The Struggle and Revival of the Kurdish Language

Once whispered in secret and prohibited from even the simplest outdoor conversations, the Kurdish language has long shared the struggle of its people–enduring repression, exile, and erasure. Today, as a result of decades of struggle, it is beginning to carve out a fragile presence in the world, finding its voice in the context of new technologies. Despite such developments, Kurdish bears the weight of internal fragmentation and long-standing neglect, obstacles that continue to slow its journey toward full recognition and revival.

Oral Origins and Poetic Preservation

The Kurdish language owes its survival not to formal institutions, but, arguably, to poetry and music.

For centuries, the Kurdish language was not used in written form. Despite being the main means of communication among the Kurds, even most Kurdish intellectuals and poets preferred to write in other dominant languages, particularly Arabic and Persian. Indeed, over three centuries ago in his Mem û Zîn masterpiece, the renowned Kurdish poet Ehmedê Xanî lamented that the Kurds had become ‘orphans,’ and that the neglected Kurdish language was like ‘copper’ (in comparison to ‘gold’ like dominant languages). The same frustration was echoed by another respected Kurdish poet, Nalî, who, over a century later, became the first poet to write in Soranî Kurdish. Nalî actively encouraged others to write in Kurdish as he hailed the potential of the language.

The Kurdish language owes its survival not to formal institutions, but, arguably, to poetry and music. For centuries, it existed primarily as an oral tradition, preserved and enriched by a lineage of poets to express a wide range of human experiences. Feqiyê Teyran employed the Kurdish language for religious devotion, Mahwî for philosophical reflection, Nalî for romantic longing, and both Ehmedê Xanî and Hacî Qadirî Koyî to advance Kurdish nationalism. Through their verses, these poets shielded the language from obscurity and oblivion.

“The history of the Kurdish language is a story of life and death,” Dr. Metin Yüksel, professor at the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at Hacettepe University in Ankara, Turkey, who has extensively written about the Kurdish language, told The Amargi.

One language, four policies

Kurdish children still lack formal education in their mother tongue in Turkey, and a recent survey found that three out of four Kurdish children no longer speak their mother tongue

Following the establishment of Middle Eastern nation-states after World War I, a process which minoritized the Kurds as a people without their own state, the Kurdish language was subjected to systematic repression and forced assimilation.

During the early years of the Turkish Republic, the use of Kurdish was strictly banned across Turkey’s Kurdish regions. As the late intellectual Musa Anter recorded in his diaries, in the 1930s, anyone caught speaking Kurdish was fined one Turkish lira per word. This decree effectively silenced, for instance, the residents of Mêrdîn (Mardin), many of whom spoke only Kurdish, forcing them to resort to sign language when communicating in public. This enforced silence is powerfully echoed in Yılmaz Güney’s 1978 film The Herd, in which the character Bêrîvan becomes mute, symbolizing the broader suppression of Kurdish voices at the time.

This strict policy in Turkey persisted throughout the 20th century, and only with the rise of the Kurdish freedom movement did restrictions on the language begin to ease in the late 1990s and early 2000s. State television began broadcasting in Kurdish, private Kurdish-language schools opened, and publications in Kurdish multiplied. Yet, Kurdish children still lack formal education in their mother tongue in Turkey, and a recent survey found that three out of four Kurdish children no longer speak their mother tongue. Moreover, the state frequently resorts to banning institutions promoting the language as part of broader policies to criminalize Kurdish politics.

Similarly, in Syria, after the establishment of the French Mandate (1920–46), Kurdish demands to use and teach their language in Kurdish-majority areas were overwhelmingly rejected. Early publications such as Hawar appeared briefly, but subsequent regimes, especially the Ba’ath Party, pursued aggressive Arabization policies and forced displacement. Any limited tolerance of Kurdish culture proved to be tactical, not genuine.

It was only after 2011 that the Syrian Kurds, together with the other communities in the Northeast, succeeded in forming a de facto autonomous administration. For the first time in the country’s history, Kurdish children were educated in their mother tongue, and Kurdish itself became one official language within that administration. Nevertheless, the central government in Damascus still refused to recognize Kurdish as an official language at the national level.

The struggle for the Kurdish language varies across different parts of Kurdistan. While the suppression has historically been more severe in Turkey and Syria, the language was somewhat tolerated in Iraq and Iran. This explains the relatively greater advancement of the Soranî dialect compared to Kurmancî, despite the latter having far more speakers.

Except for the short-lived Republic of Kurdistan in Mahabad (1945–1946), which made Kurdish an official language, Kurdish has never enjoyed official status or meaningful recognition in Iran. Under Reza Pahlavi (1925–1941), the Kurdish language was banned, adding to the Kurds’ marginalization as both an ethnic and religious minority in a Shi’a-majority country. His successor, Mohammad Pahlavi (1941–1979), slightly relaxed these restrictions by permitting limited Kurdish publications and broadcasts.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Article 15 of the constitution appeared to support minority languages in the media and education. Yet, in practice, the state frames such efforts as security threats, frequently arresting Kurdish language teachers and activists, such as Zahra Mohammadi, who was sentenced to five years in prison for teaching Kurdish in 2022. Nevertheless, the establishment of the Kurdish Studies Research Institute at the University of Kurdistan in Sanandaj (Sine), Iran, in 2000 marked a great step in scientific research on the Kurdish language, both within Iran and beyond.

Compared to neighboring states, Kurds in Iraq have long enjoyed a comparatively favorable linguistic environment. After the Ottoman Empire’s collapse in 1918, the British mandate oversaw the creation of modern Iraq. In 1919, the city of Silêmanî (Sulaymaniyah) saw the first Kurdish printing press, with British authorities even encouraging Kurdish as a written language. Throughout the 1920s, several Kurdish newspapers sprang up, though their fortunes rose and fell with shifting relations between Iraqi rulers and Kurdish communities.

In 1959, the University of Baghdad established a Kurdish Studies department, sparking a short literary revival before repression returned. In 1970, Kurdish became Iraq’s second official language; that same year, the Kurdish Academy of Sciences opened in Baghdad, and many Kurdish journals appeared. These milestones gave the language a major boost.

The 1991 uprising and resulting establishment of the autonomous Kurdistan Region brought further gains: education in that territory became exclusively Kurdish-medium, as cultural life flourished. Finally, after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, the 2005 Iraqi Constitution enshrined Kurdish alongside Arabic as a state language, and, for the first time, Kurdish appeared on key national documents such as passports.

Dialectal Divides

Besides facing political repression, Kurdish speakers are also hindered by internal divisions.

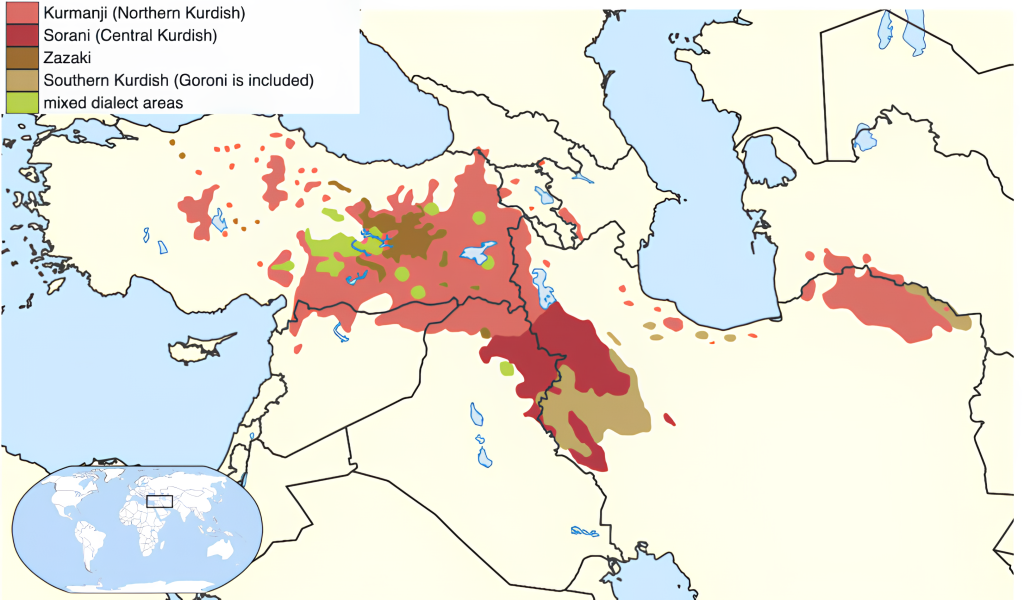

According to the Kurdish pioneer linguistic scholar, Prof. Amir Hassanpour, Kurdish comprises at least four geographic dialect groups, often referred to as the Northern, Central, and Southern varieties, which coexisted without hierarchy before the twentieth century. Hassanpour argued that in pre‑nationalist Kurdistan, linguistic and literary diversity was the norm in a largely rural, feudal society, and dialect differences did not impede a shared sense of Kurdish identity. Kurmancî and Hawramî both developed literary traditions in the sixteenth century, followed by Soranî in the nineteenth.

Soranî and Kurmancî are the most spoken dialects of Kurdish, each reflecting distinct local histories and the complex regional politics. Kurmancî, or Northern Kurdish, is the older written form. Manuscripts dating to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were produced by poets such as Ehmedê Xanî and Melayê Cizîrî. Today, around eighty percent of the world’s thirty to forty million Kurdish speakers use Kurmancî across south-eastern Turkey, northern Syria, and the borderlands of Iraq and Iran. Soranî, or Central Kurdish, emerged as a literary language in the nineteenth century under the patronage of the poet Nalî and has since received more institutional support, particularly in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Despite their shared roots, Soranî and Kurmancî exhibit some differences in everyday vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammar. One study comparing the 500 most common Kurmancî words with their Soranî equivalents identified 49 distinct items, many among pronouns and other high-frequency words.

“Creating a new language by merging two dialects, or imposing one on the others, is misguided and bound to fail”

Aso Mahmoodi, co-founder of Vejin

The differences between the dialects have often been taken as an occasion for policies to dive and rule populations. In the early 1930s, the Iraqi government exploited the differences between Kurmancî and Soranî to refuse the recognition of Kurdish as an official local language. Since then, various initiatives have sought to unify the language, either by developing a single standard form or by designating one dialect as the official tongue. In his memoirs, the Kurdish writer and poet Cigerxwîn, himself a native Kurmancî speaker, describes the fierce debates at the Kurdish Teachers’ Congress in Sheqlawe in 1959 and 1960 over which dialect should be chosen as the standard.

Unlike in the Arabic-speaking world, where Modern Standard Arabic provides a uniform literary form for use in media, education and official discourse, Kurdish has no equivalent standard format. In Arabic, speakers from the Levant, the Gulf, and North Africa can, despite great cultural and geographic distances, switch to Modern Standard Arabic when reading newspapers, watching pan‑Arab television, or attending university. This allows them to communicate despite very different regional dialects. By contrast, neither Soranî, nor Kurmancî can serves as a pan‑Kurdish standard. This absence of a single, formal register limits cohesion in education, broadcasting, and official communication across Kurdish‑speaking regions.

“Creating a new language by merging two dialects, or imposing one on the others, is misguided and bound to fail,” says Aso Mahmoodi, co-founder of Vejin, the largest Kurdish online dictionary and literary corpus. He told The Amargi that the priority should be standardizing written forms, orthography, spelling, and punctuation within each dialect while remaining mindful of other Kurdish varieties. Likewise, Dr. Metin Yüksel, a speaker of both dialects, sees this diversity as a strength. He suggests that bringing the dialects closer together depends on language policy in the Kurdistan Regional Government, where Kurdish holds official status.

One of the most significant obstacles between dialects is their use of different writing systems. Kurmancî employs a Latin-based alphabet, while Soranî uses an Arabic-based script. This division means that a speaker of one dialect is often unable to read texts in the other.

Mahmoodi, who holds a degree in computational linguistics, has developed an open-source tool that converts accurately between the Kurdish scripts with only minimal errors. He is urging web developers to integrate this converter into Kurdish-language sites. “Above all, each dialect should adopt a unified orthography that respects its own norms while remaining readable for speakers of other Kurdish varieties,” he says.

Kurdish in times of AI

Despite significant political and internal obstacles, Kurdish is gradually securing a place for itself–now also in the digital world and within artificial intelligence models. In a major milestone, Kurmancî was added to Google Translate in 2016, followed by Soranî in 2022. Since 2023, Meta has been working to integrate both dialects into Facebook. To date, more than 2.3 million words have been translated, allowing users to navigate the widespread platform in Kurdish.

Kurdish also appears in popular AI models such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude, although accuracy remains inconsistent. At times, the output contains enough errors to distort meaning and hinder comprehension. Yet, for many, the mere presence of Kurdish text suggests progress.

…although there is already enough Central Kurdish material online to build a solid model, the overall standard of the texts is relatively low

Kurdish language advocate Sarchia Khursheed describes Kurdish as a “low-resource” language on public domains–for instance, the relative scarcity of online articles, documents, and books delayed Soranî’s inclusion in Google Translate. Recent advances in model efficiency and a rise in digital data in Kurdish finally made that step possible. Khursheed adds that some large language models still struggle with Kurdish because they have had little high-quality material to learn from. By contrast, newer systems such as Google Gemini show that, with sufficient data, models can write in Kurdish in ways that are almost indistinguishably from native authors. This demonstrates that existing online resources can support robust models if companies choose to invest in low-resource languages.

While the volume of digital texts is crucial for training linguistic models, the quality of the material matters. Mahmoodi points out that although there is already enough Central Kurdish material online to build a solid model, the overall standard of the texts is relatively low. He attributes this to the absence of a unified orthography, multiple keyboard layouts, inconsistent spelling, and a general disregard for orthographic accuracy among writers. “I have noticed that the same Kurdish author can produce a paragraph in Kurdish containing more than ten spelling and punctuation errors, but rarely make mistakes when writing in Persian,” he says.

To address these challenges, Mahmoodi has founded AsoSoft. The platform aims to elevate the quality of Kurdish texts by enforcing consistent standards of spelling and punctuation, thereby strengthening the foundation for future AI applications.

Milestones in the Kurdish Language:

- 16th century: Melayê Cizîrî composes the earliest known Kurdish literary work

- 1898: First Kurdish newspaper appears in Cairo

- 1915: Husên Huznî Mukriyânî establishes the first Kurdish press in Aleppo

- 2005: Kurdish is enshrined as an official language in Iraq

Endangerment and the Path Ahead

With recent advances and a growing revival of Kurdish, it may seem odd to ask whether the language remains endangered. Although the two dominant dialects are not classified as being at risk, a couple of Kurdish subdialects do appear on UNESCO’s list of endangered languages. In the 2010 Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, Zazakî/Dimilkî, with 1.5 million native speakers, was classified as vulnerable. Hawramî, spoken by around 300,000 people, was listed as definitely endangered.

A comprehensive 2021 study warns that, without intervention, more than 1,500 languages will be lost by the end of the century, including these two Kurdish dialects. It predicts that language loss could triple within 40 years, with at least one language disappearing each month. The authors call for urgent investment in language documentation, bilingual education, and community-based preservation programs.

“Anyone observing Kurdish communities in Turkey will notice that children born to Kurdish-speaking parents today often neither speak nor understand the language,” says Dr Metin Yüksel. This decline, he argues, places Kurdish at existential risk in Turkey, where the largest Kurdish population resides. One of the main demands of pro-Kurdish parties in Turkey is to promote the language in schools across Kurdish-populated areas and to make it a medium of instruction rather than an optional class.

Aso Mahmoodi argues that Kurdish also faces a gradual, dialect-by-dialect shift towards Arabic, Persian, Turkish, or English. “As children are educated in those languages, they internalize their grammatical systems. Over time, their vocabulary and sentence structures evolve into what can no longer be called Kurdish. Before long, many elders will not be able to understand their grandchildren.”

A more recent and subtle internal pressure on Kurdish comes from the rising prestige of English as the gateway to employment and modern mobility, especially in private schools and universities where English-medium instruction is marketed as the ticket to a secure future. Students and families increasingly prioritize English because it is seen as the language of opportunity. This instrumental shift is reinforced at home: parents, motivated by economic aspirations, often channel children into English-dominant environments, weakening intergenerational transmission of Kurdish, and accelerating language loss, a pattern captured in family language policy research and various studies among Kurds in Iraq. Scholars warn that this dynamic, layered atop existing marginalization, turns English into not just a competing tongue but a contributor to the gradual sidelining of Kurdish in public and private domains.

Much remains to be done to maintain linguistic diversity in Kurdistan. Yet, even speakers of the dominant varieties of the Kurdish language should not be complacent. Some scholars point out that no language is eternal–one day, even English could disappear. Subjects of the Roman or Egyptian empires may have believed their languages would live forever. But even empires fall.

Renwar Najm

Renwar Najm is an Iraqi Kurdish journalist with a career that began in the early 2010s at the esteemed Awene newspaper. He holds a master’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of Kent and Philipps University of Marburg.