How did the Syrian Struggle for Democracy End with Massacres of ‘Alawis?

Cover photo by: Hossam el-Hamalawy (under Creative Commons License Attribute 2.0)

In an age dominated by the rapid pace of digitalization, massacres seem to impact people like trending social media posts—invoking sudden emotional reactions before fading away. The recent massacres on the ‘Alawis in the coastal regions of Syria is one example.

Between the 7th and 9th of March 2025, massacres against the ‘Alawis were committed by the Syrian interim government headed by Ahmed Sharaa. Unimaginable and horrific violations against ‘Alawis went viral on social media. Justice for the victims and accountability for the perpetrators remain elusive.

A few months after the ‘Alawi massacres, images of atrocities similar to those witnessed earlier on the Syrian coast were repeated—this time against a different minority: the Druze in Suweida province. Armed groups linked to the Defence Ministry of the Syrian interim government carried out killings, executions, abductions, lootings, village burnings, forced displacement, and sexual violence. Hundreds of corpses of innocent Druze were found in the streets or inside homes. The moustaches of Druze religious leaders were forcibly shaved—an act widely interpreted as a symbolic assault on Druze dignity.

The regime of Bashar al-Assad fell in December 2024. For over a decade, the rule of the Ba’ath Party in Syria was depicted by many international and regional powers, along with the opposition they backed, as a force of evil that had to be eliminated. But now that the regime is gone, why does extreme violence continue in Syria?

To understand this present, one must look at history. The historical roots of these massacres lie with the nature and trajectory of the so-called Syrian revolution.

To get straight to the point: the massacres of ‘Alawi and Druze communities today— and others that may follow—stem from the opposition movement’s failures to meet initial democratic demands of Syrian protesters. Counter-revolutionary forces, backed by external actors, fought any existing democratic principles by Islamizing and sectarianizing the movement, while the Assad regime used brutal repression and sectarianism to derail its goals.

From Freedom to Sectarianism

Inspired by the courage of people across North Africa and the Middle East who rose against the repression and authoritarianism of their nation-states during the so-called Arab Spring, Syrians took to the streets against the Assad regime in March 2011. They demanded freedom and dignity against decades of dictatorship. Like others in Arab countries, the protests in Syria were often driven by a longing for freedom, democracy, and economic justice.

In the face of just and universal demands, the Assad regime labeled the entire movement as ‘sectarian sedition’—a conspiracy by regional and international powers. This approach incited fear and broke social solidarity among people.

By portraying the protests as mainly driven by a foreign-backed Islamist extremist conspiracy, the Assad regime deepened the seeds of distrust and panic—particularly among minority communities—to legitimize itself as the ‘defender of minorities’.

This manufactured fear-based strategy had two goals. First, it consolidated the regime’s loyalist base and depicted the regime as the source of stability within Syria. Second, on the level of international legitimacy, it played on the Western discourse around the “war on terror” to gain support and justification to suppress the uprising.

Another move was the timely release of Islamist extremists from prison during the first months of the popular protests, some of whom later became top leaders in groups like Syria’s al-Qaeda branch Jabhat al-Nusra, which rebranded itself as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). The Assad regime knew that these groups would actively contribute to the Islamization and militarization of the popular movement. This helped delegitimize the opposition in the eyes of both domestic and international audiences and justify brutal crackdowns.

The Assad regime polarized society and secured its survival by relying heavily on propaganda, state-controlled media, and local actor supporters, thereby enforcing sectarian divisions. Although sectarian sentiments existed before 2011, they were neither hegemonic nor highly politicized. Other identities or ideologies, such as nationalism, class, and ethnicity, had much more substantial weight than sectarianism. Gradually, sectarianism was reified through violent acts (massacres, abductions, etc.) and the deepening of divisions via militias and other institutions along sectarian lines.

Although the Assad family comes from an ‘Alawi background, this did not translate into protection for the ‘Alawi community. The regime’s rule was authoritarian and patrimonial; under it, many ‘Alawis faced repression, were arrested or killed, and lived in poverty.

Islamization of the Revolution

In June 2011, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) was formed. A new era began—one that could be called the militarization of the movement, sustained by foreign-backed Sunni Islamism. Months into the crisis in Syria, foreign powers began to intervene openly. The Gulf states (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates), Turkey, and Western countries like the U.S. recognized and supported Syrian opposition structures in exile—first the Syrian National Council (SNC), and later the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (NC)—as the official political representatives of the Syrian people. This recognition included initiatives to form a government-in-exile.

The Muslim Brotherhood dominated these bodies as it had the broadest oppositional base with Syria, including the allied Free Syrian Army. It received significant support as a result. The war escalated even further when Shi’a political Islam representatives—Iran and Hezbollah—militarily intervened on behalf of the Assad regime. On the other side, the western-aligned bloc backed the Muslim Brotherhood-led FSA. Syria became a battlefield in a sectarian war fuelled and supported by regional and international forces.

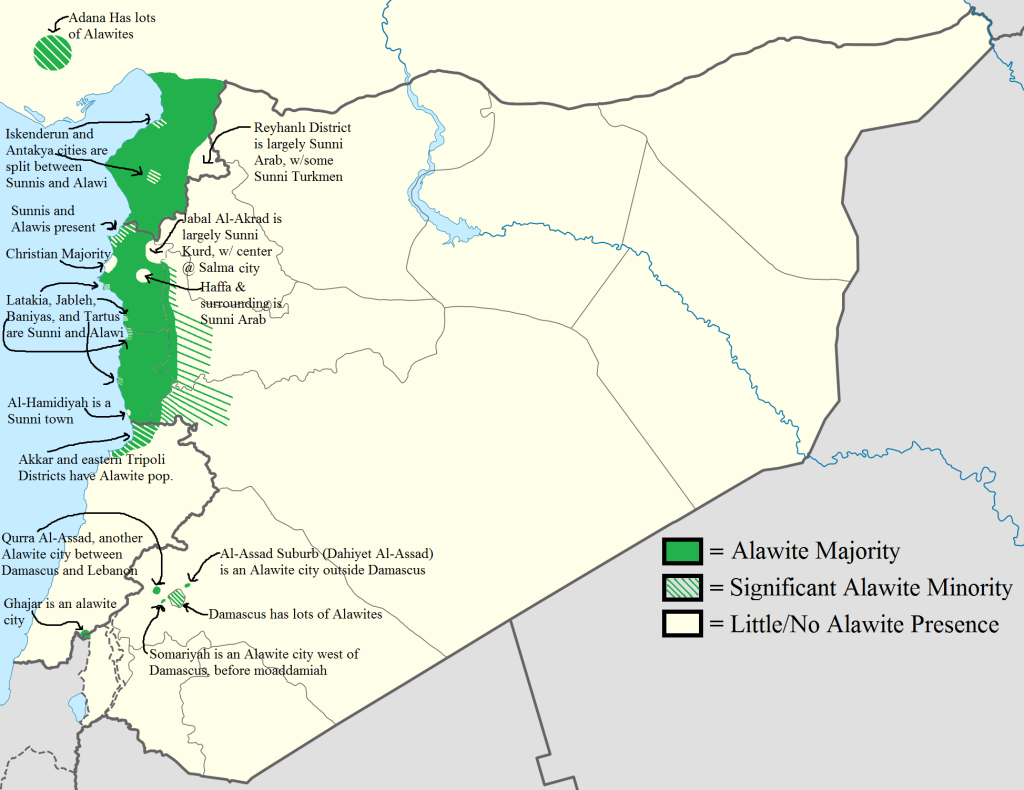

Geographical distribution of the Alawite community in Syria. Source: Wikimedia

The FSA lacked central leadership and a unified ideology. Many of its constituent groups began adopting sectarian rhetoric, attracting more Syrian and foreign fighters and securing political and financial support, especially from Turkey and the Gulf. Moreover, sectarianism reached its climax in June 2013. A body of Muslim scholars convened in Cairo to issue a call for jihad against the Assad regime. Over 70 Islamic organizations were involved, including the International Union of Muslim Scholars led by Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the Muslim World League, the Saudi Council of Senior Scholars, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the League of Scholars of the Levant. They claimed that what was occurring in Syria was a “war against the Islamic nation”. In this highly sectarian and charged religious environment, Islamist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra thrived and developed a permanent presence in Syria.

Armed Islamist groups framed ‘Alawis as non-believers who support what they defined as the ‘Alawi Assad regime. In their rhetoric, killing ‘Alawis was essential to the struggle against the regime.

By framing the Syrian revolution in certain ways, Gulf media—particularly Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya—mobilized opposition groups and manufactured public opinion along sectarian lines rom the first months of the revolution. Their coverage strengthened the influence of Salafist-Islamist actors and helped entrench them within the opposition, while democratic and progressive voices were pushed aside.

Political Money

Foreign powers funded different groups according to their own interests and objectives in the region. This sometimes occurred in a coordinated manner, as in the covert Operation “Timber Sycamore”, which was led by the CIA and also involved Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, Israel, and several Western countries to support the rebels. A strategic military front failed to emerge amid the chaos that these opposing initiatives brought about. In this context, Islamist extremist groups like Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), originating in al-Qaeda, managed to overpower other factions and groups.

State actors contributed to the sectarianisation and militarisation of the movement by marginalising democratic forces who were rejecting sectarianism. The policies of both the Assad regime and its allies, as well as the regionally and internationally backed opposition, wiped out many of the original ideals and goals expressed by Syrian revolutionaries in 2011.

The sudden fall of the Assad regime is primarily attributed to geopolitical factors and decades of war and economic crisis. Indeed, Assad’s allies (Russia, Hezbollah, Iran) have declined in power over the past few years, especially after October 7. As a result, there was no significant fighting before and during Assad’s fall; HTS advanced toward Aleppo and, within a very short time, took control of Damascus and formed a dictatorial interim government.

In sum, HTS and other Islamist groups that make up the core of the interim government—ideologically driven by sectarianism and Arab nationalism—had already been framing non-Islamic and non-Arab communities as enemies before committing massacres against ‘Alawis. The consequences of this are also seen in the attacks on the Druze.

Such massacres are deeply connected to the failure of the Syrian opposition movement, which was undermined by forces that now comprise the core of the interim government in Damascus, backed diplomatically by regional and western powers. As long as the interim government remains in power, it is likely that more massacres will happen against different ethnic and religious minorities.

By Shiraz Hami and Cihad Hammy

Shiraz Hami is from Kobanî/Rojava and studies political science at the University of Hamburg.

Cihad Hammy

Cihad Hammy studies English and American Studies (Master’s) at the University of Hamburg. He is a researcher and the co-editor of Rojava in Focus: Critical Dialogues.