Iraq’s Quota System Silences Minorities

In Iraq’s 2025 parliamentary election, the country’s large parties have dominated the quota seats reserved for religious and ethnic minorities in the Council of Representatives. Christian activists and groups argue that this shows how powerful blocs influence who speaks for them, often without their consent.

The Quota System

Iraq, though dominated by a Shia Arab majority, is home to many different ethnic and religious communities. To ensure that minority groups are not left without a voice in the country’s politics, the Iraqi constitution has guaranteed a number of quota seats for these groups.

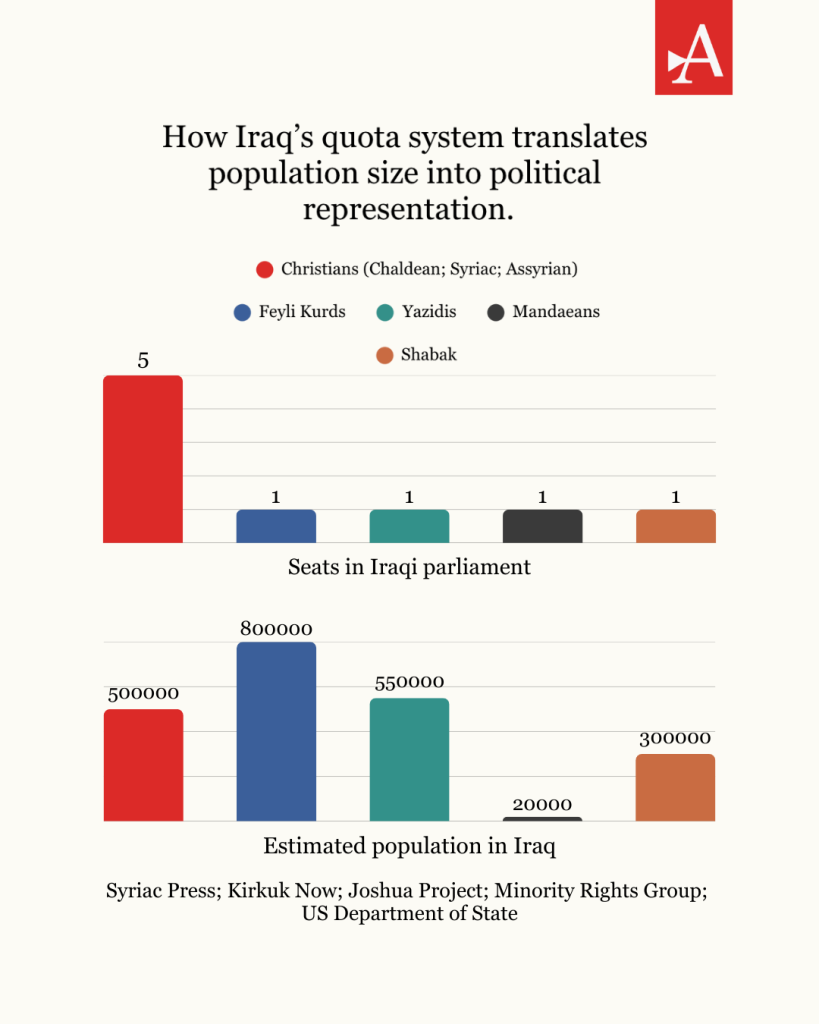

Out of 329 seats in Iraq’s parliament, nine are reserved for minorities. Five are Christian seats, allocated to Baghdad, Nineveh, Erbil, Duhok, and Kirkuk. The remaining four seats are for Yazidi, Shabak, Sabean Mandaean, and Feyli Kurd representatives in Iraq’s provinces.

The quota seats do not have a separate voter registry, meaning that any Iraqi citizen can vote for a quota candidate, regardless of religion or ethnicity. This fact sits at the center of the current controversy.

Parties such as the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Babylon Movement have usually encouraged their supporters to back particular quota candidates, to prop up the candidate and provide them with far more votes than they could attract from just their own communities. While this can boost minority voices, oftentimes it leads to political influence and even outright dominance over the seats.

In the 2025 Iraqi national elections, the KDP secured five minority quota seats that it backed. As a result, the party now holds three of the five Christian seats in Iraq, which, historically, had been dominated by the Christian, Babylon Movement led by Rayan al-Kildani. In turn, Babylon managed to retain only two Christian seats in this election, down from four in 2021.

“It has become an avenue for powerful parties to control minority representation and boost their own seat totals in a cost-efficient way.”

Of the remaining quota seats, Shabak representation in Nineveh remained with long-time incumbent Waad Qado, who is seen as genuinely popular among many Shabaks. And the Sabean-Mandaean seat in Baghdad went to a candidate backed by the Faw–Zakho list, a Shia-leaning liberal alliance that also won a general seat.

Max J. Joseph, an Assyrian activist and PhD candidate at Chicago’s Loyola University, shared his views on the quota system: “The quota has been hollowed out by powerful non-Christian Assyrian actors.” He said that often, people outside the community, supported by larger parties, become the deciding factor in Iraqi Christian politics: “It has become an avenue for powerful parties to control minority representation and boost their own seat totals in a cost-efficient way.”

Christian Representation

The Iraqi Christian population has very little influence over the country’s politics, and according to church leaders there are fewer than 500,000 Christians left in the country – a number that’s shrunk since ISIS swarmed the area in 2014. The relatively small number has made it easier for the quota seats to be influenced by non-Christian sides.

Christian parties, however, say the problem is not just the numbers, but who those elected officials ultimately answer to.

The Beth Nahrain National Union Party, a long-standing Assyrian Christian group, refused to take part in the 2025 election. In a statement, it said quota seats for the Chaldean, Syriac and Assyrian community had been “marred by distorted practices” and no longer offered real protection or representation.

The party’s main objection is that any Iraqi can vote for Christian quota seats. It describes this as “manipulation” and a “theft of the will” of the original community. They have accused Kurdish and Shia actors of exploiting the system by mobilizing non-Christian voters and supporting candidates who are loyal to larger blocs, not to minority interests.

Beth Nahrain has claimed that, except for a small minority, most Christians in the Nineveh Plain and other areas stayed away from the ballot box. As they argue, the boycott is due to a loss of faith in the electoral process and a widespread belief that quota outcomes are “pre-decided”.

Yazidi Representation

Similar concerns are emerging among Yazidis, many of whom live in the northern province of Nineveh and in IDP camps in the Kurdistan Region – due to ISIS’s genocide against the Yazidis and the attacks on Şingal (Sinjar).

Unlike the quota candidate, Yazidi Cause contested general seats.

Iraq reserves one parliamentary seat for a Yazidi representative. In the 2025 election, the KDP retained that seat, but the seat’s political relevance has been overshadowed by the performance of a new electoral list: Yazidi Cause.

Unlike the quota candidate, Yazidi Cause contested general seats. Its campaign focused on Yazidi areas, IDP camps, and communities that experienced Islamic State atrocities and the slow reconstruction of their destroyed homes.

The list has secured more than 6,000 of the roughly 13,000 votes cast in Yazidi displacement camps in Duhok, an unprecedented result for a party outside the KDP. It also gained significant support in Şingal and Sheikhan, two areas with high Yazidi populations. Its leading figure, Murad Ismael – a board member of the Sinjar Academy – won close to 23,000 votes and entered parliament on a general seat rather than through the quota seat.

Kurdistan’s Parallel Battle

Until early 2024, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) parliament reserved 11 seats for religious and ethnic minorities. In February 2024, Iraq’s Federal Supreme Court abolished the 11 minority seats and cut the size of the Kurdistan Parliament from 111 to 100 members at the request of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) – the second largest party in Iraqi Kurdish politics, after the KDP. Months later, the Iraqi Supreme Judicial Council’s election committee restored five minority seats for the Kurdistan Region. These were distributed among Erbil, Sulaymaniyah, and Duhok.

Under the new set-up, the KDP is reported to control three of the five minority seats, while the remaining two are seen as being close to the PUK. In the past, community representatives have said that this leaves little room for independent organizing or for genuine minority voices in the KRG parliament.

Calls for Reform

In its post-election statement, Beth Nahrain National Union proposed a separate electoral register for Christian voters. Under this plan, only Christians would be able to vote for the five Christian quota seats in the Iraqi parliament, and the same for other minority groups.

Supporters say such a change would prevent larger parties from mobilizing voters from outside minority groups to decide who fills those seats, and would force elected officials to rely on, and answer to, their own communities. They argue it would restore confidence in a mechanism many now view with suspicion.

“All independent Christian Assyrian parties in Iraq have called for [reform] for over a decade,” Joseph said. “All major churches have called for it. There have been protests across Iraq calling for it, but both Baghdad and Erbil ignore this demand, saying it is logistically unworkable.”

“If Iraq wishes to keep its quotas,” Joseph continued, “then make them fulfill their intended purpose by listening to the demands of the people instead of satisfying major parties.”

Renwar Najm

Renwar Najm is an Iraqi Kurdish journalist with a career that began in the early 2010s at the esteemed Awene newspaper. He holds a master’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of Kent and Philipps University of Marburg.