Kurdish Rights on Trial in the UK

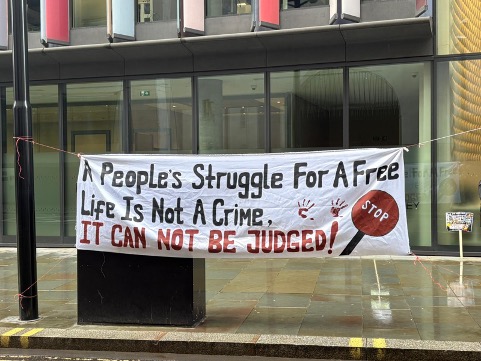

Six members of the United Kingdom’s Kurdish community are facing unprecedented legal proceedings in a major anti-terrorism trial, which is set to have long-term ramifications for not only the UK’s long-criminalised Kurdish community, but also for activism and freedom of speech in the country.

On January 5, London’s Kurdish community convened around the historic Old Bailey court for the first hearings in the trial, which is expected to last three months. They were gathered in support of six community members charged with membership of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a proscribed organisation in the UK.

While the Kurdish community in Britain has long suffered state harassment, never before have they been targeted with such extensive charges. The defendants, who have all pled not guilty, are Ercan Akbal (56), Ali Boyraz (63), Agit Karatas (23), Berfin Kurban (31), Turkan Ozcan (60), and Mucahit Sayak (28).

It is not only Kurds who will be closely watching the outcome of the trial. Political activists and peaceful protestors have come under increasing pressure in recent years due to the UK’s new approach to applying anti-terrorism laws. As Iida Käyhkö, a security studies researcher at London’s Royal Holloway University, has pointed out, anti-terrorism legislation is “increasingly the legal framework and policing strategy brought to bear on a range of political movements” in Britain.

An Assault on the Community

From the outset, the case has been marked by heavy-handed policing, underscoring what Kurdish community representatives in the UK describe as “the collective treatment of a political community through suspicion and securitisation.”

In the early hours of November 27, 2024, as part of an investigation into the PKK, the Metropolitan police’s counter-terrorism unit raided the Kurdish Community Centre (KCC) – a community hub – in Haringey, London. At the same time, the police stormed the houses of six Kurdish community members and arrested them under Section 41(1) of the Terrorism Act (2000), which allows officers to arrest anyone they “reasonably suspect to be a terrorist” without a warrant.

What is the PKK?

The PKK began an armed struggle for Kurdish independence in Turkey in the 1980s, where Kurds have long faced state brutality, displacement, mass incarceration, assassinations, and forced assimilation policies. Ankara has used its conflict with the PKK to enact draconian emergency laws in Kurdish-majority regions, further restricting Kurdish life.

The PKK’s fight spearheaded a broader popular movement pursuing democracy, civil society gains, and women’s rights through social activism, parliamentary politics, and grassroots organising inspired by the political ideology of PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan – the Kurdish Freedom Movement (KFM). The PKK itself, however, disbanded and laid down its weapons in May 2025, committing itself to a peace process with the Turkish state.

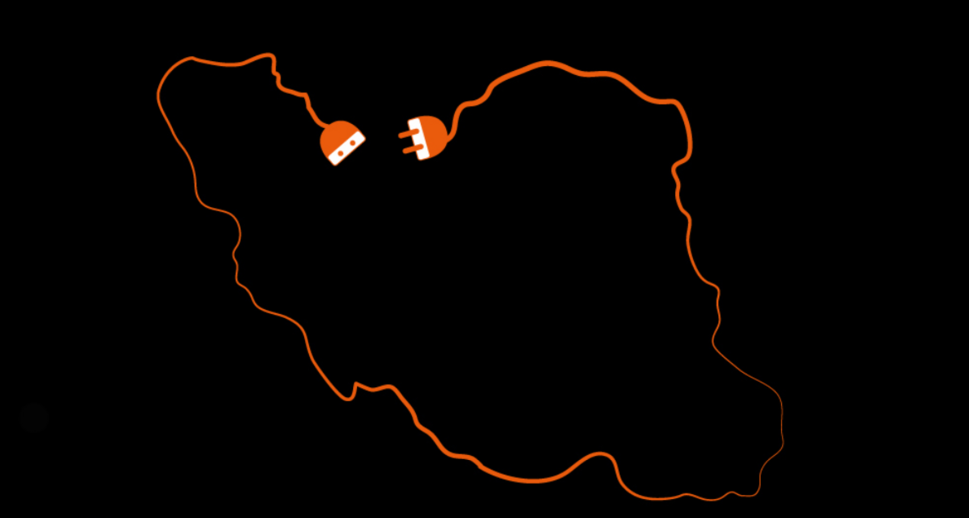

Why is the UK criminalising Kurds?

The PKK remains a banned organization by most international bodies and Western countries. In the UK, the PKK has been formally designated a terrorist organisation since 2001. However, no international court has found the PKK to meet this definition.

In 2020, Belgium’s highest court ruled that the PKK is not a terrorist organisation, but a legitimate party to a non-international armed conflict. Yet intensive lobbying by Turkey has maintained the criminalisation of Kurdish activities across the diaspora.

Turkish pressure has sought to narrow avenues for Kurds to assert their identity and politics, with the Turkish Foreign Ministry furiously summoning numerous European ambassadors following pro-Kurdish demonstrations or events in their respective countries.

Many Kurds in Europe risk heavy consequences should they express their political views: from police brutalisation at marches, to being arrested for carrying certain flags or singing songs. This includes the UK, where two activists were recently handed terrorism sentences for displaying the PKK flag at a demonstration. Police can deem any activities under the remit of the KFM – artistic productions, cultural celebrations, educational programs – as “supporting a terrorist group”.

Law As an Instrument of UK Security Policy

The decision to seek punitive sentences against peaceful Kurdish activists in the UK runs parallel to the British government’s broader policies in recent years, as Britain has centred “counter-terrorism” in state security and policing. This has developed in tandem with an expansion of criminal offences that restrict protest and curtail collective action, leading to criminalisation based on “characteristics, social networks, identity, beliefs, etc.,” according to Frederica Rossi, a criminology researcher at London South Bank University.

Responsibility for “counter-terrorism” has also bled in the social sphere, as seen with the UK’s Prevent program. Supposedly aimed at safeguarding individuals at risk of radicalisation, it employs a vague definition of extremism, with even non-violent dissent taken as a potential indicator. This “casts a ‘national security’ net across a vast array of civic spaces”, says Rights and Security International.

The “chilling effect” of this, as Amnesty International found, is the stifling of public discourse: “People have modified their behaviour, including refraining from participating in protests and from expressing their political and religious views”.

The Online Safety Act (2023), meanwhile, obliges technology companies to remove “terrorist content”. This means commentary on a proscribed group or expressions of belief in line with its platform are heavily restricted. All these tactics have also been applied to the UK’s Kurdish community, often with less visibility than other targeted groups.

While appearing to work through individualised mechanisms of prosecution, sweeping “anti-terror” legislation provides cover for the targeting of whole groups. The effects of PKK proscription loom large over the lives of Kurds, beyond those politically involved in Kurdish liberation.

With Turkey continuing its efforts to globalize the criminalization of Kurdish political expression, and the UK increasingly willing to use its counter-terror legislation for political purposes, perhaps the trial of the six Kurdish individuals is no shock. Yet this trial still marks a serious escalation in the repression of the Kurdish community in Britain.

The coming months of court proceedings will thus not only determine the fate of the Kurdish defendants but also set a precedent for how easily the UK authorities can wage “lawfare” and wield the judicial system to pursue political agendas.

Eve Morris-Gray

Eve Morris-Gray is a freelance writer focussed on civil society movements and democracy.