The Najaf Filter and the Prime Minister’s Jammed Knot: Who Will Earn Sistani’s Trust?

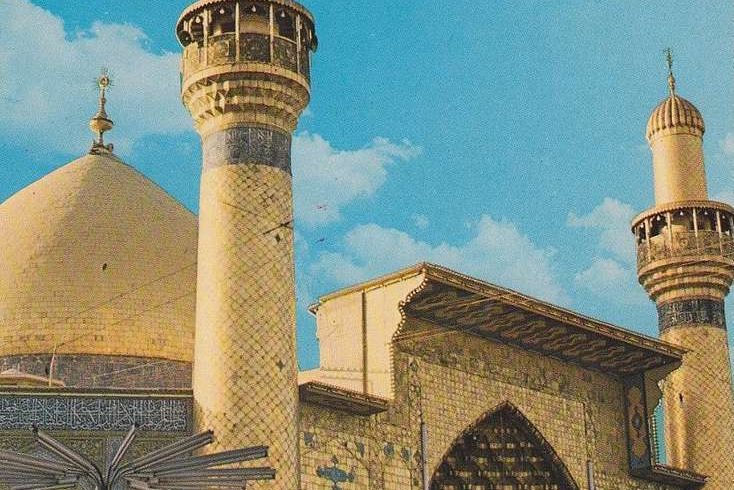

The Imam Ali Shrine in Najaf, historical center of the Marja’iyya | Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons

Following the conclusion of the Iraqi election on 11 November 2025, and the subsequent announcement of results, the Shia ranks within the “Coordination Framework” encountered complications in determining Iraq’s next Prime Minister, the Cabinet’s primary responsibility. Owing to differences of opinion and the numerous aspirants, the Shia parties have decided to resort to the religious authority of Supreme Leader Ali al-Sistani, and have him act as a mediator between them.

…however, Sistani’s office declined to accept the list with an apology. This is largely consistent with the modus operandi of the Najaf religious authority, which has maintained no direct contact with politicians since at least 2011

The “Coordination Framework” bloc (holding more than 180 seats) has reportedly prepared a list of candidates for the Prime Minister position to send to Najaf, where Sistani is based, for a decision; however, Sistani’s office declined to accept the list with an apology. This is largely consistent with the modus operandi of the Najaf religious authority, which has maintained no direct contact with politicians since at least 2011. According to various sources, the list of prime ministerial candidates includes, besides the current Prime Minister, Mohammed Shia al-Sudani and his strong rival, Nouri al-Maliki, Abdul Amir al-Shammari (Minister of Interior), Qasim al-Araji (National Security Advisor), Hamid al-Shatri (Head of the Intelligence Agency), Asaad al-Eidani (Governor of Basra), Bassem al-Badri (Head of the Integrity Commission), Abdul Hussein Abtan (former Minister of Youth and Sports), and Ali Shukri (Advisor in the Presidency of the Republic).

While the Shia supreme religious authority in Najaf, currently led by Sistani, has made it a tradition to openly intervene in politics and governance only in complicated situations, and it is opposed to religious men taking government positions and even receiving salaries from the state (in this, it differs greatly from the Iranian theory of “Wilayat al-Faqih”). However, since 2003, resorting to Najaf to resolve sensitive issues has become a traditional and common practice. From this perspective, in the jammed knot of appointing the next Prime Minister, there is a strong belief that no candidate can occupy the position without the auspices of religious authority, or at least passing through its filter, meaning that even if Sistani does not approve the candidate, he must not veto the designation. Otherwise, the candidate and the party risk facing the ire of the Shia popular base.

…the religious authority has, on other occasions, repeatedly invoked the slogan “what has already been tried should not be tried again“

After the 2014 elections, when disagreements over the prime ministerial position and other ministries reached a deadlock, Sistani, in response to a letter from the Daawa Party, prevented Nouri al-Maliki from securing a third term. In his response, the supreme religious authority stated that it would be preferable to expedite the selection of a prime minister who “has broad national acceptance” and is willing to work with other political leaders on “saving Iraq.” The letter also emphasized the need to address Iraq’s crises from a new perspective, which served as the basis for sidelining al-Maliki, even though he, as head of his coalition, had received more than 720,000 votes in Baghdad. This veto against him, now more than 10 years old, could become a point of contention in al-Maliki’s current bid for Prime Minister, who is among the strong contenders. This is especially relevant, since, in addition to this letter, the religious authority has, on other occasions, repeatedly invoked the slogan “what has already been tried should not be tried again,” emphasizing that previously appointed candidates lacking a good track record should not be tested again.

In addition to al-Maliki’s experience, the short tenure of Adil Abdul-Mahdi in 2019 is another example of the religious authority’s decisive intervention over the premiership. Following the chaos of the October protests and killings of many youths, the religious authority, on November 29, 2019, through the representative of the holy shrine in Karbala, Hani al-Sa’idi, encouraged the parliament to dissolve the government. Subsequently, Adil Abdul-Mahdi, the then-prime minister, personally submitted his resignation to the religious authority.

Today, as the Shiite bloc seeks the religious authority to resolve the issue of the prime minister and awaits Najaf’s decision, other strong, influential factors could alter their opinions and positions. These influential factors include the stance of Washington and Mark Savaya, Donald Trump’s Special Envoy to Iraq, who, through his public statements, is placing greater demands on Iraq. Additionally, Tehran’s veiled stance, implemented by its proxies and allies in Iraq, is a noteworthy factor. Moreover, the balance of power among the various lists within the Shiite Coordination Framework could play a significant role in resolving the conflict, as could the imposition of candidacy and preparations for other trials.

What is puzzling is the intensity of the competition for Iraq’s prime minister position at a time when the health of the supreme religious authority is questionable, especially given that he is over 96 years old. In recent days, visits to his home had been suspended, giving rise to rumours about Sistani’s health; but later, amid a week of questions and suspicions, it was confirmed that he was suffering from seasonal influenza, and the doors for visits have been reopened, reassuring the Shiite base to some extent.

Following recent developments in Sistani’s health, an undefined shadow looms over the upcoming government ministries in Iraq, particularly the premiership and the Shia leadership, as filling a sudden vacancy would pose a major crisis. This is because determining the Marja’ in Najaf is not like electing the Catholic Pope through a vote of a high religious council; rather, the selection of a successor passes through a complex set of mechanisms, often entailing intervention from political forces. Appointing the supreme Marja’, in addition to the usual religious conditions, relies on several other foundations, including support and acceptance from other prominent Hawza personalities; the breadth of the candidate’s popular base; and the number of followers (muqallids) on a global scale. Alongside these, other factors play a role, such as networks of relations with merchants and influential tribal leaders in central and southern Iraq, and, beyond them, Shiite political powers and forces.

…they argue that there is no legal barrier currently preventing the religious leader from issuing his opinion on issues of such importance to people’s lives

Resorting to the Marja’ in Najaf in the matter of determining the prime minister raises a fundamental question about Iraq’s constitutionally non-religious political system. In allowing a charismatic Shiite personality to gain decisive authority, potential differences with the Sunni bloc, the Kurdish bloc, and even moderate Shiite currents are ignored. This intervention also constantly revives the specter of “Wilayat al-Faqih” and religious and doctrinal dominance over the state. Those close to Sistani consistently advocate political participation during times of distress, and that the need to resolve crises among political forces is greater. Moreover, they argue that there is no legal barrier currently preventing the religious leader from issuing his opinion on issues of such importance to people’s lives.

The gatekeeper of Sistani’s house is his eldest son, Ayatollah Muhammad Reza, who, along with his brother Muhammad Baqir, serves as the ear and eye of their father, and only matters that pass through the filter of the eldest son reach their father. This advisory role of the Marja’s eldest sons is a longstanding tradition of the Najaf Marja’iyya, and the former have often served as trusted local advisors in organizational and political affairs, as well as in matters that spiritual Marja’s do not wish to address directly.

In the shadow of its Marja’iyya in the city of Najaf also resides Muqtada al-Sadr. Although he has boycotted the political process and elections, his popular base and thousands of followers lend significant weight to his opinions and stances on the issue of the prime minister. In recent years, unlike other politicians, Sistani’s door has been open to Sadr. However, regarding participation in and boycott of the elections, Sadir held an intense conversation with Sistani’s representative (Abdul-Mahdi al-Karbala’i), and later the Marja’iyya’s institutions supported the representative. Later, both entered a state of silence and stillness, and it is not clear whether this latest tension affected the coordination between Sistani’s Marja’iyya and Sadr or not, and whether both agree on the next stage of Iraq’s governance, an important factor for the stability of the future Iraqi premiership.

Yassin Taha

Yaseen Taha is a researcher and lecturer at the University of Sulaimani. He holds a PhD in the History of Islamic Orders and specializes in Iraqi affairs and the study of religious communities.