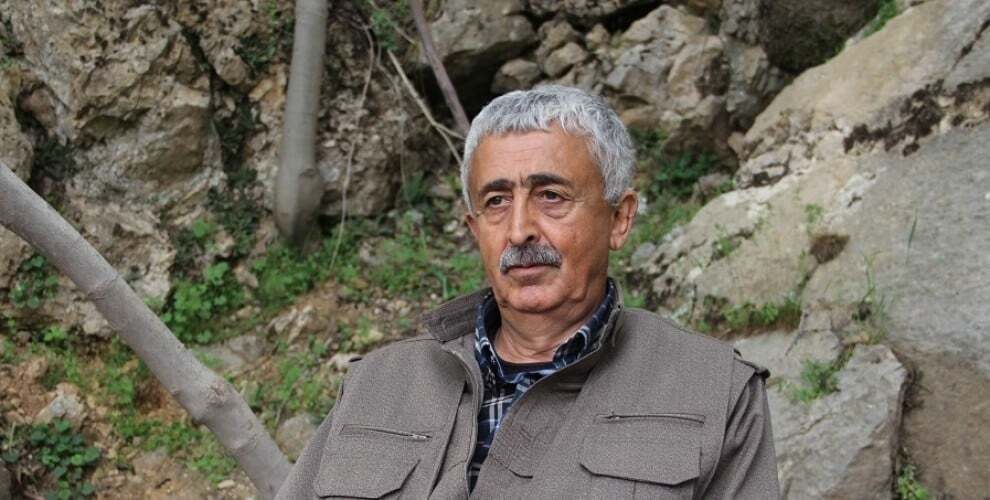

“Creating a New Society in the Here and Now”: An Interview with Riza Altun

In 2014, I was on my way to interview one of the founding members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, the PKK. While he was not in the small group of people who attended the organization’s founding congress on November 26–27, 1978, he had certainly played a key role in the earlier formation process of the group in Ankara, from which the PKK would eventually emerge. When the car stopped in front of a house somewhere in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, I instantly recognized the man who came out to greet me. It turned out that I was going to interview Rıza Altun.

At the start of the interview, Altun was more eager to discuss the so-called Islamic State, which at the time was stringing together victory after victory. The group was facing fierce resistance from the PKK, whose fighters were standing their ground rather than fleeing. After a long conversation about the roots of ISIS’ rise, the political collapse and violent sectarianism that followed the U.S. occupation of Iraq, our discussion turned to the late 1970s.

In 1975, the year he turned 19, Altun was living in Ankara’s Tuzluçayır neighborhood when he first encountered the early cadres of what would become the PKK. He eventually joined them, remaining a leading figure in the organization for decades—until he was seriously wounded in a Turkish military attack on March 21, 2019. After a second assault, he succumbed to his injuries and died on September 25 of the same year. His death was officially confirmed at the PKK’s 12th Congress in 2025

Can you tell us about the formation of the PKK and how you became involved?

…the Kurds were in a colonial situation, and their struggle for freedom and right to self-determination was central

Our movement began to take shape in the 1970s. At that time, the pioneering cadres who would go on to form the movement were each involved in various leftist circles. In this period, Turkey had a vibrant and diverse leftist landscape, rich in ideological debate, action, and organizational activity. After 1972, the Kurdish issue began to gain prominence. Yet, the dominant view among the classical left was that once the socialist revolution occurred, all people—Turks and Kurds alike —would automatically become free and equal. It was a simplistic, yet at the time, widely shared viewpoint within the left. Some of us, from different leftist backgrounds, began to question this logic and discuss the Kurdish issue more directly. This was a foundational moment for our movement.

The history of the PKK thus began with a rethinking of the Kurdish question within leftist politics in Turkey. It signaled the beginning of a new approach. Rather than assuming that freedom would come after a revolution, we believed that genuine freedom could only be achieved by confronting and resolving the deep-rooted social contradictions in Turkey. This led us to a crucial observation: the Kurds were in a colonial situation, and their struggle for freedom and right to self-determination was central.

So, in parallel, we were opposing both dogmatic leftism and narrow nationalism

Another key point of divergence with the left lay in how it oriented itself ideologically. Much of the left was imitative of the Soviet Union, China, or Albania. This “copycat” leftism lacked originality and failed to inspire hope for revolutionary change. Our rejection of this imitative leftism was also critical to the formation of our movement.

Alongside these limitations within the left, we also faced the challenges of nationalism in Kurdistan. Much of it was reformist on the surface, but beneath it was a deep aspiration for a nation-state. We called this “primitive nationalism”, and we consciously distanced ourselves from it. So, in parallel, we were opposing both dogmatic leftism and narrow nationalism.

What began as a group of friends discussing the left, Kurdish nationalism, and the Kurdish question gradually developed into a political movement. When we decided to actively engage in struggle within Kurdistan, the movement transformed into something larger—a political and organizational force that inspired hope. For many who had lost faith in alternatives, our movement became a new path forward. Even if people were not fully aware of its ideological depth, many gravitated toward the party. In 1973, we were just a small group of friends. By the 1980s, we had become one of the most influential movements in Kurdistan, building considerable momentum. However, this also brought challenges. While colonialism was the primary target, we also had to defend ourselves from attacks by traditional leftist groups and nationalist factions.

In short, you could say the PKK was born out of three key struggles: against a dogmatic leftism shaped by real socialism, against nationalist currents in Kurdistan, and against colonialism itself.

How did you personally get involved with this movement? When did this happen?

Our family is originally Kurdish, from Dêrsim. But we were exiled—from Dêrsim to Kayseri. No one in the family knows exactly when or why. Eventually, they settled in a small town called Sarız in Kayseri. Then, in the 1960s, we moved to Ankara.

The neighborhood in Ankara that we moved into, Tuzluçayır, had a strong leftist leaning. It was in this environment that I began participating in leftist associations. Around 1975, we started hearing rumors about a group called the Apocular[1]. Most of what we heard was negative. They were portrayed like the Nationalist Movement Party, the MHP, in Turkey—nationalist and fascist, but with a focus on Kurdish identity. People described them as aggressive, always fighting, and hard to talk to—reckless and undisciplined.

Then I met Kemal Pir and other comrades in 1975. Once I actually got to know them, I realized how false those portrayals were. They weren’t nationalists like the MHP. On the contrary, they were a leftist, socialist movement that strongly advocated Kurdish freedom, including the right to self-determination. We immediately felt a deep sense of affinity.

How did you meet Kemal Pir?

It happened by chance. Our neighborhood was a hub for revolutionary activity, home to all kinds of leftist groups. Kemal came to the neighborhood, and that’s where I met him[2]. At first, I couldn’t quite make out his political stance. He stayed in the neighborhood for almost a year, constantly offering critiques—of the Turkish left and nationalism—but without clearly proposing an alternative. He wasn’t saying much about the Kurdish issue either.

Then he disappeared for about five or six months. When he returned, he asked me to meet and discuss some things. During that meeting, something felt different. He started with a broad evaluation of Turkey’s political situation and then raised the Kurdish question directly. He spoke openly about the Kurdish people’s right to self-determination and the need to build a revolutionary movement in Kurdistan.

Our family never hid its Kurdish identity. Because we were Kurdish ourselves, Kemal encouraged us to take a deeper interest. That conversation sparked genuine excitement in us. Still, at that point, we didn’t really know who Kemal Pir was. A few days later, he said, “I’ll introduce you to some comrades.” That’s how we met Abdullah Öcalan, Haki Karer, and Duran Kalkan. From late 1975 onward, they began regularly visiting our home. That’s when we officially became part of the movement—during its early group formation phase. Alongside a group of neighborhood friends, I joined.

And before you met them in 1975, how were you involved in politics?

Tuzluçayır was a poor, mostly Alevi neighborhood with a strong leftist culture. After the March 12th, 1971 military coup d’état and the execution of Deniz Gezmiş and his comrades, a wave of revolutionary sentiment swept through the area. I strongly leaned toward the political current associated with Deniz Gezmiş. We formed a local group, though our involvement was more sympathetic than ideologically structured. Still, we were active—distributing pamphlets, putting up posters, clashing in the streets with fascist MHP supporters, and later organizing neighborhood committees. We did all of this under the banner of the People’s Liberation Army of Turkey (THKO). I was getting increasingly involved.

How did you organize?

Unlike both Turkish nationalist and Kurdish nationalist histories—which often glorify resistance and heroism—this movement approached history critically

While most leftist and Kurdish movements had journals and formal associations, we operated differently. Our structure was based on regular meetings and educational groups in people’s homes.

After joining the movement, Kemal Pir would regularly visit our home for discussions. Abdullah Öcalan also visited often. They critiqued dogmatic socialism, the Turkish left, and Kurdish nationalism, offering clear distinctions between themselves and these other ideologies. They introduced us to new interpretations of the social and historical dynamics of both Turkey and Kurdistan—ones we had never encountered before.

Unlike both Turkish nationalist and Kurdish nationalist histories—which often glorify resistance and heroism—this movement approached history critically. For example, if the Ottomans were so powerful, as the Turkish nationalists said, how did they end up as a small, defeated nation-state? That’s not a story of triumph—it’s one of failure. Similarly, if the Kurds have always resisted, how did they become a colonized people, on the brink of forgetting their own language?

We avoided the typical routes of organizing through associations or publications. These platforms were too vulnerable to state infiltration and repression.

Neither Turkish nor Kurdish nationalist narratives offered compelling or realistic understandings of history. Instead of romanticizing past resistance or assigning heroic meaning to every event, the movement emphasized the importance of critique—of recognizing historical shortcomings and learning from them. It was a new way of understanding history: not as a list of glorified moments, but as a field of analysis to be studied, questioned, and learned from. That historical perspective profoundly shaped us. It gave us an entirely new lens through which to view our identity and our struggle.

The educational meetings gave the group its ideological, political, and organizational foundation—one that gradually developed in a way that diverged from the norms of the time. We avoided the typical routes of organizing through associations or publications. These platforms were too vulnerable to state infiltration and repression. That vulnerability, in fact, was one of the major reasons the Turkish left failed to sustain itself. You simply cannot build a revolutionary movement from such open and loosely defined spaces. Of course, associations have a role in civil society—but that’s something different. They cannot serve as the foundational base for a revolutionary movement.

At the time, I didn’t fully understand this. We used to ask, “Why don’t we have a journal? Why no association? We have plenty of contacts in the neighborhood.” The answer was always: “There’s no need. Let’s not rush. Maybe later.” Instead, the focus was on small, home-based educational sessions. And it worked. It worked very well. It began with modest face-to-face meetings in homes and evolved into a complex, multifaceted educational model. That model has remained central to the movement’s unity, ideology, and identity.

One key element is personality analysis, which is very difficult and, frankly, frightening

When we speak about education, we’re not referring to simply reading books that say: “This happened in year X, freedom means Y, socialism means Z.” It doesn’t work like that. At the heart of our educational model is something we call mentality—a concept we’ve built much of our education around. One key element is personality analysis, which is very difficult and, frankly, frightening. It forces people to confront their own social reality, their historical truth, and see themselves clearly within the forces that have shaped them. That’s a terrifying thing to do—for anyone.

Take many egalitarian, communal, or leftist movements—they constantly use concepts like equality, often in very utopian terms. The language sounds progressive. But when you examine their actual lives, they are deeply individualistic, completely capitalist, even. In other words, there’s a wide gap between what is said and what is lived.

So, the question is: Will your life be guided by what you say, or by what you do? Because what you live is your reality—not your thoughts. Sure, thoughts matter. They have value. But life is what’s actually lived. As long as there is a contradiction between one’s ideas and one’s actions, what will that contradiction produce? Where will it take us? What kind of person—or society—does it create?

That’s the power of the PKK. It creates society.

When we talk about mentality, we mean identifying what must be rejected—intellectually and practically—by questioning ourselves. And beyond that, we aim to begin living what we hope to create, starting not ow. That means forging a powerful dialectic between thought and action. To say “This is the revolution of the future” but postpone living it until some distant point—that’s a guarantee you’ll never get there. But if you start living your values today, you begin to create a new society in the here and now. That’s the power of the PKK. It creates society.

Endnotes:

[1] “Apoists”, after Abdullah Öcalan’s nickname Apo.

[2] In another interview, Rıza Altun explained that there were two main channels through which one could become involved in leftist politics in Tuzluçayır: an association established in the neighborhood and the leftist coffeehouses frequented by local youth. Kemal Pir visited both the association and the coffeehouses, but since everyone in the neighborhood knew each other, it was difficult for outsiders to blend in. It took some time before he was able to earn their trust. See: https://firatnews.com/guncel/apocularin-mahallesi-tuzlucayir-212615

Joost Jongerden

Joost Jongerden (PhD) is an Associate Professor of Rural Sociology at Wageningen University, the Netherlands. His research focuses on forced migration, rural development, and political and violent conflict in the Kurdistan region, with particular attention to dispossession, displacement, and how people actively pursue alternative futures—an approach he describes as Do-it-Yourself Development.