Syria: Questions Raised as the Trial for the Alawite Coast Massacres Begins

SYRIA, Aleppo, November 18th, 2025.

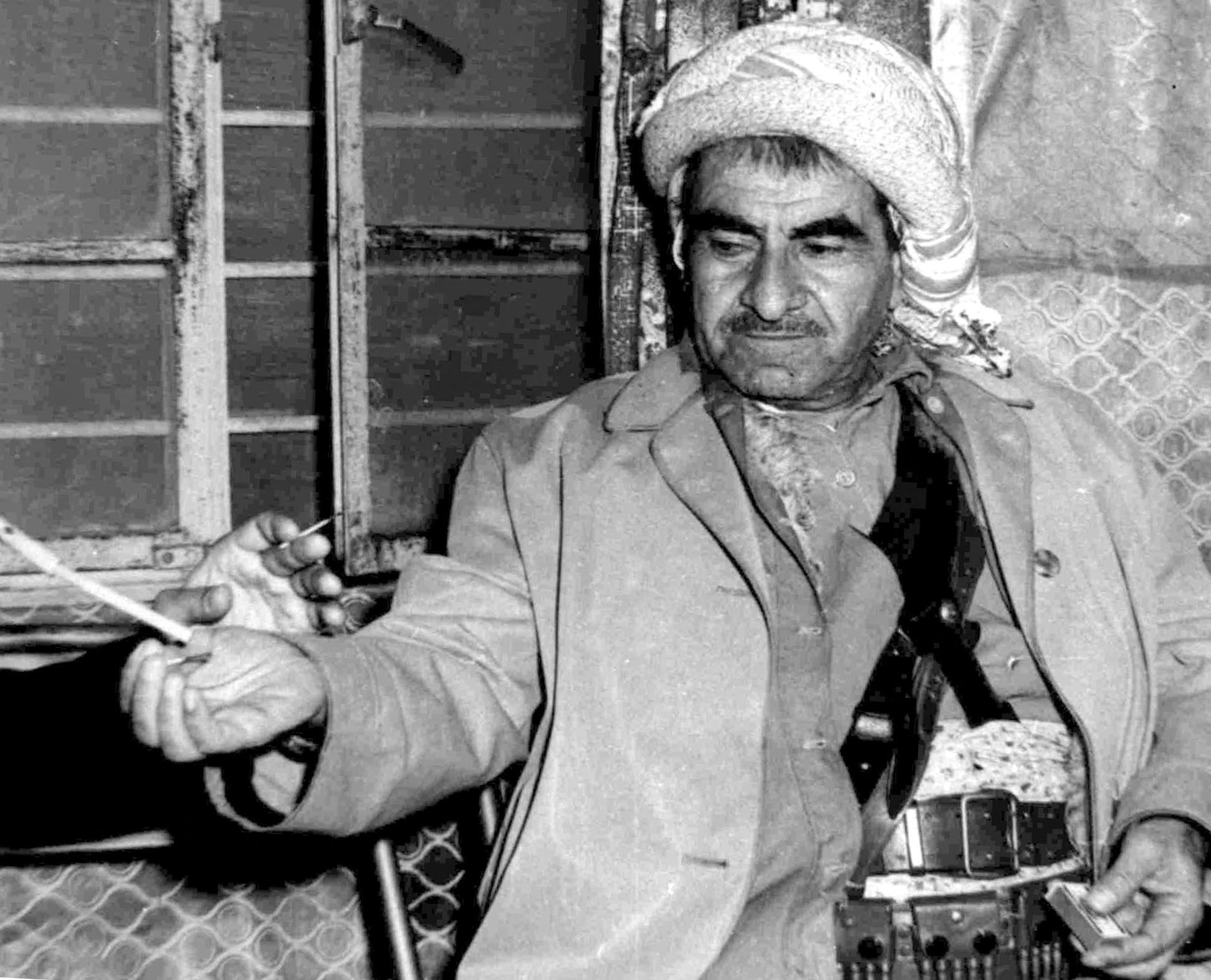

At the Aleppo courthouse, first day of the trial judging crimes against civilians and the general security that occurred in march 2025 in the coastal region. 7 members linked with the ministry of defense and 7 members of the pro Assad insurgency were brought to court.

The court during the hearing.

The court during the hearing | SYRIA, Aleppo, November 18th, 2025 | Picture Credits: Charles Cuau

Aleppo experienced a historic day on November 18, according to Syrian officials. Members of the new security forces and supporters of the former regime were put on trial for the massacre on the Alawite Coast: 14 men stood before the court on the day, but authorities say a total of 563 people will be tried eventually.

With literal golden scales in hand, Baraa Abderrahmane, spokesperson for the Syrian Ministry of Justice, quietly walked toward a courtroom on the first floor of the Aleppo Palace of Justice. Syria’s new rulers want to demonstrate a clear break from the decades-long reign of the Assad dynasty, which ruled through violence and repression. They want to mark, visibly and publicly, the arrival of a justice system that claims to be independent, transparent, and accountable. But as the clock ticked on inside the courtroom, and voices rose outside its doors, questions began to emerge.

The massacre, which took place on March 7—9, claimed over 1500 civilian lives – mainly from the Alawite minority.

The massacre, which took place on March 7—9, claimed over 1500 civilian lives – mainly from the Alawite minority. Both sides, the new Ahmad al-Sharaa-led government in Damascus and former regime supporters, have since then accused each other of being behind it.

The charges against the remnants of the former regime are plenty: incitement, fueling sectarianism, hatred, leading or joining armed gangs, and carrying out attacks on military and government forces. Those affiliated with the new authorities face accusations of premeditated murder and abuses against civilians during the same coastal events.

Before questioning began, Judge Zakaria Bakkar, president of the court, reminded the room of the rules governing a public trial, a necessity after the fall of the dictatorship. His words were measured, almost ceremonial: “The court is sovereign and independent.”

Seven defendants accused of attacking security forces entered first. Their wrists were bound with plastic ties. They were placed in a black booth with only a barred door through which they could make their voices heard to answer the judge’s questions. The interrogation lasted just over an hour.

“After so many years of dictatorship, transparency is essential. We need to know who is being tried and why.”

After a small break, the security officers of the new authorities were brought in, without handcuffs, wearing caps pulled low to shield their faces from photographers. Unlike the former group, their identities were not protected for long: the entire trial was being broadcast live, and their names and hometowns quickly rippled across Syrian social media.

Outside the courthouse, reactions were mixed. Some said this visibility is necessary: “After so many years of dictatorship, transparency is essential. We need to know who is being tried and why,” argued a middle-aged man who preferred to remain anonymous. Others feared that broadcasting the names of the accused before any verdict could inflame tensions or turn the process into public humiliation rather than due process.

During the two-hour trial, one defendant argued – replying to the judge who asked him to explain the words he spoke in a video – that the evidence used against him is fabricated and the video, “a product of artificial intelligence.”

Another, when asked about why he previously confessed, said he was “afraid of torture.” Judge Zakaria Bakkar replied that he had not heard of any cases of torture and that, as a judge, it is not something he resorts to.

Some defendants, who were part of militias affiliated with the new authorities, insisted they acted against the “foulouls” – a term commonly used to refer to remnants of the former Assad regime. The judge cut them off sharply. “I will not accept that term. All defendants here are Syrians who committed violations against Syrians,” he said.

It was a rare attempt to flatten the political divide inside a country fractured by fourteen years of war. But whether the court could truly hold all sides to the same standard remained a central question.

Some members of the defendants’ families made the trip to attend the trial. One woman came to support her son-in-law, who is accused of attacking law enforcement officers. Speaking to The Amargi preferred to remain anonymous for her own protection, “He is innocent,” she insisted. “They wanted to blame him out of revenge. I know he didn’t do anything.” She paused before adding, “I don’t know under what conditions he confessed the first time.” She hoped he would be released, and believed Syria must “move on and focus on reconstruction”. If convicted, some of the defendants could face the death penalty.

At the end of the first day’s proceedings, Rami Hanji, a lawyer at the Aleppo bar, welcomed the conduct of the trial. He represents members of both the current security forces and supporters of the former dictator and wants to see it as “proof of his integrity and impartiality […]. The very fact that this trial is being held, for the first time in Syria, publicly is clear evidence of the government’s decision to implement justice under the eyes of both local and international media,” he said.

While some see the trial as a step in the right direction, others point to what is missing: no accountability for the ongoing repression in the Druze province of Suwayda, and no prosecutions for the crimes committed by Bashar al-Assad and his loyalists.

He claimed to have seen no procedural irregularities. But in a trial and political quagmire, where each side accuses the other of being responsible for massacres, such a position raises a question: How can one represent and defend both sides?

And What About Bashar?

While some see the trial as a step in the right direction, others point to what is missing: no accountability for the ongoing repression in the Druze province of Suwayda, and no prosecutions for the crimes committed by Bashar al-Assad and his loyalists.

In the courthouse lobby, a man, seeing the journalists, approached to ask, “You’re here for the trial?” before adding: “How are they already facing justice when Bashar al-Assad’s torturers are still walking free?”

He is 45 years old and has spent much of his life behind bars; fifteen years under Hafez al-Assad’s regime and another year under Bashar al-Assad’s, in the notorious Saydnaya prison. He had already come to the Palace of Justice to file a complaint against those who imprisoned him. Officials told him that proceedings in his case had not yet reached the investigative stage, but that he could submit a petition.

“Where is justice? It has had no place for me so far,” he complained.

If the first day of hearings offered few answers, it also revived old questions and sparked new doubts about the Syrian justice system. For some, the process appears more performative than substantive; for others, it seems unequal in whom it chooses to judge. For now, Syrians will have to wait.

The Amargi

Amargi Columnist