Who Wants “Middle Eastern” Books?

The 2023 satirical film American Fiction will make you laugh out loud, but often, you are laughing at the absurdity of a racist system.

Based on Percival Everett’s novel Erasure, American Fiction spotlights the publishing industry’s hypocrisy and gatekeeping that decides which novels are deemed “authentic” or “sellable”. For many non-white authors and publishing professionals, the film reflects a not-so-often talked about hierarchy. Among them, Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA) writers, routinely encounter narrow expectations about what constitutes a “Middle Eastern” story.

To understand how these dynamics play out behind the scenes, The Amargi spoke with three publishing insiders: literary agent Abi Fellows, author Ava Homa, and co-founder and editor of Afsana Press Goran Baba Ali.

Who Gets Published?

Literature is incredibly subjective, and what some consider a good novel, others might see as downright bad. Literary agent Abi Fellows said she has a few criteria for the books she wants to represent: an original voice, writing quality, and a degree of marketability – or how well readers might respond to the story. Additionally, Fellows mentioned seeking out underrepresented voices.

there have been instances when editors have asked authors she represents to tone down cultural elements in their stories, in order to appeal to a wider audience

Often, these underrepresented voices are authors of color, whom, according to Fellows, the industry marginalizes. For example, in the United States, white people dominate the publishing industry, with 95% of writers and staff being white.

There also seems to be a degree of intentionality in keeping the industry white, as Fellows stated there have been instances when editors have asked authors she represents to tone down cultural elements in their stories, in order to appeal to a wider audience – something which she staunchly disagrees with and works to help her authors avoid.

Ava Homa, whose work often interrogates how power shapes narrative and visibility, pointed out that she had also received such requests from editors. Homa referenced one of Rumi’s parables from Masnavi Manavi in talking about the subject. In the parable, an innkeeper, adamant on making sure all his guests fit their beds, takes drastic measures: “If people are too tall, he [the innkeeper] would try to cut their legs to fit the bed, and if they are too short he would try to stretch them,” Homa said, noting, the innkeeper’s absurd logic. She compared the innkeeper to the publishing industry, and how the industry cuts and trims everyone to make them fit preconceived notions and cultural expectations.

Investigations into the publishing industry have shown that these issues are persistent largely because they are systemic. As PEN America’s report shows, the overwhelming lack of diversity within the industry is a critical factor in why non-white stories have a hard time getting published.

As the report shows, within culture-focused industries like publishing, where subjective interpretation decides what is “good literature” and what is “bad”, the industry’s cultural makeup becomes “a major determinant of what gets published”, hence “the whiteness of the industry’s staff has accompanied a largely white cadre of published authors.”

When I asked Homa if SWANA authors and stories are pigeonholed, her immediate reaction was laughter, “That’s a rhetorical question, right?”

To varying degrees, this trend is present in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Talking about the UK, Fellows said that in part this is because the industry caters to an audience that is more familiar with narratives centering Western stories, and when it comes to all others, “There is more focus on finding the one, exceptional story to represent a part of the world,” rather than publishing many books, which would address the cultural and historic nuances of a region that is as diverse as SWANA.

What then often happens is that SWANA representation, along with that of many other non-white populations, is essentialized, and nuance is thrown out the window. The

Middle East Is a Genre

When I asked Homa if SWANA authors and stories are pigeonholed, her immediate reaction was laughter, “That’s a rhetorical question, right?”

Homa described the essentialized outlook many have about writers from this part of the world: “You’re expected to produce suffering without complexity, without nuance, beauty, love, or joy.” And she added that when an author writes stories where female characters from SWANA have critical thinking skills and are outspoken, “They don’t know what to do with you. They ask ‘Who are you? You’re not who you’re supposed to be.’”

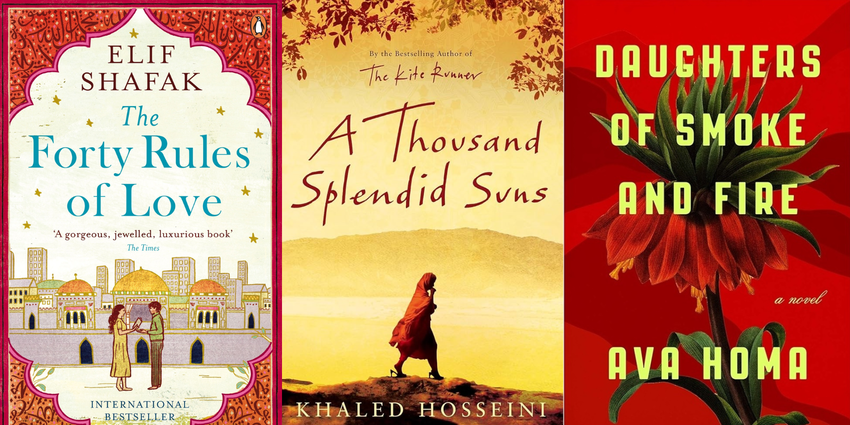

When Homa sold her own novel, Daughters of Smoke and Fire, the pigeonholing began from the get-go, with one graphic artist wanting to put an image of a hijabi woman on the cover, all because the story takes place in Kurdistan and Iran – Homa, naturally, rejected the idea, noting that the assumption reduced a complex story about gender, choice, and freedom into a single visual shorthand that contradicted the essence of her novel.

However, both Homa and Fellows emphasized that within publishing, there is a difference between independent publishers and corporate publishers, at least in terms of which types of stories are platformed. Afsana Press’s list of published books is a testament to this.

Afsana’s editor, Goran Baba Ali, said they did not establish the publishing house with the intention of giving space to underrepresented voices; they search for good literature anywhere they can find it and give equal opportunity. By comparison, corporate publishers try to predict what readers want, which ends up “shaping the market and the audience,” Goran said, which steers audiences’ taste and can often reinforce familiar – and harmful – narratives.

But the silver lining is that there are signs of change: both Goran Baba Ali and Abi Fellows pointed out that what they have noticed over the last few years is audiences gravitating toward new topics, cultures, and new takes on familiar genres.

This could, in theory, lead to a larger opening for SWANA authors and stories. This is already having a real-world impact, as Afsana Press’s latest published work, a translation of Bachtyar Ali’s The Last Pomegranate Tree, was widely publicized and created a buzz of excitement that is not commonly seen for translated SWANA novels.

no one would think it right to group Polish novels and Spanish novels together as generic “European” literature; why then is it such common practice to do that to literature from Kurdistan and Turkey and Egypt and Tunisia and Afghanistan?

However, it does not help that almost all literature with a connection to SWANA is categorized as a single genre. Goran Baba Ali pointed to this issue specifically and emphasized their efforts to avoid becoming part of this practice, which, for him, amounts to essentializing identity and culture.

It is important to highlight the absurdity of this genrefication, where a canon of literature from a region as large and populous as a continent is categorized as one genre. After all, no one would think it right to group Polish novels and Spanish novels together as generic “European” literature; why then is it such common practice to do that to literature from Kurdistan and Turkey and Egypt and Tunisia and Afghanistan?

How Stories Shape Power

The genrefication of SWANA literature is no small grievance; there is power in representation. This is hardly a groundbreaking idea, but in the case of the publishing industry, it is especially necessary to emphasize, as literature has historically been a space of both liberation and oppression.

Power and language are interrelated concepts that support and change one another. Stuart Hall made a strong case for this in The Spectacle of the Other, in which he argues that language is essentially a collection of symbols. These symbols are objectively meaningless, but human culture attaches meaning to them through daily interactions and activities. In his column for The Amargi, writing about Syria’s new Islamist leader, author Bachtyar Ali shows this process in detail.

Literary and non-literary narratives have always been usurped by the powerful to be used as tools of domination, especially in the case of SWANA. The concept of “Middle East” illustrates this well: for two decades now, “Middle East” has been mentioned almost exclusively in association with “terrorism”. The repetition of this association has, over time, made “Middle East” and “terrorism” implicitly interconnected concepts. Terrorism has become Middle Eastern, and the Middle East alludes to terrorism.

American Fiction tackles this same issue in terms of Black American representation in the U.S., where the industry explicitly supports and repeatedly publicizes stereotypes that reduce Black American identity and history to simplistic and dehumanized representations; and art and literature that go against this essentialized outlook are often rejected by mainstream media, while literature that reinforces it is often celebrated.

Historically, this has been a key step in the process of colonial practice. This process has made it easy for hegemonic powers to brutalize the peoples of SWANA, specifically, as Ava Homa mentioned, stateless peoples who have been made twice or thrice invisible, such as Kurds, Amazighs, Baluchis, or Assyrians, among others.

The publishing industry is, of course, not the main machinery behind centuries of atrocities, but it is complicit, and especially when industry insiders say authors of color are rejected for trying to break stereotypes, there clearly is a concerted effort to protect the status quo.

Looking Forward to Change

The power to decide what stories are publishable is one that is self-reproducing; it creates a cycle that, unless directly and intentionally interrupted, only morphs and disguises itself rather than changing radically.

American Fiction spotlights the complex relationships involved in creating literature that reinforces degrading and harmful narratives, while also addressing the often-willful blindness of those who sustain them. Its existence as a story – both as a novel and as a film – shows that change, even if coming at a glacial pace, is coming nonetheless. It is also a warning: those refusing change today may no longer have a say in the industry tomorrow.

Jîl Şwanî

Jîl Şwanî is an author and editor whose work includes fiction and nonfiction books. Most recently he worked as an editor with Hamburg University Press and Bristol University Press, while his short story, The Wishing Star was published in the Comma Press’s anthology Kurdistan+100. He hosted the What Happened Last Week in Kurdistan podcast. Currently, he is writing a novel inspired by Kurdish mythology.