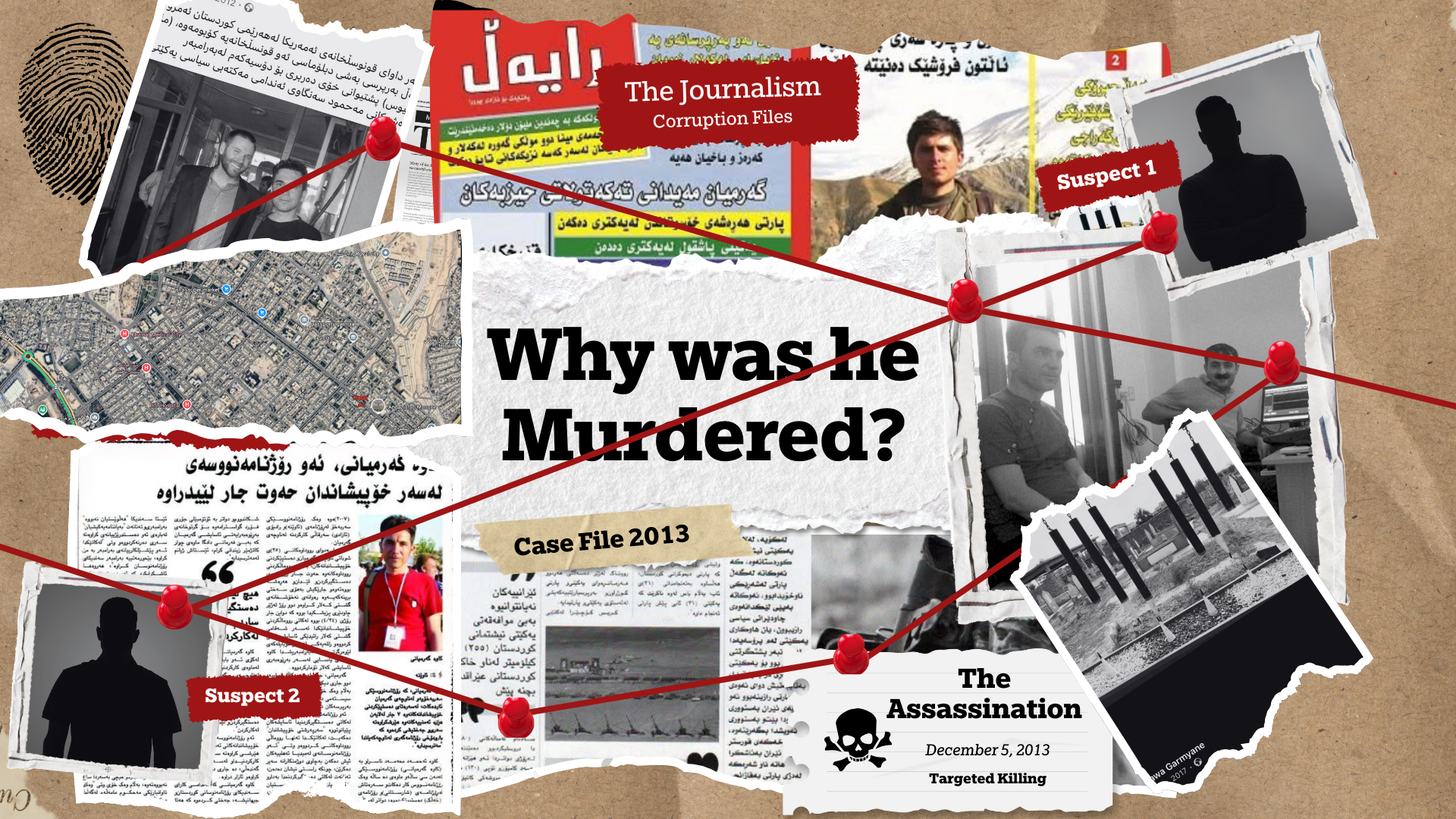

12 Years On: Who was the Journalist Kawa Garmyani and why was he Murdered in Kurdistan?

“Amed began asking about his father when he was five years old, and his questions continued to change as he grew up. After he understood his father is dead, he would often lock himself in his room and cry his heart out. He keeps saying he’s different from his friends and classmates, that he’ll always be deprived of his father’s presence in this life.” Shirin Amin, Kawa’s widow and the mother of their only child, told The Amargi.

Shirin added, “At the age of eleven, Amed learned about the anniversary of his father’s assassination. He insisted on attending the commemoration at his father’s grave, where his tears revealed to all of us the depth of the tragedy and injustice he suffered; an innocent boy deprived of his father before he was even born.”

Kawa Ahmed Mohammed, known as “Kawa Garmyani”, was born into a poor family near the shores of the Caspian Sea in Rasht, Iran, in 1979. He left the lush Iranian north to return to the warm plains of his hometown, Kalar in South Kurdistan (Iraqi Kurdistan), in 1984. And here, he began his education.

Like many of his generation, the events of the two final decades of the 20th century were formative in Kawa’s life: the brutality of the Anfal Genocide – which claimed the lives of nearly 200,000 Kurds and razed more than 4000 Kurdish towns and villages in South Kurdistan in the late 1980s – and the bloody Kurdish Civil War of the 1990s which fractured Kurdish society. He dropped out of school in the 8th grade and put his energy into earning what he could to help his family survive; a responsibility that fell on him, especially after his father’s death – a Peshmarga freedom fighter who was killed by Kurdish jashes (Kurds who collaborated with Sadam Hussein’s regime). From that moment on, Kawa had to work to support his family.

He married Shirin Amin on December 12, 2012. Shirin’s family was also victims of Iraq’s Ba’athist regime: her father was buried alive during the Anfal Genocide.

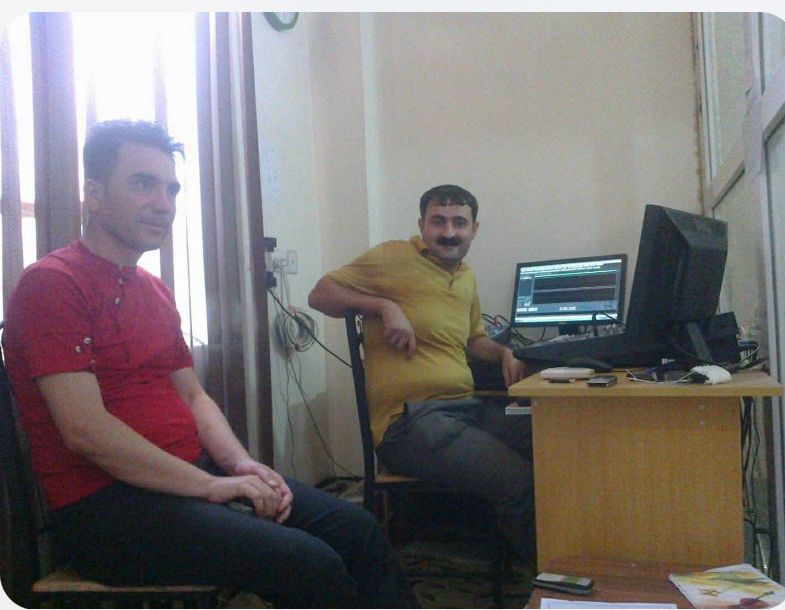

Speaking to The Amargi, journalist Azad Osman, a close friend and longtime colleague of Kawa Garmyani, described him as a young man whose defining trait was a spirit of solidarity that never wavered. “Kawa had this beautiful quality. He was always ready to help, always standing with others.”

Kawa’s Work

Kawa Garmyani began his career in 2002 as a photojournalist, and not long after, he was publishing critical articles and reports in various newspapers and magazines to shed light on the realities of his hometown.

In 2007, he began as a reporter for the Awêne newspaper, while also serving as a correspondent for the outlet Regay Kurdistan.

Throughout his eleven years of journalistic work, he was repeatedly subjected to arrests and beatings by security forces, and threats from party officials because of his reporting.

He suffered the most severe attacks in 2011 in Kalar, where he was covering protests against corruption and nepotism in the Kurdistan Regional Government. In that period, he was attacked, arrested, and brutally beaten seven times. In one of those incidents, he was attacked so brutally that he had to remain under doctors’ supervision for two nights in the hospital due to his critical condition.

Later, in an interview with Awêne, he described how security forces had struck him with sticks and punches to the face. He said they even forced their hands into his mouth to choke him, as they accused him of participating in the protests.

But Kawa Garmyani was unwavering even in the most difficult moments. Azad Osman relayed the story of how, in late 2011, despite his own troubles, when Dang Radio – an independent radio station set up by independent journalists –was attacked and its offices were looted, Kawa was among the first to stand in solidarity with its staff.

“He opposed the attack fiercely,” Osman said. “He stayed with us and supported us; financially, morally, and especially by taking the case to the public and giving statements to the media whenever needed.”

In 2012, Kawa Garmyani launched his own magazine, “Geran” – Kurdish for “Search”. On July 25, he published a critical article about the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) party official Mahmoud Sangawi. A few days later, a telephone conversation uploaded to YouTube purportedly recorded Sangawi threatening Garmyani, calling him names, and making death threats. Garmyani filed a lawsuit against him in court, and Sangawi did not deny the authenticity of the phone call. After the journalist’s death, Sangawi was detained in January 2014 but was then released due to a lack of evidence supporting the case of his being the murderer.

On September 10, 2012, Kawa Garmyani, as editor-in-chief, published issue number 14 of Rayal magazine, where he mainly reported on corruption and human rights abuses in the Garmyan area. It was the last magazine issue he worked on, published shortly before his assassination.

Later that year, Kawa Garmyani confronted another PUK political official, Adnan Hama Mina, after publishing a report regarding his involvement in seizing public land.

Kawa’s Death

According to the Kurdistan Tribune, Kawa met with the US consulate official Matt Mason in Silêmanî, asking him for protection. And although the US consulate official promised to support him, Kawa had already slipped into a pool of hopelessness at that point. He was expecting his assassins to arrive at any moment. He wrote, “After the assassinations of [journalists] Soran Mama Hama and Sardasht Osman, it’s my turn now, I’m nothing more than them.”

He had initiated several legal proceedings against those responsible for the threats, but nothing ultimately prevented his tragic death.

Kawa spent the last days of his life torn between the joyful anticipation of meeting his firstborn child, still in his mother’s womb, and hellish trepidation in awaiting his would-be killers. And in the end, the killers arrived before his son.

On December 5, 2013, around 9 P.M., someone knocked on his mother’s door. She opened the door to a group of men claiming to be Kawa’s friends. They said they just wanted to see him. His mother called on him, and when Kawa stepped outside, the men opened fire. They shot him seven times in front of her. He died there, in his mother’s arms.

On December 8, 2013, Kawa’s family filed a lawsuit in Kalar court against Mahmoud Sangawi, accusing him of being one of the main figures behind the assassination. Sangawi was briefly detained in January 2014 but was released when they could produce no evidence.

On March 4, 2014, the family filed a lawsuit against Adnan Hama Mina. Like the case against Sangawi, they accused Hama Mina of being behind the assassination. After some proceedings, the court cleared Hama Mina and decided he was innocent, as no one would testify against him.

Seven months later, on October 26, 2014, a criminal court sentenced a man named Twana Khalifa to death for the murder. Khalifa originally confessed to the murder, saying he killed Garmyani because the journalist belonged to the Communist Party, which he blamed for the death of two family members. Despite the original confession, Khalifa appealed the court’s decision. Later, on December 5, 2015, the court changed Khalifa’s sentence from a death sentence to a life sentence.

Another defendant, who was not named in news reports, was acquitted for lack of evidence.

After sentencing Khalifa, the court closed the case. However, there is no clear date of when exactly the case was closed; even the Garmyani’s family is unaware of this detail.

In 2018, five years after his killing, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) called on the Kurdish and Iraqi authorities to reopen the case:

“We call for the investigation to be reopened in order to shed all possible light on this murder and identify the instigators,” said Sophie Anmuth, the head of RSF’s Middle East desk

“We, as Kawa’s family,” Shirin Amin said, “continue to view PUK military official Mahmoud Sangawi as the main person who is responsible for the crime. We have sufficient evidence to support our claim. We also believe that certain powerful individuals within the PUK party were complicit in the crime by covering it up and allowing the masterminds of the crime to continue enjoying impunity.

“The Kawa Garmyani case, like those of many other murdered journalists and peaceful protesters of freedom, remains open until those who ordered these crimes are finally brought to justice. As Kawa Garmyani’s family, we continue our quest for the truth. We were able to meet with his killer [Twana Khalifa] in prison and obtain information about the assassination in detail; and those who were accomplices in covering up the crime; the serial number of the gun used to kill him; the brand of the car and its number plate. We also filed a lawsuit outside Iraq, in a Washington court, two years ago against the perpetrators, after having lost hope of obtaining justice in the courts of the Kurdistan Region [of Iraq].” Shirin Amin told The Amargi

As Reporters without Borders has written, Garmyani’s death is not a standalone incident; rather, it is one of many assassinations aimed at silencing critical voices and intimidating independent journalists.

Kawa’s Legacy

Azad Osman remembered those early, uncertain days in 2010, when he and a group of young journalists, rich in ambition but poor in resources, established Dang Radio. “For us, it was a huge project at the time – the first independent radio experiment in the region,” he said. “Kawa was working in another newsroom then, but despite his own commitments, he consistently supported us.”

In every memory, Kawa appears as he lived: principled, determined, and deeply committed to the cause of independent journalism. He was especially active in organizing events commemorating the assassinations of journalists Sardasht Osman and Soran Mama Hama, standing among those who planned, prepared, and mobilized the public. “He was one of the organizers, one of the people who made things happen,” Osman noted. Kawa Garmyani’s legacy continues to ripple in the lives and work of those he inspired – like Azad Osman, who remembers not only the tragedy of his assassination but also the fierce, generous spirit that defined his life, “Kawa was more than a colleague. He was someone who showed us what solidarity truly means.

Diyar Azeez Shareef

Kurdish writer and journalist based in France, RSF correspondent for the Kurdistan Region since 2011. Active since 1997, including serving as Hawalti’s editor-in-chief in 2007. His work centers on human rights, anthropology, and literature. Author of Anthropology, Anthropological Concepts, States of Mind, and the translated Dialogue with Contemporary Thinkers. He also translated Social Anthropology into Kurdish.

![[The Amargi Exclusive] Investigating the Syrian Army’s Abuses](https://cms.theamargi.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/AFP__20260118__934D2KE__v1__MidRes__SyriaConflictKurds.jpg)