Seher: The Invisible Woman

In 1962, James Baldwin wrote that it is necessary to approach those who oppress us with love and acceptance, but, knowing the gravity of those words, he emphasized that acceptance is not synonymous with submission. For Baldwin, it was essential to acknowledge that the oppressor, too, is in need of liberation. Otherwise, neither the oppressor nor the oppressed can be free.

This perspective mirrors that of Boaventura de Sousa Santos, whose work on domination and liberation arrives at similar conclusions. In de Sousa Santos’ view, the world is divided into two, and this division is because of what he calls the “abyssal line”. Both sides of this division experience domination, albeit in very different ways. Simply put, one side, the “colonial side”, is oppressed, disenfranchised, and dehumanized, while the other, the “metropolitan side”, is controlled through economic and political tools.

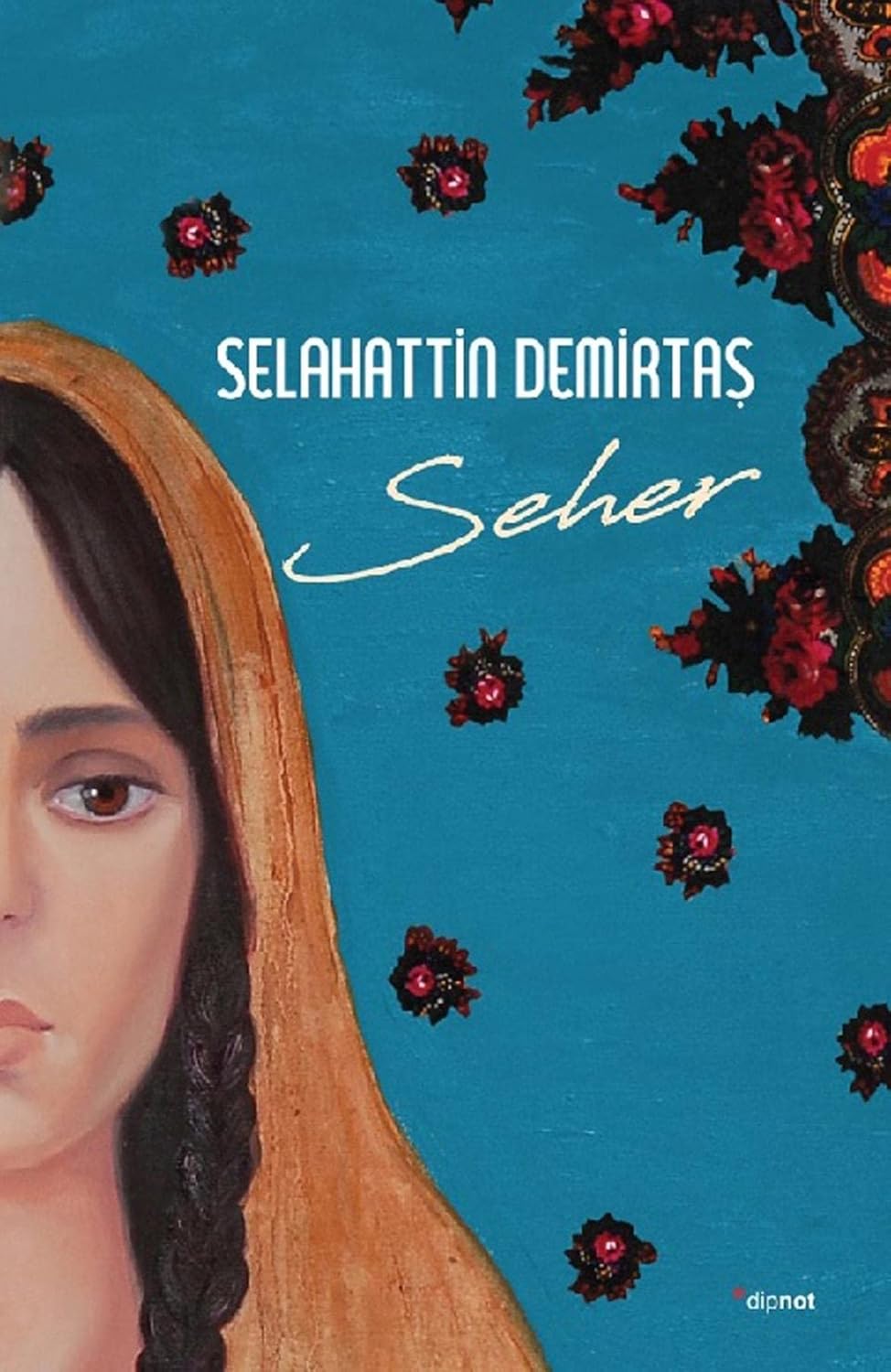

Selahattin Demirtaş, a Kurdish politician and former co-chair of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), brought this manner of domination to the forefront in Seher (Dawn), a collection of short stories that he wrote from his prison cell in Turkey. The ideas that underline the collection present the reader with the everyday lived realities of domination – realities which reflect Baldwin’s ideas regarding the liberation of the oppressor and the oppressed. The story that gives Demirtaş’s book its title, Seher, is emblematic of this perspective.

The story of Seher, a young woman living in Adana, is tragic. Three men sexually assault her, then three other men murder her. The former three are strangers, while the latter are her father and brothers. The tragic story is one worth telling, but Demirtaş’s narrative choices in the story are what make it shine.

One of these vital choices is the setting: Adana, a city that has been shaped by just about every community in the wider region, and which now has a population that includes Kurds, Turks, and Arabs, among others. The choice of name for the main character is also worth highlighting: Seher, while originating in Arabic, is commonly used by all three communities. Seher could be Kurdish; Seher could be Turkish; Seher could be Arab.

…sewn into the story are fragments of Kurdistan’s oppressed reality

This intentional ambiguity is the bedrock upon which Demirtaş builds his argument, which departs from many conventions of Kurdish political literature. In Seher, focus shifts away from traditional Kurdish narratives: no uniquely Kurdish symbolism steals the limelight, nor is there a cry of nationalist fervor mythologizing Kurdishness. All there is is a young woman in love, a traditional family, and a murder. But sewn into the story are fragments of Kurdistan’s oppressed reality and Demirtaş’s counterargument against a narrative that has dominated a century of Kurdish existence.

To parse the fragments, it helps to read Seher within the context of the Turkish nationalist state rhetoric: Since the foundation of the Turkish Republic, Kurds posed a contradiction for the dominant state ideology and nationalist imagination. Kurds, at once, exist and do not exist. Mustafa Kemal, the founder of the Turkish Republic, and his ilk labeled the Kurds a backwards people. Borrowing from the European imperial playbook, he remodeled Orientalism for Turkey and produced a nationalist ideology that banned the existence of a people. They remade Kurds as “the Other”, and the state tolerated Kurdish existence only when it could be used to demonstrate Kurdish inferiority.

The state hammered anti-Kurdish propaganda so deeply into the national consciousness that Kurdishness began to run through the veins of Turkish existence.

The state hammered anti-Kurdish propaganda so deeply into the national consciousness that Kurdishness began to run through the veins of Turkish existence. Through its education system, media apparatus, and cultural institutions, the state explicitly and implicitly communicated to its population that the people of the East are unruly, tribal, and backward; women have no freedom there, and it is common for young girls to end up like Seher. This divisive rhetoric normalized the suffering of the “Other”, “over there”: it is part of who they are, and who they are is why they suffer. Kurds became the invisible “Other”, yet everyone knew who they were.

Seen from this perspective, the story of Seher, a girl murdered by her relatives to preserve “the family honor”, could be a brilliant piece of anti-Kurdish propaganda.

There is only one problem… Seher is not Kurdish. Seher is Seher from Adana.

So, what happens when so-called honor-killings – feminicides – happen in places where Kurds live next to Turks and Arabs, like Adana? What happens when the family that kills its child speaks not a word of Kurdish, like Seher’s family? What happens when Seher is not Kurdish?

Demirtaş never reveals Seher’s cultural identity. The monstrous cruelty that the men inflict on Seher is not Kurdish, Turkish, or Arab; it could be any or none or all of them. Demirtaş does not focus on identity because it is, in fact, not important. What is important in this story is the patriarchal violence against Seher.

Seher herself ruptures the division along the abyssal line: she is sympathetic, kind, thoughtful; she is a modern working woman who goes on a date and has a say in who she marries. She fits the image of womanhood of the modern Turkish Republic. But she is also from a traditional family, one that is willing to kill its children to “protect its honor”. And Seher’s siblings have names that any Kurd, Arab, or Turk in the Republic could have.

Seher sits at the intersection of both patriarchal and colonial domination

Seher sits at the intersection of both patriarchal and colonial domination. According to the Turkish state’s nationalist mentality, if Seher is Kurdish, only the tragic half of her story must be known – to demonstrate the inferiority of Kurdish culture. But if Seher is Turkish, then only the side of her that works and makes choices and fits the modern image of womanhood must be known – to amplify the image of the free Turkish woman and the superiority of Turkish culture. Either way, one half of Seher must be hidden.

Here, by removing ethnic and cultural associations, Demirtaş brings to the fore the story’s perspective on liberation and domination, one which aligns with de Sousa Santos’s view: the interplay between colonial and patriarchal dominations, which is a core dynamic in division by abyssal lines. And through this, it spotlights how colonial domination strengthens patriarchal domination and how both the Kurd and the Turk remain bound to the system of domination – both oppressor and oppressed tied up, as Baldwin has argued.

The case of Jîna Amînî, the young Kurdish woman who was killed in detention by the Iranian “morality police”, is a real-life example of the politics of nationalist discourses around feminicide. Jîna was Kurdish, and her experiences as a Kurdish woman were always ignored – that is, until her death, when she became a symbol of the Islamic Regime’s tyranny against women. At the point of her death, Persian opponents of the government made Jîna Iranian; they mourned and immortalized her by her official Persian name, “Mahsa”. Her Kurdishness was erased or, at best, considered an afterthought.

Seher defies this logic. Seher’s tragedy culminates in her murder in Çukorova, a region that is a mosaic of cultures. Through the specific choices of setting and cultural ambiguity, Demirtaş highlights the dividing abyssal line, which humanizes or dehumanizes Seher based on the side of the line she would fall on. He rejects the mentality that would frame Turkish Seher’s story along nationalist and exclusionary frameworks, as Mahsa’s death was framed. And he spotlights the system of domination that normalizes Kurdish Seher’s suffering and makes her invisible because of her identity, as Jîna was made invisible.

While Seher does not practice any kind of revolutionary agency within the story, as she submits to her family and accepts her death for the sake of “honor”, her story does serve to present the issue in a succinct manner. And therein lies the point: in the absence of identity markers, what remains is the problem at hand, which is violent domination. It shows that Kurdish liberation is tied to both gender equality and the liberation of Kurdistan and the wider region from the clutches of ultra-nationalist, colonial, and patriarchal domination.

Seher offers a different approach to liberation within Kurdish literature. Where once nationalism dominated Kurdish self-expression, for some time now new approaches have been on the horizon that attempt to widen the scope of liberation and its understanding. As Baldwin wrote, the oppressors “are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.” The oppressed can become free not by replacing the oppressors, but by freeing them, too. Turkish Seher will perish as Kurdish Seher, unless the entire system of domination is dismantled.

Jîl Şwanî

Jîl Şwanî is an author and editor whose work includes fiction and nonfiction books. Most recently he worked as an editor with Hamburg University Press and Bristol University Press, while his short story, The Wishing Star was published in the Comma Press’s anthology Kurdistan+100. He hosted the What Happened Last Week in Kurdistan podcast. Currently, he is writing a novel inspired by Kurdish mythology.