Islamists Have Lost the Kurdish Public

Kurdish protesters gather outside the UN office in Erbil, during a demonstration in support of Kurds in Syria on January 20, 2026. (Photo by Safin HAMID / AFP)

The mass Kurdish demonstrations of the last few weeks, which began as a reaction to the Syrian Arab Army’s attacks against Kurdish areas in Rojava, quickly turned into nationalist, grassroots mass mobilization. In the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Islamists who promoted anti-Rojava rhetoric were faced with mass public opposition and legal consequences.

Hundreds of thousands of Kurds went out into the streets across different parts of Kurdistan in solidarity with Rojava, and the movement revealed the erroneous nature of the claim made by Islamist actors: that, because Kurdish society is majority Muslim, Islamists represent the Kurdish street.

Such a large-scale movement will inevitably reshape Kurdistan’s political landscape and Kurdish social dynamics.

The Limits of Islamist Representation

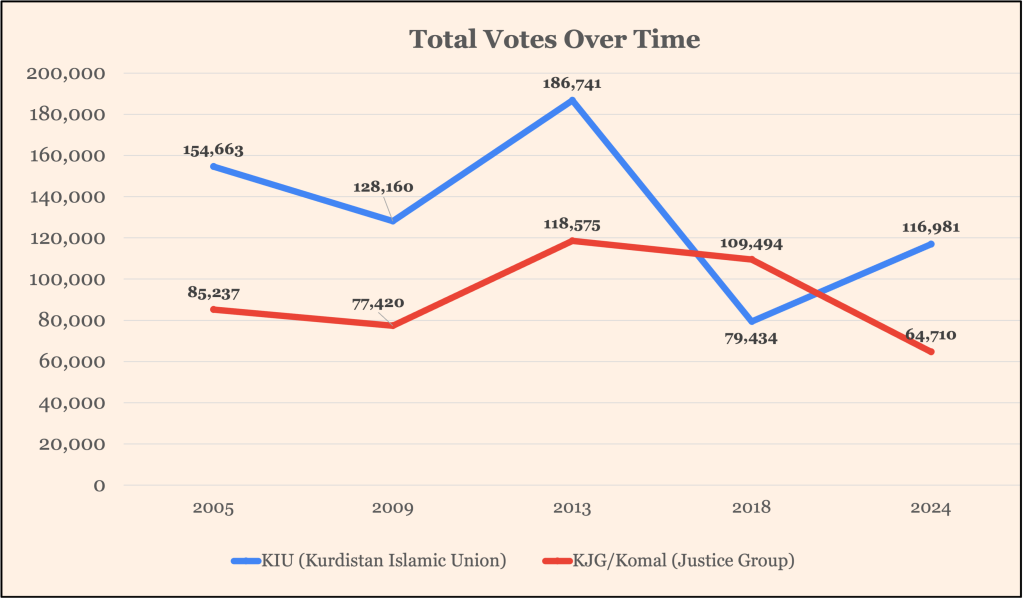

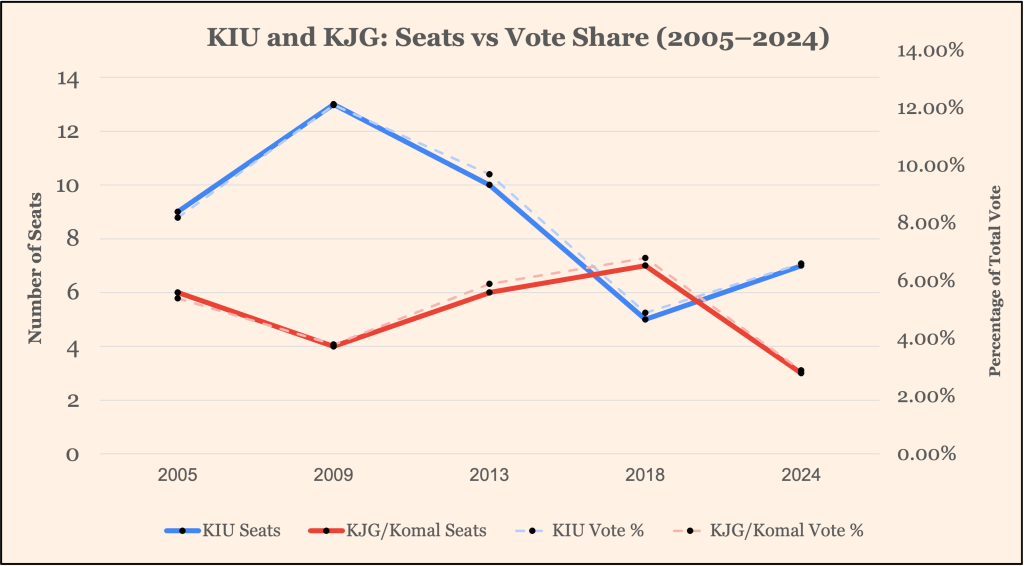

This claim of representation has long been at odds with electoral realities. For years, the two main Islamist parties in Kurdistan, the Kurdistan Islamic Union (KIU) and the Kurdistan Justice Group (KJG), have struggled to secure significant popular support in elections. Even when dissatisfaction with the ruling parties in the Kurdistan Region grew, the KIU and KJG failed to benefit. Instead, their vote shares steadily declined. Taken together, the two parties have lost around 42 percent of their voters since their peak performance in 2013. In the most recent Kurdistan parliamentary elections, their combined vote share was less than 10%.

To compensate for their weak electoral performance, Islamist actors in Kurdistan have, for years, invested heavily in projecting social power. They relied on a form of political exhibitionism designed to signal that, while their support may be limited at the ballot box, they nonetheless represent the moral character of Kurdish society. Through highly visual and carefully organized events, including annual mass hijab ceremonies, Qur’an competitions for children, and mass prayers, they sought to present themselves as commanding a deep religious and social base.

The result was public discourse that detached political legitimacy from electoral performance, which allowed the Islamists to claim an authority that was disproportionate to their electoral standing. They were essentially a puffer fish that held its breath for a while.

This strategy was wide-ranging: across their media outlets, platforms, and mosques, they repeatedly expressed the Islamicness of Kurdish society, while through party structures and affiliated organizations they staged spectacles of mass gathering and mobilization. The result was public discourse that detached political legitimacy from electoral performance, which allowed the Islamists to claim an authority that was disproportionate to their electoral standing. They were essentially a puffer fish that held its breath for a while.

That discourse, however, was unintentionally undermined by the Rojava demonstrations and a series of incidents involving prominent Islamist and Salafist figures.

The first of these incidents were remarks by Mala Mazhar Khorasani, a well-known cleric in Slemani, who publicly attacked the women fighters of the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ). He asserted that women “belong at home” and praised Ahmed al-Sharaa for his “honor” and “proud beard,” even as forces associated with al-Sharaa were killing Kurdish civilians.

Public outrage was immediate, and Kurdistan’s Human Rights Committee filed a lawsuit against Khorasani for disrespecting women. This was followed by statements from Dr. Ali Qaradaghi, a Kurdish Sunni scholar from Slemani and President of the International Union of Muslim Scholars in Qatar, who accused the SDF of violating ceasefires and explicitly endorsed Ahmed al-Sharaa, which triggered further public condemnation and stronger reactions.

The same week, police detained two prominent and outspoken clerics, Mala Halo and Mala Kamaran, in Slemani, after complaints made to the courts accused them of mocking Rojava, ridiculing solidarity protests, and endorsing al-Sharaa.

Yet the most symbolically damaging moment, and the one that most clearly revealed the public’s conditional acceptance of Islamists, occurred in a Mosque in Slemani, where a Friday sermon that failed to express solidarity with Rojava, and reportedly attacked it, was interrupted by worshippers themselves, who forced the cleric to step down from the pulpit. In a viral interview, one attendee remarked, “We are Kurdish first, then Muslim.” A similar incident was reported in Kirkuk.

Indeed, within a two-week span, Islamist and Salafist actors experienced multiple setbacks, while national sentiment over Rojava surged across the Kurdish public. While Islamist groups did participate in the broader humanitarian response, sending aid and assistance as part of the mass relief efforts from the Kurdistan Region to Rojava, this engagement did not translate into political or moral ownership; public sentiment continued being expressed overwhelmingly in nationalist rather than religious terms.

How Did Islamists Lose the Claim and Have They Responded?

The dominant slogans were not appeals such as “Kurds are Muslims too” or “we are one ummah,” but explicitly Kurdish and nationalist slogans like “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî” (Woman, Life, Freedom), “One, one, one, the Kurdish people are one”, and “2+2=1”

The answer lies in the failure of their long-standing investment in political exhibitionism. Prior to the Rojava demonstrations, no single moment had so clearly exposed the fragility of Islamist claims to moral and social representation.

The demonstrations emerged organically and largely ignored the symbolic and discursive repertoire long cultivated by Islamist parties and clerics. While some Islamist actors attempted to frame solidarity through a religious lens, emphasizing that Kurds are “Muslims too”, the language of the street moved in a different direction. The dominant slogans were not appeals such as “Kurds are Muslims too” or “we are one ummah,” but explicitly Kurdish and nationalist slogans like “Jin, Jiyan, Azadî” (Woman, Life, Freedom), “One, one, one, the Kurdish people are one”, and “2+2=1”, a political shorthand for the claim that the four parts of Kurdistan together constitute one greater Kurdistan.

The Islamists’ predicament was further deepened due their own rhetoric – which often resembled that of al-Sharaa’s militias – especially after a directive issued by the Syrian Ministry of Endowments invoked the Qur’anic verse of al-Anfal to legitimize violence against Kurds. This invocation quickly reactivated collective memories of the Anfal Genocide in Iraq, and revelead the genocidal intention of the regime in Syria. The damage was compounded by the widespread perception that Islamist actors and al-Sharaa’s forces emerged from the same ideological tradition, a perception reinforced by visible expressions of sympathy between them.

Today, Islamist responses to this new situation reveal deep anxiety and suspicion toward the mass protests. In a statement issued by the KJG last week, the party claimed that the demonstrations had become a platform for sinful behavior and atheism, and announced its intention to sue media outlets and public figures who, they claim, “turn the struggle against Ahmed al-Sharaa into opposition to God and the sanctity of Islam.” Numerous other Islamist figures similarly accused the demonstrations of promoting opposition to Islam and moral disorder, claims that remain largely unsubstantiated.

The mass mobilizations for Rojava demonstrated that, for a significant portion of the Kurdish public, especially the youth driving the protests, national identity supersedes religious identity – or at least critically engages with religious-political framing. The Kurdish street has articulated itself in a nationalist language, leaving Islamist actors visibly marginalized and struggling to respond.

Notably, this marginalization has persisted despite widespread public dissatisfaction with the ruling class in the Kurdistan Region, a condition that Islamist movements elsewhere in the Middle East have historically been able to exploit – as seen in the cases of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Ennahda in Tunisia, the Justice and Development Party in Morocco, and the AKP in Turkey.

Even as the situation in Rojava begins to settle following the agreement between Kurdish forces and the Syrian state, the movement that emerged in response to the crisis is now shifting from immediate mobilization toward the more difficult task of preservation and now calls for a unified front to safeguard the gains made on the street. How Islamist actors will position themselves within this evolving equation remains uncertain, but what is clear is that the claim that Islamists represent the moral character of Kurdish society has been decisively undermined.

Yad Abdulqader

Amargi Columnist