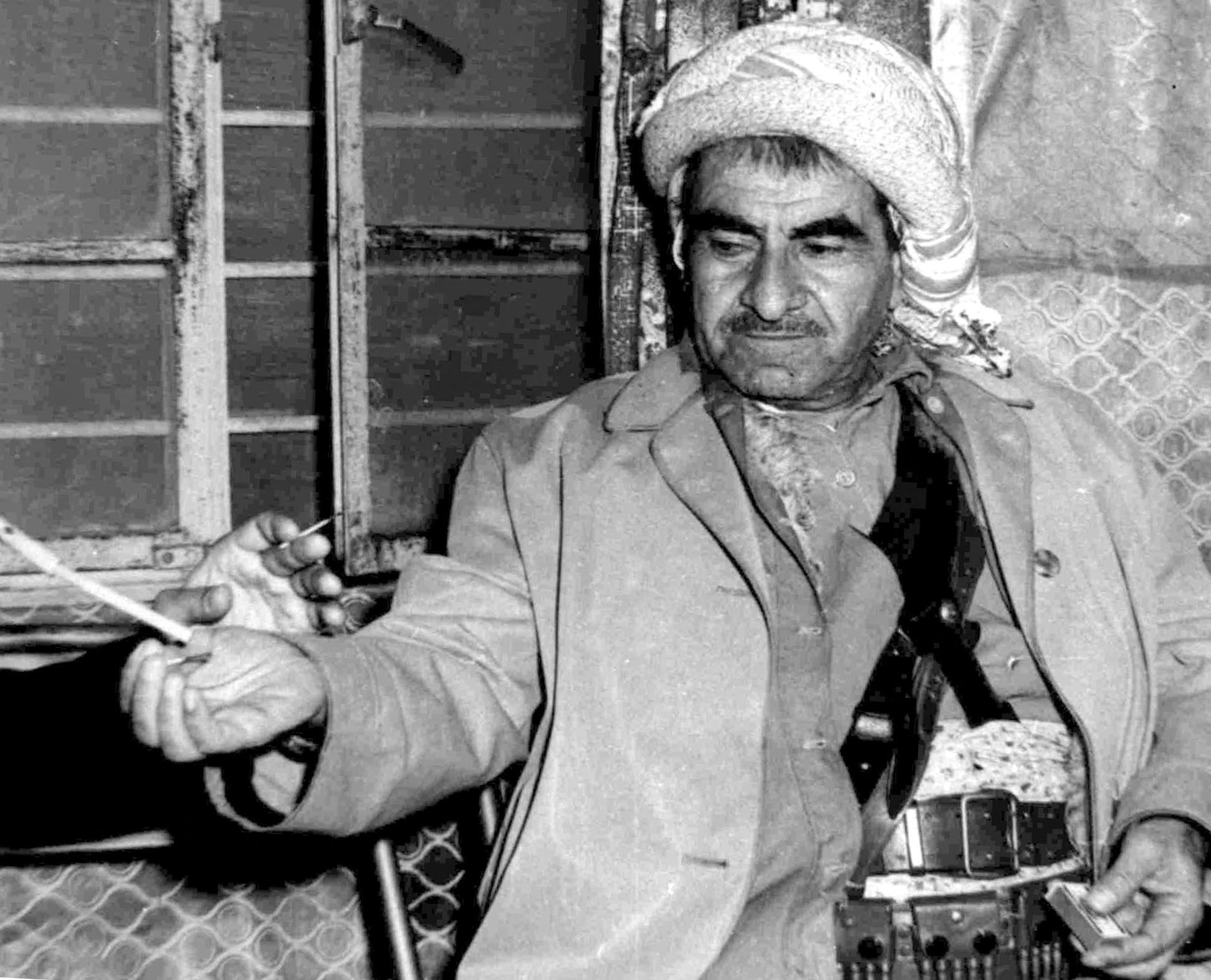

An undated picture taken in the 1960s in the Kurdish mountains of northern Iraq shows Kurdish leader Mulla Mustafa Barzani. Mulla Mustafa died in the United States in 1976. (Photo by AFP)

Many Kurdish political and media activists hold the view that it is the leftist ideology of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), and by implication the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), that is the main cause of Rojava’s strategic international isolation. Accordingly, they argue that it is Rojava’s socialist ideology that explains the abandonment of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) by the US and Western governments and Israel’s muted response to the unfolding of catastrophe in Rojava.

This view is fundamentally flawed.

“One could argue that the present moment resembles 1975: Jolani is Saddam Hussein; Tom Barrack is Henry Kissinger; and Mazloum Kobani is Mullah Mustafa.”

Politics in general, and international politics in particular, is primarily shaped not by ideology but by strategic interests. For the still dominant realist and liberal schools of International Relations (IR), strategic interests include maintaining security, increasing geopolitical power, and gaining economic advantages. Securing these interests often takes the form of a relentless pursuit of state power.

This view of international politics is challenged by critical IR, which argues that there are deeper social dynamics at work in international politics. But if for now we stick to mainstream IR, we can indeed find numerous examples of how the pursuit of strategic interests has been in direct contradiction with the ideological orientations of international actors involved in particular conflicts or processes.

“International politics, then, is grounded in the pursuit and expansion of strategic interests. What Kurdish political leadership has almost always failed to grasp properly is the complexity of state interests in the international arena and the tactical fluidity of the means through which those interests are pursued.”

For more than a decade, the United States indirectly fought the Soviet Union by supporting Afghan jihadists some of whom later formed the al-Qaeda and carried out the 9/11 attacks. Islamist Iran supported Christian Armenia against Shiʿa Turkic Azerbaijan for more than thirty years. During the 1980s, Iran also supported the Kurds of Iraq while brutally suppressing Kurds in Iran. After US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iran also sheltered anti-Shiʿa al-Qaeda leaders and provided military and logistical support to anti-American Sunni forces in Iraq, forces that were Iran’s enemy ideologically. The United States facilitated Khomeini’s victory in Iran – and the rise of political Islam in the Middle East – by forcing the Shah’s army to refrain from crushing the revolution in a manner that the Islamic Republic dealt with recent anti-government protests in Iran. The Soviet Union allied with Arab nationalist states in Egypt and Iraq which massacred pro-soviet communists. Rojava fought ISIS alongside and with the significant support of the US military, even though from the perspective of Rojava’s radical left ideology the US was defined as an imperialist power. And the list goes on.

International politics, then, is grounded in the pursuit and expansion of strategic interests. What Kurdish political leadership has almost always failed to grasp properly is the complexity of state interests in the international arena and the tactical fluidity of the means through which those interests are pursued.

In Syria, American strategy was fundamentally informed b Trump’s isolationist America Frist posture. This strategy was based on two pillars: reducing military commitments in the Middle East and eventually withdrawing its forces from the region and permanently blocking the return of Iranian influence to the Levant. A Sunni state under the tutelage of NATO member Turkey was ideal for this purpose. The legitimacy and survival of such a state depended on al-Sharaa’s government gaining access to oil and gas resources in areas controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and on the postwar reconstruction of Syria—something that could be made possible through massive investments by Gulf Arab states and the involvement of Turkish construction companies.

Moreover, the trade and economic relations of these Arab states with the United States are worth trillions of dollars, making it imperative for Washington to take their preference for consolidating al-Sharaa’s government into account.

The main obstacle to implementing this plan was that Israel viewed the consolidation of a Sunni state close to Turkey as a threat. And indeed, in the early months after Assad’s fall, Israel and Turkey were set on a collision course in Syria.

The US addressed the concerns of Turkey, al-Sharaa, and Israel by securing agreement among all parties on a de facto partition of Syria, one that defined a southern sphere of influence for Israel and a northern sphere of influence for Turkey.

The creation of these spheres of influence logically required the US to abandon Rojava in order to satisfy Turkey and al-Sharaa. In return, the al-Sharaa–Turkey axis acquiesced—at least in the medium term—to de facto demilitarisation of areas south of Damascus and Israel’s newly acquired control over Mount Hermon and other areas on its border with Syria and Lebanon in the immediate aftermath of the Assad’s fall.

Turkey was also compelled to refrain from deploying air-defence systems and radars in southern Syria near Israel’s borders, enabling Israel to maintain control of southern Syrian airspace for potential future strikes against Iran.

This multilateral bargain constituted the new fundamental equation in Syria; one that Rojava’s leadership failed to understand in a timely and adequate manner. Consequntly, it failed either to adapt to or to attempt to redefine it.

US recognition of the transitional government of Syria led by Ahmad al-Sharaa, a former al-Qaeda leader with a US bounty on his head, and Trump’s subsequent meeting with al-Sharaa and the lifting of US sanctions on Syria, should have sounded alarm bells for Rojava’s leaders; or, at the very least, from the moment Syria’s transitional government was admitted into the anti-ISIS coalition it should have been clear that US military support for Rojava was coming to an end.

“Rojava’s leadership did not push hard enough for political recognition by the United States.”

It is worth recalling that the United States never engaged with Rojava at a political level and always regarded it merely as a military partner within a counter-terrorism framework. Accepting this arrangement was itself another major mistake: Rojava’s leadership did not push hard enough for political recognition by the United States. Indeed, Rojava’s experience was marked by a stark disparity between the success and efficiency of its military wing, SDF, and the international invisibility and inefficiency of its political wing, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

But let us, despite the argument above, assume that it really was Rojava’s leftist ideology that caused the lack of U.S. and Israeli support. But then the question arises: were the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iraq (PDK) leftist as well when the United States openly opposed the 2017 independence referendum in Iraqi Kurdistan, at a time when the blood of Peshmerga fighters killed in the war against ISIS had barely dried? Was Mullah Mustafa Barzani a leftist when the United States abandoned him in 1975 leading to death and displacement of tens of thousands of Kurds?

The answer is clearly no. In fact, one could argue that the present moment resembles 1975: Ahmad al-Sharaa is Saddam Hussein; Tom Barrack is Henry Kissinger; and Mazloum Kobani is Mullah Mustafa.

Nevertheless, even the strategic errors of Kurdish leaders ultimately stem from Kurdish statelessness—from the reality that Kurds are a non-state actor in a world structured around states.

Yet if the post–Second World War international political and legal order once defined existing political borders as sacred and immutable and enforced that definition with full force, that order is now collapsing: Russia annexes large parts of Ukraine with no effective objection from the US, and the US itself seeks to annexe Greenland and even Canada.

The US as the key enforcer of the basic rule of state sovereignty in postwar internarial relations is breaking them in the most monumental fashion. And there will be many middle-power states, such as Turkey, Pakistan, and Iran, which would follow the example. Turkey already de facto annexed large swaths of Syrian and Iraqi territory.

A new era of geopolitical accumulation has begun, and if the Kurds fail to understand this, they will suffer further blows.

Kamran Matin

Kamran Matin is an Associate Professor of International Relations at the University of Sussex, UK, specialising in historical sociology, international theory, nationalism, and Iranian and Kurdish politics and history. His current research focuses on the theory of ‘uneven and combined development’ (UCD), nations and nationalism, and non-Western colonialism. He is the co-author of Queer Identities in Migration: Iranian Journeys (Bristol University Press, 2026), the author of Recasting Iranian Modernity: International Relations and Social Change (Routledge, 2013), and the co-editor of Historical Sociology and World History: Uneven and Combined Development over the Longue Durée (Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016). He has also published numerous articles, commentaries, and op-eds on Kurdish and Iranian politics. He is a non-resident fellow at the Kurdish Peace Institute in Washington, DC, and a research associate at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg.