Prolonged Isolation: The “Well-Type” Prison Model in Turkey

How can anyone spend 23 hours a day in a cell where they can take only six steps? In Turkey, this question has entered public debate with the introduction of a new prison model, featuring single and three-person cells engineered to block almost all daylight. The state defends the system on the grounds of “high security” and “preventing escape risks,” while human rights organizations argue that such practices amount to severe solitary confinement and inhuman treatment, in violation of human rights.

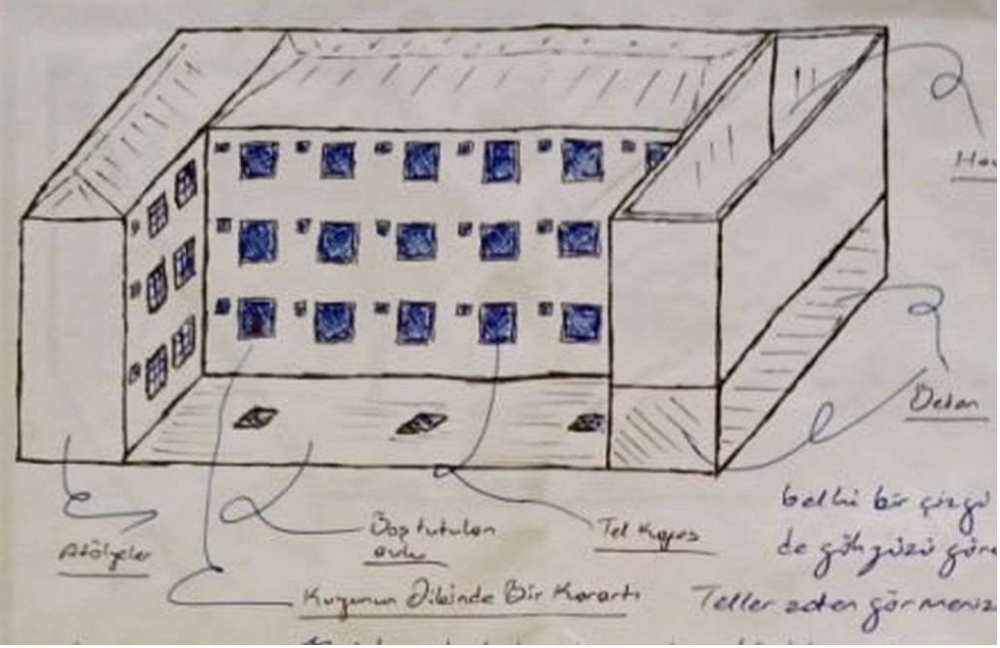

Referred to as “well-type” by prisoners themselves, these facilities are officially categorized into three groups: High Security, S-Type, and Y-Type. According to the most recent data from the Turkish Ministry of Justice, there are currently 42 such prisons across the country: 22 High-Security Prisons, 7 S-type, and 13 Y-type. The construction of these prisons began in 2020; they were designed with the aim of social isolation and segregation.

Why is it called the “well-type”?

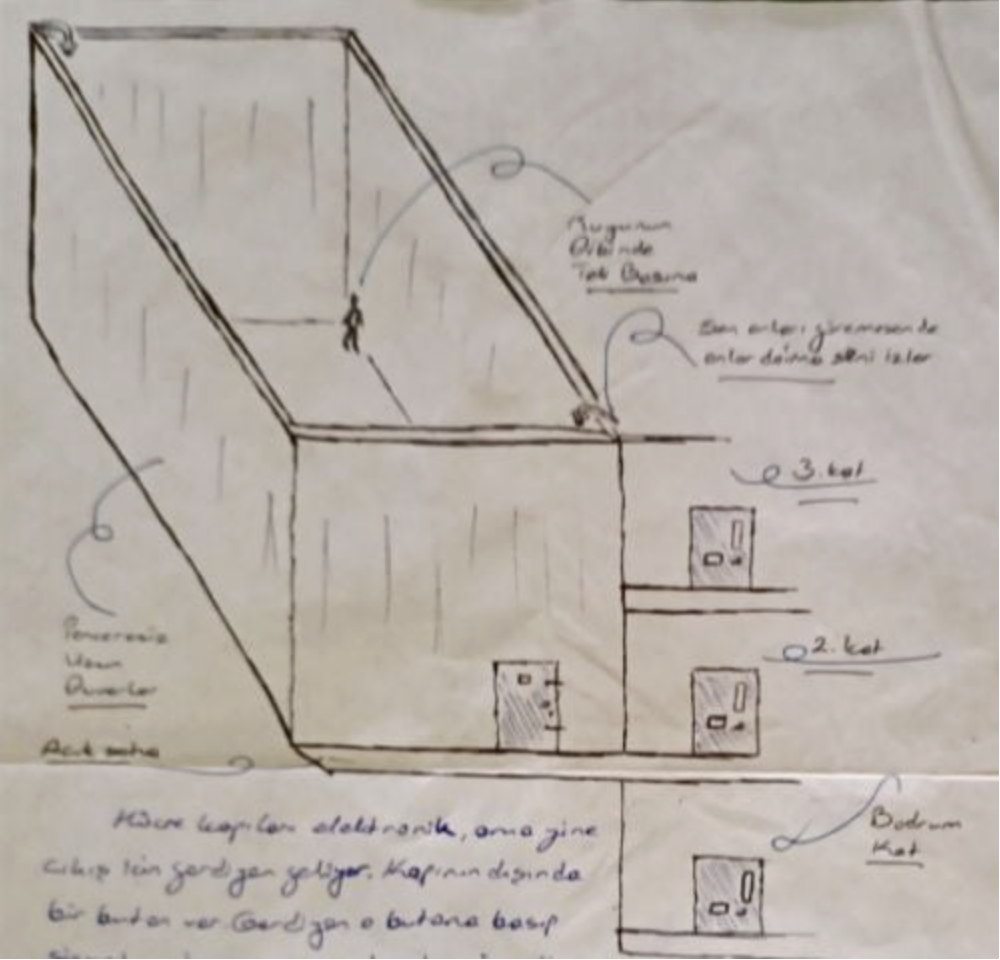

The “well-type” prisons consist of a three-story structure. Most of the cells are designed for one person; only a small portion is used for three people. Each cell is 12–13 square meters in size — just wide enough to take six steps. The only source of air and light is a single window, which opens onto an empty space resembling an apartment air shaft. In front of this window is a metal plate with holes so small that not even a pinky finger can fit through them.

Prisoners spend 22.5 to 23 hours each day in these cells. They are allowed outside for only one to one and a half hours a day when they are taken individually to another concrete area. This space is 63 square meters in size and monitored by cameras. Its walls rise up to 15 meters high, and the sky can only be seen through a wire mesh overhead. Prisoners describe feeling as if they are at the bottom of a well, with no shelter from the sun or rain. The prison administration controls the timing of this outdoor hour.

Constant surveillance

The doors are opened and closed electronically from a control booth located outside the cell block. Communication with prisoners is mostly via an intercom and button system. The aim of this setup is to minimize human contact as much as possible. In the three-person cells, cameras are installed, and prisoners are monitored almost continuously throughout the day. Although the Constitutional Court in Turkey has issued landmark decisions stating that the use of cameras in cells violates the right to privacy, these decisions are not enforced.

A prison within a prison

In the well-type prisons, everyone is effectively subjected to permanent solitary confinement.

According to human rights defenders, this architectural system violates the law. Regulations stipulate that only inmates serving aggravated life sentences are entitled to one to four hours of outdoor time per day. For other prisoners, cell doors are supposed to open after the morning headcount and close after the evening headcount. In the well-type prisons, everyone is effectively subjected to permanent solitary confinement. Prisoners are exposed to lasting isolation that goes far beyond imprisonment itself, effectively living in a “prison within a prison.”

According to lawyer Naim Eminoğlu from the Contemporary Lawyers Association, the well-type prisons have no legal basis and violate the Turkish Execution Law, the Constitution, and international human rights treaties: “Article 2 of the Turkish Law on the Execution of Sentences states that ‘the execution of sentences shall be carried out in a manner compatible with human dignity.’ This new practice directly violates this law. Moreover, there is no regulation, explicit by-law or implementing decree in the legislation that defines the well-type prisons. Even if there were, these prisons would still be unconstitutional, because Article 17 of the Constitution explicitly prohibits torture”, he told The Amargi.

Under international law, solitary confinement in this form amounts to torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. The well-type prisons are therefore in violation of the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (also known as “Mandela Rules”).

No defined crime category

The initial justification for opening the well-type prisons was the increasing number of inmates facing aggravated life sentences in Turkey. However, over time, the scope rapidly expanded — from ordinary prisoners in facilities that were damaged in the February 6, 2023, earthquake, to cartoonists from the satirical magazine Leman, and even to Murat Ongun, the former spokesperson of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality.

During a visit to the Çorlu Karatepe High-Security Prison Facility, the Human Rights Center of the Istanbul Bar Association documented widespread rights violations in these facilities. The report notes that the “right to social interaction,” which should be granted for up to ten hours per week according to regulations, is not provided at all, while the right to exercise is limited to only one hour per month. Restrictions on books and pens, arbitrary bans on correspondence, and constant surveillance further restrict prisoners’ lives.

Impact on human health

The gravest consequence of these restrictions is seen in the physical and mental health of prisoners.

The gravest consequence of these restrictions is seen in the physical and mental health of prisoners. Speaking to The Amargi, Ümit Efe, the Istanbul Representative of the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey, explains that it is extremely difficult for individuals to remain healthy in these facilities: “For individuals who have so little access to sunlight and are deprived of sensory and perceptual stimuli, musculoskeletal disorders, sensory impairments — particularly in vision and hearing — and psychological breakdown become inevitable. Orientation to place, time, and space can deteriorate.”

According to Efe, the demand from human rights advocates is clear: “Penal regimes must ensure the mental, physical, and social integrity of prisoners, and provide humane living conditions.”

Slowly driving prisoners insane

Oktay Kelebek is one of those who have endured the extreme isolation of the well-type prisons. He was held in the İzmir Buca Well-Type Prison with fellow detainee Cem Dursun and 78-year-old prostate cancer patient Mehmet Güvel. Kelebek tells The Amargi: “The sole purpose is to keep us under surveillance 24 hours a day. It is an environment where disorganization and individualism are imposed. They throw prisoners into a well and, in that silence, try to drive them insane and kill them over time.”

Kelebek and Dursun went on a hunger strike to draw attention to these conditions and ended their protest on the 181st day after securing the transfer of Mehmet Güvel to another prison.

Inside a glass box

In the well-type prisons, not only prisoners but also their visiting relatives face harsh security procedures. The sense of isolation extends into the visitation rooms. Prisoners and their visitors are placed in rooms enclosed on all sides with glass and guarded by prison officers. Speaking to The Amargi, Ferdi Sarıkaya, a member of the Association for Solidarity with Families of Prisoners and Convicts (TAYAD), recounts: “It feels like we are inside a glass box. We are under constant camera surveillance.”

Protests inside and outside

Despite warnings from lawyers and human rights defenders, the Turkish Ministry of Justice and the Directorate General of Prisons and Detention Houses have yet to issue an official statement regarding the well-type prisons. Meanwhile, resistance is growing both inside and outside the prisons. While hunger strikes continue in prisons, families from the Association for Solidarity with Families of Prisoners and Convicts have been gathering in public squares for weeks to amplify prisoners’ demands. Their message is clear: shut down the well-type prisons and uphold the basic human rights of prisoners.

At Antalya High-Security Prison Facility, Serkan Onur Yılmaz and Ayberk Demirdöğen began their hunger strikes months ago. Ayberk Demirdöğen, one of 10 prisoners currently on hunger strike, reached his 198th day and announced that as of October 1, he would take his protest to a new level by refusing even water and sugar. Serkan Onur Yılmaz, meanwhile, is on his 320th day of hunger strike. His lawyer, Naim Eminoğlu, says Yılmaz’s health has reached a critical point: “He is struggling to breathe; his respiratory and circulatory systems have deteriorated. He can only attend visits in a wheelchair, and nerve damage in his feet has worsened.”

Yılmaz has been transferred to Bolu F-Type Prison, while Demirdöğen has been moved to Kırıkkale F-Type Prison; however, their protests continue. Their demand is the transfer of eight prisoners who remain in Antalya High-Security Prison Facility out of the well-type facilities. According to lawyer Eminoğlu, the situation is extremely dangerous, and the demands must be urgently addressed.

Rengin Azizoğlu

Rengin Azizoğlu is journalist and news editor based in Istanbul.