The Age of Danger Intensifies in a Liberal International Order that is Dying

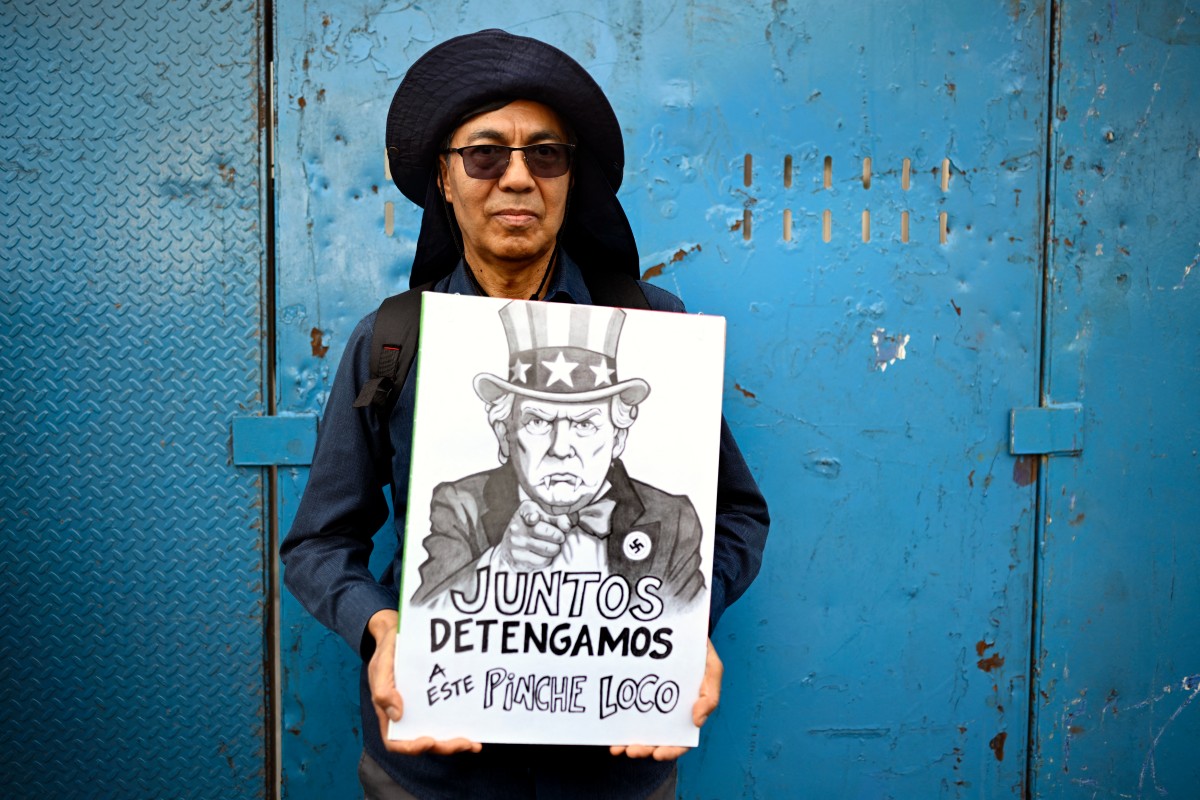

A demonstrator holds a sign depicting US President Donald Trump -as Uncle Sam- and reading: “Together, let’s stop this bloody madman!” during a march in Mexico City on January 10, 2026. (Photo by Alfredo ESTRELLA / AFP)

The recent arrest of Nicolás Maduro, conducted beyond Venezuelan jurisdiction and justified through an elastic interpretation of international law, should not be understood just as an enforcement action against an authoritarian leader. It is a symptom of a deeper and far more dangerous shift in global politics. Sovereignty is becoming conditional, legality is selectively applied, and power once again determines whose leaders are protected and whose are expendable.

Meanwhile, the United States (US) – long the chief architect and guarantor of the post-1945 international system – has begun withdrawing from dozens of United Nations bodies and global institutions under a sweeping executive order. In doing so, they suspend participation in and funding for 31 UN-related entities and 35 other international organisations deemed contrary to American interests – evidently, in a bid to prioritise unilateral sovereignty over collective governance. This retreat from multilateralism – including exits from climate, human rights, and development forums – signals not just strategic recalibration, but an accelerating erosion of the very framework that once constrained great powers and stabilised world order. This is the ‘age of danger’ intensifying – not through dramatic collapse, but through further normalisation.

The illusion of stability hides a deeper decay

At first glance, the international system appears oddly resilient. Wars rage in Ukraine and Gaza, tensions escalate across the Middle East, sanctions proliferate – and yet global markets adapt, trade continues, energy supplies are rerouted, and financial systems carry on. But this is not stability; it is adaptation to dysfunction amid normalised disorder.

Beneath the surface lies the steady erosion of the Liberal International Order (LIO), not primarily because it is under assault from rivals, but because its chief architect, the US, increasingly disregards the principles it once claimed to uphold.

Law for enemies, flexibility for friends

Law is stretched aggressively against adversaries like Maduro, while suspended, reinterpreted, or ignored when it constrains US policy elsewhere

Maduro’s arrest illustrates this shift clearly. Whatever one thinks of his regime, the method matters. Enforcement without consent, legality without universality, justice without jurisdictional restraint – these are not signs of legal strength, but of institutional decay. Only a year ago, Washington was engaging in a very different kind of legal and moral flexibility in Syria. Ahmed al-Sharaa,a former ISIS and al-Qaeda figure, was quietly rebranded and politically accommodated as a pragmatic stabiliser because it suited short-term strategic goals. A man once designated a terrorist was suddenly treated as useful. When the optics became uncomfortable, the support receded, and the episode was quietly buried. International law, once again, proved negotiable.

This is not hypocrisy as an exception; it is hypocrisy as a system. Law is stretched aggressively against adversaries like Maduro, while suspended, reinterpreted, or ignored when it constrains US policy elsewhere. The self-appointed guardian of the rules-based order now treats those rules as optional.

How the Liberal International Order was built and how it’s being abandoned

The LIO was never as liberal or universal as advertised. Built after 1945 under US leadership, it fused American power with institutions such as the UN, International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and, later, the World Trade Organisation (WTO), all of which were actively promoted across the Global South as neutral, rule-based mechanisms. International law was always selectively enforced and sovereignty unevenly respected. But even at its most compromised, the system maintained a shared fiction: that rules mattered, and that power required legal cover. That fiction is now collapsing.

International law has been evidently and increasingly functioning as a tool of convenience rather than a constraint. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine violates the UN Charter, yet enforcement is paralysed. Israel faces plausible genocide claims at the International Court of Justice over Gaza, yet remains diplomatically and militarily shielded by the US. Meanwhile, leaders in weaker states – from Venezuela toSudan – are subjected to extraterritorial enforcement and arrest warrants, while allied figures such as Saudi Arabia’s crown prince,despite credible allegations of state-sponsored murder, remain legally untouchable. This is not accountability but fragmentation.

When multilateralism fails, power walks away

Sanctions now substitute for diplomacy. They are used four times more frequently than in the 1990s, with the US sanctioning roughly a third of the world’s states.

The same pattern runs through global governance. The UN Security Council is paralysed. The WTO’s dispute settlement system has been deliberately crippled by the US itself. The IMF struggles to manage sovereign debt crises worsened by COVID-19. The WHO failed to coordinate an effective pandemic response amid vaccine nationalism. When multilateralism ceased to deliver preferred outcomes, states reverted to unilateralism and coercion.

Sanctions now substitute for diplomacy. They are used four times more frequently than in the 1990s, with the US sanctioning roughly a third of the world’s states. Secondary sanctions extend this coercion extraterritorially, accelerating financial fragmentation and pushing much of the Global South to seek alternatives to dollar-based systems.

The message the rest of the world hears

Maduro’s arrest reinforces a message long internalised outside the West; sovereignty is no longer a universal principle, but a privilege granted through alignment. For rivals like China and Russia, this confirms long-held claims that the ‘ rules-based order’ was always an instrument of American hegemony – now enforced more openly as that hegemony weakens.

For smaller states and vulnerable peoples, the lesson is stark; protection no longer comes from law, but from power. Nowhere is this clearer than from Syria to Iran. In northern Syria, Kurdish communities – who bore the brunt of the fight against ISIS – are once again paying the price of geopolitical expediency. Clashes between forces loyal to Ahmed al-Sharaa and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces have spilled into predominantly Kurdish neighbourhoods, displacing civilians and exposing how fragile and expendable Kurdish political arrangements remain once they cease to serve external interests. In Iran, renewed protest movements driven by economic hardship and demands for dignity have been met with lethal repression and mass arrests,with Kurdish regions once again disproportionately targeted by security forces. What emerges is not simply instability, but a grim pattern: in a dying world order, those who relied most on international norms – stateless peoples, minorities, and protestors – are the first to be abandoned when those norms collide with strategic calculation.

America’s internal crisis is now a global problem

Most dangerous of all is the domestic instability of the US itself. Deep polarisation, institutional decay, and collapsing trust have produced a foreign policy driven increasingly by short-term coercion rather than long-term legitimacy. The peaceful transfer of power can no longer be assumed. Allies hedge, adversaries probe, and law becomes a political weapon.

Gramsci’s warning, revisited

The age of danger has returned not because the LIO is under challenge, but because its guardians no longer believe in it themselves.

Antonio Gramsci described such moments as interregnums – periods when the old order is dying, but the new cannot yet be born. In these moments, he warned, morbid symptoms multiply; violent solutions, charismatic figures, and the abandonment of norms in the name of necessity. Maduro’s arrest, alongside the rehabilitation and abandonment of figures like al-Sharaa, is precisely such a symptom. It signals not the strength of international law, but its instrumentalization.

The post-war order delivered real, if uneven, gains: poverty reduction, declining infant mortality, and reduced interstate war. Its erosion will not produce a fairer system, but a harsher one. A world where sovereignty is conditional, law is selective, and power is unconstrained is not a safer world – even for those who believe they currently sit on top.

The age of danger has returned not because the LIO is under challenge, but because its guardians no longer believe in it themselves. Without urgent reform grounded in legitimacy rather than coercion, today’s morbid symptoms may soon give way to systemic rupture – one from which no state, however powerful, will emerge unscathed.

Bamo Nouri

Bamo Nouri is an award-winning senior lecturer in International Relations at the University of West London, an Honorary Research Fellow at City St George’s, University of London, and a One Young World Ambassador. He is also an independent investigative journalist and writer with interests in American foreign policy and the international and domestic politics of the Middle East. He is the author of Elite Theory and the 2003 Iraq Occupation by the United States.