How the Suweida Crisis Deepens Divisions in Syria

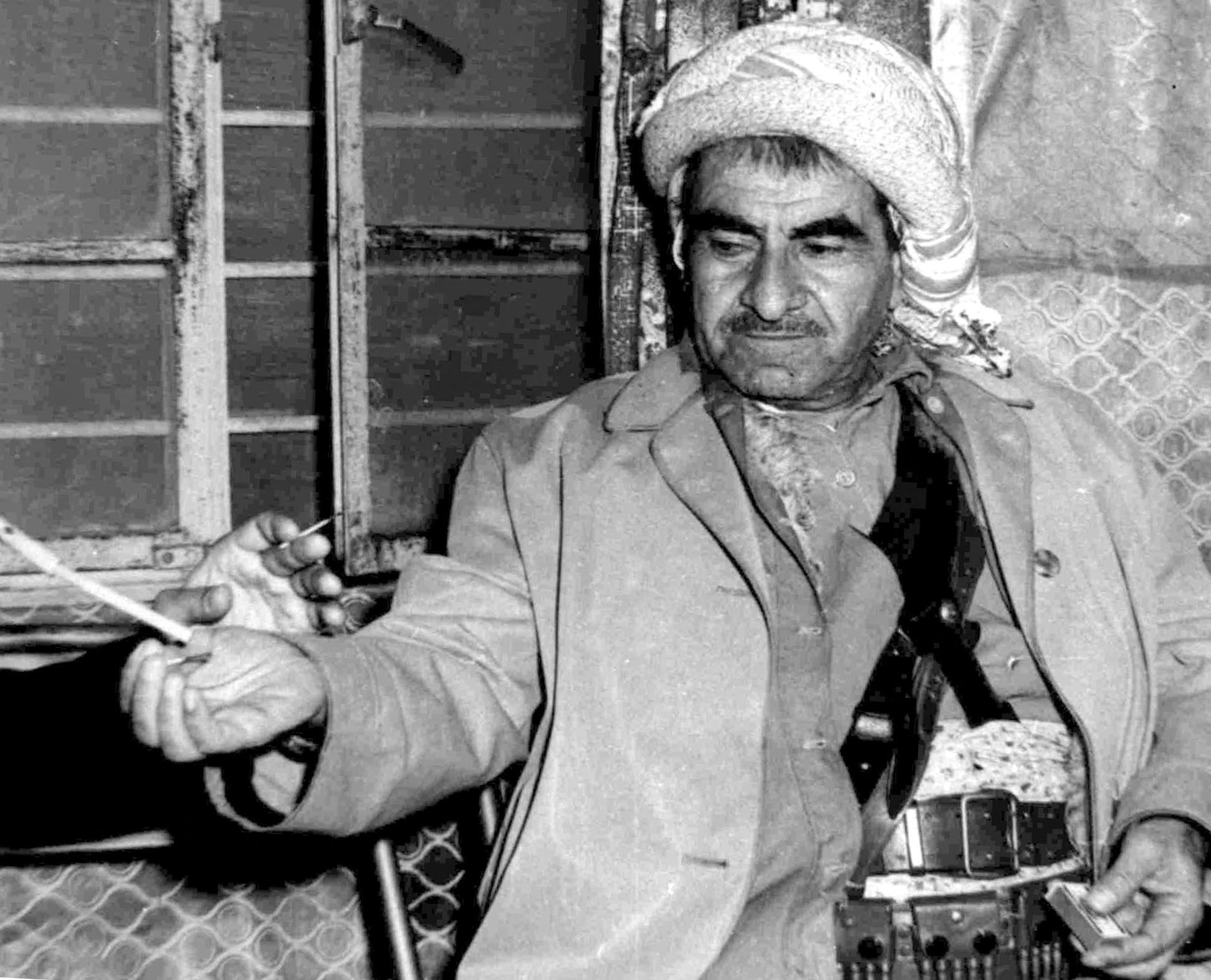

Credits: Santiago Montag

Picture Credit: Santiago Montag

Syria’s southern Suweida province descends into sectarian violence, leaving thousands displaced, services collapsed, and civilians enduring severe humanitarian suffering.

Recent months have plunged the southern Syrian province of Suweida into an unprecedented spiral of violence. The crisis launched in July with the kidnapping of a Druze man and quickly escalated into clashes between armed Bedouin tribes and local Druze militias. Under the pretext of restoring order, the interim government security forces intervened militarily, which led to a large-scale humanitarian disaster.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, at least 1,677 people have died; this includes 452 executions, 250 of which were women and children.

Throughout the conflict—which included mutual reprisals, massacres, Israeli airstrikes, and the mass mobilization of fighters—dozens of videos circulated on social media showing executions, torture, and extreme acts of violence against the Druze community. Organizations such as Amnesty International have condemned the brutality. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, at least 1,677 people have died; this includes 452 executions, 250 of which were women and children. Despite the fragile truce at the province’s borders, locals report daily attacks, indicating that the situation remains volatile.

The Collapse of Suweida

The province of Suweida is now largely isolated, under strict control by the interim government’s security forces. In this de facto blockade, Suweida has experienced almost total collapse of essential services, leaving the overall situation in a “severe” state, according to Adam Abdelmoula, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Syria.

“The electricity cuts out for days and then comes back on,” explains Sham, whose real name has been changed for safety reasons, to The Amargi. “The pipes connecting us to Damascus have been attacked by General Security forces for two months,” she continues. “Now we are getting water from Daraa, but these attacks keep cutting the flow.”

Writing via WhatsApp from the heart of the southern city, the young woman adds, “The majority of food stores are empty except for the vegetable market from the western region, but prices have risen dramatically.”.

“We are sheltering thousands of people in our homes, but our capacities are stretched beyond their limits.”

Stressing the psychological and material suffering of the inhabitants of Suweida, Sham says: “More than 30 villages have been burned to the ground, so much has been lost,” she continues. “We are sheltering thousands of people in our homes, but our capacities are stretched beyond their limits.” In her words, the atmosphere is shaped by “a mixture of sadness and anger.”.

Kinda, a humanitarian worker based in Suweida, tells The Amargi, “Aid convoys and commercial goods are arriving in the province, although insufficient to meet the needs of the residents.” This is linked to another issue: “People have no money due to the lack of salaries or other sources of income due to the current situation.”

Picture Credit: Santiago Montag

A Dire Healthcare Situation

Meanwhile, hospitals are operating at minimal capacity. Kinda describes a shortage of medicines,fuel, and other essential facilities. “Because of the critical shortage of medical supplies, including cancer medications and insulin, some patients have died,” she details.

“Winter is coming in two months, and our province is extremely cold; there will be no heating sources without fuel or wood,” Kinda notes with concern during a phone call. Another problem on the horizon is the delay in “the opening of schools, which have become shelters for displaced people,” she concludes.

Changing Power Dynamics in Suweida

As the humanitarian crisis deepens, power dynamics within Suweida are shifting. According to a report by the UN-related International Organization for Migration (IOM), in August, about thirty local armed factions from Suweida came together under the name of ‘National Guard Forces’, taking responsibility for security and stability across the governorate.

This group pledged allegiance to the spiritual leader Hikmat al-Hijri, known for his past links to the Assad regime and for seeking international help, including from Israel. Although he initially had little influence among the Druze community, this changed as events developed in July. The violence led many Druze to seek refuge with those who could guarantee their survival in the context of a sectarian regime.

A Crisis in Daraa

The UN estimates that more than 192,000 people have been displaced by the fighting.

The conflict has caused a massive displacement of the population. The UN estimates that more than 192,000 people have been displaced by the fighting. Due to the sectarian nature of the conflict, the displaced have been divided between Suweida, Daraa, and the rural areas of Damascus. Many are leaving the country in small waves.

Following the ceasefire reached on July 19 through the mediation of the United States and Arab countries, thousands of Bedouin families have been relocated to dozens of schools functioning as makeshift shelters.

Amina, a 30-year-old Bedouin woman, lives displaced with her family in al-Hrak, a small village east of Daraa. “We have been here since the crisis started, but things are getting worse as we wait to return, God willing,” she says, her voice filled with worry. “We get some food, but we have no way to cook it—there is no gas,” she claims as she tries to light a small fire in the courtyard of the school where she lives with 50 other families. “For now, we have a roof over our heads, but in two weeks, school will begin, and they will likely kick us out,” she adds, distressed. She is a teacher who fled from al-Masra, a village in Suweida, where all her children were born.

Around her, a group of women who also live in the school claim that they fled due to fears of attacks from the Druze factions, particularly from al-Hijari. Their hope is that some form of reconciliation will be reached. For Durra, an elderly Bedouin woman, “this doesn’t make sense; we have lived peacefully for decades, we never had any problems.” She asserts that these confrontations are “something new.”

Picture Credit: Santiago Montag

In Mleiha al-Gharbiyeh, another village in rural Daraa, Bashar al-Hraki, the local mukhtar (chief of village), is using the municipal building to store shipments delivered by the World Food Bank for distribution among the people. “Before the crisis, the situation was bad, but now it’s much worse. We have over 8,000 people in this small village who came from Suweida, both Bedouins and Druze. Everyone is welcome, everyone is Syrian,” the 60-year-old mukhtar asserts.

“Families are living in schools, private homes, and tents around the area,” al-Hraki describes. “Israel is behind all this, stealing our land. Its intervention has complicated everything, and this is a very delicate moment for our country where sectarian problems resurfaced after the fall of the regime,” he says in his office, as a group of men arranges boxes of supplies.

Sitting in a tent, Abdullah al-Wadi angrily comments that “since December 8, we have noticed a change in attitude towards us,” blaming Al-Hajari’s faction. “My family lived in Suweida for over 100 years, and we never had a dispute with the Druze,” he says in disbelief, as he watches a video with explicit content showing the desecration of the body of a supposed Bedouin fighter.

In another school-turned-shelter, Izra, along with her sister, mother, and all her children, live in a classroom surrounded by blankets and piled clothes. According to Izra, the whole family was held hostage for two weeks in Qanawat village in Suweida by groups associated with al-Hijri. She claims that they were captured while fleeing toward Daraa. “We were with other women and children, about 15 people,” she describes. “A woman gave birth there, and she is still kidnapped, as far as we know.”.

A Wounded Syria

The government’s handling of the crisis has isolated Suweida, casting the conflict in a sectarian light at a critical moment for the country’s reconstruction after 14 years of war.

The crisis in Suweida has not only caused a humanitarian disaster but also deepened sectarian rifts within Syria. As fragile calm lingers, the underlying causes of the conflict remain unresolved. The government’s handling of the crisis has isolated Suweida, casting the conflict in a sectarian light at a critical moment for the country’s reconstruction after 14 years of war.

Each faction has created its own narrative to mobilize its base under external influence, leaving civilians caught in the crossfire. The suffering of families like Sham’s, Amina’s, and Durra’s is a stark reminder that these divisions are no longer just political—the crisis is linked to the prolongation of a conflict that left lives shattered, communities scattered, and a country on the brink of collapse.

Santiago Montag

International journalist and photographer based in Damascus