Salvation and Control: Politics under Syria’s New Authorities

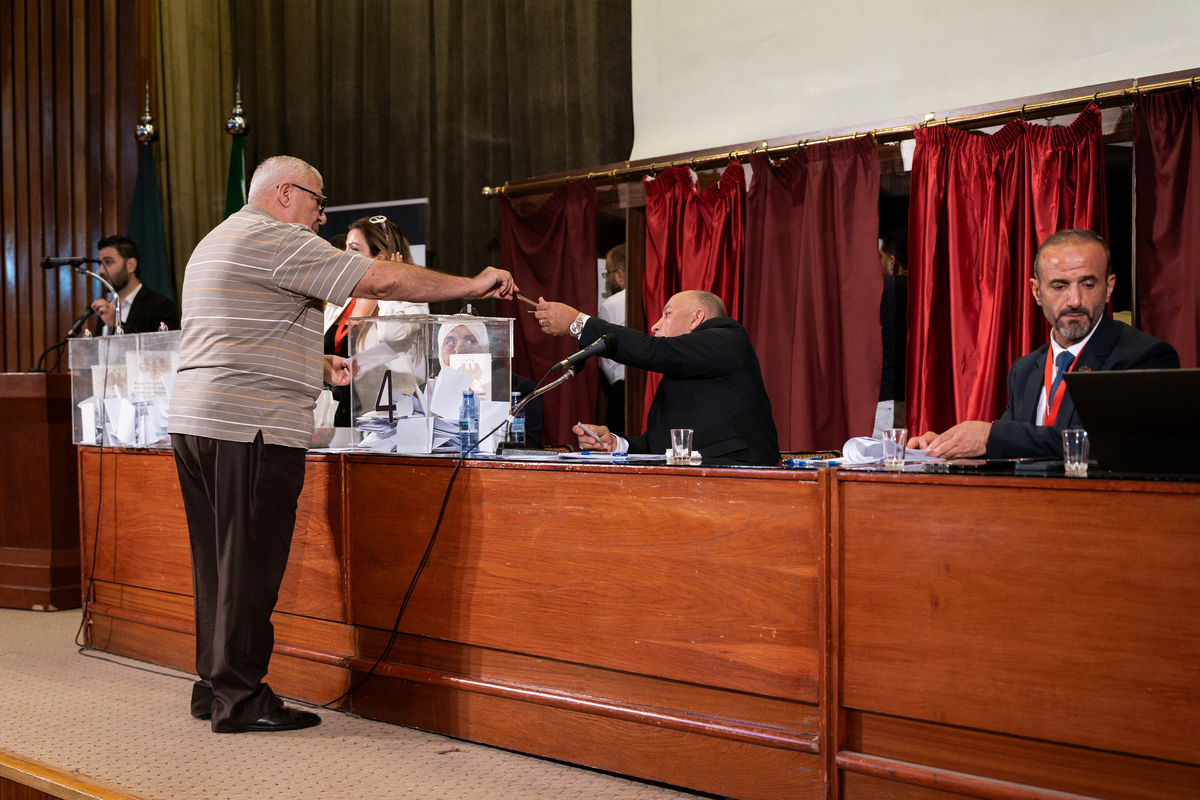

Voters cast their ballots in Syria’s parliamentary elections on October 5, 2025, to choose 121 of the 210 members of the People’s Assembly | Picture Credits: Pauline Gauer

Voters cast their ballots in Syria’s parliamentary elections on October 5, 2025, to choose 121 of the 210 members of the People’s Assembly | Picture Credits: Pauline Gauer

Syria holds its first election since the fall of the Assad regime. Progressive Syrians, unlike the small cadre of loyalists to the interim government, view the People’s Assembly elections not as characterising democracy, but as a recycling of the Assad-era authoritarianism.

The electoral body is monopolized, candidates are chosen based on loyalty, and the interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, gets to appoint two-thirds of the deputies. Meanwhile, cities with Alawi majorities, the Autonomous Administration in northern Syria, and Druze communities are left out. What is called an election becomes little more than a performative gesture that creates the illusion of democracy rather than engendering true political participation.

In the face of such farcical repetition of history, critical Syrians often resort to parody. This was recently evident in images circulating on social media depicting all elected members of the assembly as copies of Ahmed al-Sharaa, highlighting the incoherence between official rhetoric and reality.

Since Assad’s fall, Syria’s political landscape has revealed two facets under the interim government.. The first is the institutional discourse, employing neutral, technocratic language in discussions of constitutions, parliaments, and elections, that is primarily aimed at Western and regional powers. The second facet is that of a jihadist reality that rejects pluralism and reproduces domination in a fundamentalist guise. The latter feeds an unprecedented wave of hate speech. It deploys militias and security forces to exercise violence in the name of “ideological purity”, purging those who don’t fit their doctrine, whether secular, non-Sunni, or progressive. The killings in coastal Alawi communities, the Suwayda massacres, and the daily incitement against the Syrian Democratic Forces are a clear manifestation of this policy.

Syria’s political scene is thus structured around a coercive binary of “allegiance and renunciation”, a religious version of Carl Schmitt’s friend-enemy distinction. At the same time, the interim government in Damascus continues to engage in a superfluous diplomatic discourse about statebuilding, exemplified by Ahmed al-Sharaa and his foreign minister visiting various Western capitals and the United Nations.

In this political environment, social diversity in Syria is notably under threat. The foundations of coexistence are collapsing, and differences are being criminalized. Meanwhile, the interim government exploits Sunni victimhood for an authoritarian project of revenge and dehumanization, thus inventing a fundamentalist Sunni nation. Critical Syrian voices ask: Is Syria still capable of coexistence, or has its division become necessary to preserve what remains of human dignity?

The Chosen category

All these signs indicate so far that the interim government in Damascus embodies the opposite of a civil state. The international states’ acceptance of this model, justified in the name of ‘stability,’ along with the conflicting interests of regional powers, from Israel and Turkey to the Gulf states, will likely lead to further crises. It risks deepening divisions in Syria, given that this authority is based more on a salvationist drive than on the principles of citizenship and partnership.

/quote

It is worth examining the ideology of this group, particularly fundamentalist salvationism, that turns religion into a political project of salvation through violence. It embodies extreme political theology, sanctifying rule and legitimizing violent rituals to purge society of “differences.” Salvation here becomes a program of domination that turns exception into norm and violence into a condition of power. It has shifted from “armed jihad,” as a means of salvation through martyrdom and obedience, to “empowerment,” a theology of power that consecrates rule and makes Damascus the center of a new symbolic caliphate.

The Return of the Repressed

Public statements are merely an ideological mask hiding a pathological desire to purify and eliminate the “other” within society.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, this salvational behavior is better understood through the impulses of ‘the return of the repressed’ rather than through official propaganda. Public statements are merely an ideological mask hiding a pathological desire to purify and eliminate the “other” within society.

The idea of the return of the repressed, shown in waves of violence and the exclusion of others from politics, has deep historical roots. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Syrian nation-state was established in an incomplete manner, lacking any form of social contract that reflected the society’s diversity.. It was akin to a failed selective surgery, similar to many countries in the Middle East. The birth of the Syrian state went through French mandate control, the illusion of “independence and Arabism,” and repeated military coups, which ended with the rise of the Ba’ath Party, which arguably destroyed life in the political public spheres. All these traumatic events have repressed pluralism, democracy, and class conflict. It is this repression that has returned in the form of Sunni sectarian victimhood embodied by the interim government. It manifests in violent and vengeful actions whenever possible, especially in the absence of international law, internal political checks, or a civil constitution grounded in a social contract.

The election of the People’s Assembly is now just a formal event to maintain the existing power structure, instead of solving Syria’s major problems through institutional change and dialogue.

The Illusion of Legitimacy

For nine months, the interim government has relied on formalistic displays and the denial of reality. It has utilized the media to replace genuine political confrontation. From the dream of a “new Singapore” to the Damascus International Fair, as well as theatrical dramas involving the constitution, Ahmed al-Sharaa’s presence in New York, and the People’s Assembly elections, all aim to produce a false legitimacy.

Meanwhile, systematic violence, the exclusion of minorities, and daily violations continue. The neo-liberal economy and social reality indicate collapsing and corrupt structures, rather than being grounded in justice and diversity.

Western engagement with Syrian Salafi jihadism is based on a pragmatic logic aimed at granting legitimacy in order to impose “security and stability” at the expense of participation and rights.

Western engagement with Syrian Salafi jihadism is based on a pragmatic logic aimed at granting legitimacy in order to impose “security and stability” at the expense of participation and rights. However, reality reveals the opposite. The more this group gains external recognition, the more its violence and internal exclusion will increase. Legitimacy provides political cover that strengthens its repressive tools and undermines local diversity. Accelerating the elimination, rather than the alleviation of differences, becomes the inevitable result.

What is frightening about post-Assad Syria is not just the collapse of the idea of a participatory state but the exploitation of modern state tools—elections, a constitution, the army, and security—to impose a totalitarian model, exemplified by the imposition of Sharia law on all aspects of life under the interim constitution. The question remains: Can this model adapt to international oversight and the internal demands of Syrians, or will it continue its cycle of hysteria and exclusion, reproducing conflict and death to achieve the “salvationist idea”?

Ferhad Hemmy

Ferhad Hemmi is a journalist and researcher from Kobanî, Syria. He has written extensively on the Kurdish question and the politics of the Middle East.