MP Tanrıkulu Says Turkey Moves from “an Electoral Autocracy to an Autocracy with Controlled Opposition”

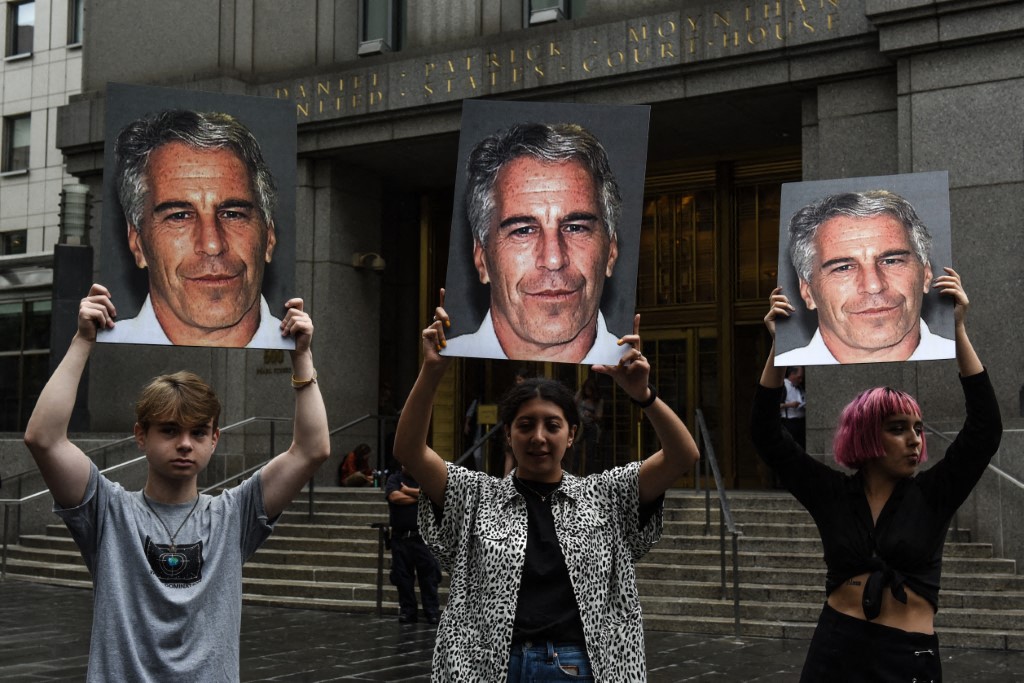

Picture credit: Sezgin Tanrıkulu’s official Facebook page

Sezgin Tanrıkulu, deputy of Turkey’s main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), spoke with The Amargi on 9th September 2025 about the increasing pressures on his party —including the appointment of a trustee to the İstanbul Provincial Presidency and the raid on its provincial building— and their impact on the National Solidarity, Brotherhood, and Democracy Commission, a parliamentary body established to facilitate the resolution of the Kurdish issue in Turkey. He discusses the challenges facing Turkey’s democratic politics, the Kurdish question, and the prospects for the Commission’s ongoing work.

The Amargi: How do the rising pressures on the CHP impact the work of the National Solidarity, Brotherhood, and Democracy Commission?

Sezgin Tanrıkulu: Today, the CHP faces an extra-legal siege. The reason is simple: the CHP is the only alternative capable of changing the current political administration through the ballot box. That is why, increasingly since 31st March, an unlawful approach has been directed both at its institutional identity and its political actors. The most recent example of this process, carried out using the judiciary, was the raid and trustee appointment attempt targeting the Istanbul Provincial Presidency building1.

The fundamental reason is this: the Turkish government is becoming increasingly authoritarian, moving from an electoral autocracy to an autocracy with a controlled opposition. In the 31st March 2024 local elections and subsequent developments, the CHP did not comply with the line dictated by the Justice and Development Party (AKP). It maintained its stance both at the level of local actors and in the central headquarters. In response, starting on 30 October, judicial operations were launched—from Esenyurt, Beşiktaş, and Beykoz to the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality—and continue to this day.

We should consider this alongside the issue of the Commission and Turkey’s Kurdish question. It is clear that there is a significant difference between our perspective and that of the AKP on these matters. In the Commission, the AKP has consistently stated: “Turkey has no democracy problem. Turkey has a democracy progressing along its natural course. Turkey has no Kurdish issue; this problem has been resolved by the AKP. Turkey only has a terrorism and weapons problem. The Commission’s mandate is limited to this.”

The CHP, on the other hand, insists that Turkey does have a democracy problem. Turkey does have a Kurdish issue.

The CHP, on the other hand, insists that Turkey does have a democracy problem. Turkey does have a Kurdish issue. The Kurdish question is one of the most important components of the broader democracy problems. Therefore, unless simultaneous steps are taken on these matters, the process cannot be successfully concluded. We have also expressed this view in the Commission.

If extremely anti-democratic pressures continue against the CHP and other opposition forces, it is impossible for a process aimed at societal peace to proceed simultaneously. The AKP needs to make a political choice here: are they genuinely in favor of peace and social reconciliation, or will they continue to pursue violence as politics? The future of the Commission will depend on the AKP’s decision.

…it is not possible for the ruling AKP to continue the Commission on its own terms, independent of such perspectives

So far, seven meetings have taken place, and they were important. But a certain picture emerged in these meetings: those who attended and were heard —including a former Parliament speaker— largely confirmed that Turkey has a democracy problem and that the Kurdish question cannot advance without addressing these broader issues. Therefore, it is not possible for the ruling AKP to continue the Commission on its own terms, independent of such perspectives. After all, in an environment where the main opposition party’s central headquarters are under siege and the Istanbul Provincial Presidency is practically taken over with tear gas and tanks, who can engage in democratic politics in Turkey?

Due to current developments, the solution process is effectively on hold. It is clear that it cannot move forward under the existing legislation and ongoing conditions. For example, the closure case against the HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party) is still pending in the Constitutional Court and has not been resolved. In this environment, it is difficult to see how politics can function without democratic practice.

The Amargi: The Kurdish peace process seems to have reached a deadlock, with developments in Syria and their repercussions in Turkey cited as a major factor. How do you assess this situation?

Tanrıkulu: From the outset, there have been two major dilemmas. First, there is no guarantee for democratic politics in Turkey. Will the ruling AKP make a choice in favor of democratization? What we are experiencing today presents a picture suggesting that no step will be taken in this direction. The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) symbolically laid down their arms, and disbanded the organization, declaring that they would no longer use armed methods; they did not abandon their political claims but announced their intention to engage in politics. For them to pursue democratic politics, in whatever form, the space for democratic politics in Turkey must first be guaranteed.

The situation of the Kurds in Syria is a red line for Kurds in Turkey. Turkey’s Kurds do not want the situation of Syrian Kurds— having paid such a heavy price—to be destabilized.

Second is the issue of Syria. The situation of the Kurds in Syria is a red line for Kurds in Turkey. Turkey’s Kurds do not want the situation of Syrian Kurds— having paid such a heavy price—to be destabilized. Furthermore, in this environment, it is not rational to expect them to submit to a state that does not represent Kurds and has no army and no constitution. The status of citizen rights in Syria remains unclear. Is there even a constitution in Syria and a defined state? Why would Kurds surrender to an army recruited from former jihadists? Who would expect them to submit today to a force that yesterday beheaded people, interfered in their lands, harmed their families, and abducted and raped their women, just because they now wear green camouflage uniforms? This is one of the greatest obstacles in the process.

The Amargi: According to a recent survey (conducted by GÜNDEMAR on 3–4 September 2025 with 1,170 people in 26 provinces), 50% of the CHP base support the party remaining in the Commission, 37% support leaving, and 13% have no opinion. Does this indicate a division within the CHP regarding the party’s extra-parliamentary political contacts or alliances?

“How can the process move forward while Selahattin is still behind bars?”

Tanrıkulu: In this environment, the fact that 50% say “the party should stay in the Commission” is a major success. The reasons why 37% oppose it are clear; nevertheless, it is highly significant that half of the CHP electorate considers contributing to the Commission appropriate. This is true across all political parties; none have yet managed to fully engage their base 100% in the process. The reason for this is the AKP’s extra-legal methods. The situation is also difficult for Kurds; for example, Selahattin Demirtaş [former HDP co-chair] is still in prison, and European Court of Human Rights rulings have not been implemented by the government. Kurds ask, “How can the process move forward while Selahattin is still behind bars?”

The Amargi: Does this “extra-legal siege” aim to leave the CHP politically powerless in the ongoing Kurdish process?

Tanrıkulu: Even if this is the aim, that is not possible. We have clearly taken the initiative and stated our position on Turkey’s Kurdish issue. That is why we are in the Commission. The AKP’s intention was not to prevent the CHP from participating; we did participate. However, they are doing everything they can to make the CHP withdraw so that all responsibility falls on our party if the process fails.

[Regarding the apparent contradiction between the crackdown on the CHP and the ongoing Kurdish peace process] At this point, the main responsibility lies with the DEM Party; they are the ones leading the process and holding the mission. Therefore, it is their duty to warn relevant actors —publicly or privately— about steps that have not been taken. They are also the ones with direct access to İmralı [Abdullah Öcalan] and holding closed-door discussions with the government.

The Amargi: Are there any concrete steps, like legislation proposals, on the agenda of the Commission? Have you been able to move to the stage of concrete steps?

Tanrıkulu: We have not. As I mentioned in previous Commission meetings, laws related to integration2 need to be drafted, and the relevant ministry must provide the Commission with information. If necessary, Parliament should convene extraordinary sessions to work on these laws.

A period of special sessions to hear the ministry’s views on the legal framework and the opinions of political parties should begin. The Commission should meet not just one, but perhaps five days a week. At present, there is no concrete agenda regarding the return [and reintegration of former armed group members] or truth and reparation processes.

- In mid-September 2025, following the CHP Istanbul raid, the government launched a corruption probe in Bayrampaşa, another CHP-run İstanbul district municipality, detaining Mayor Hasan Mutlu and 43 municipal staff. Later, despite the mayor’s detention, CHP managed to retain control of Bayrampaşa in a district council vote on September 21, 2025. ↩︎

- In the context of Turkey’s Kurdish peace process, integration typically refers to the demobilization of Kurdish armed groups, their transition into legal political activity, and the inclusion of Kurds in state structures through democratic reforms, cultural recognition, and legal protections. ↩︎

Serap Gunes

Serap Güneş is a freelance translator and writer based in Istanbul. She holds a PhD in International Relations and European Politics from Masaryk University, where her research focused on minority rights and EU–Turkey relations. Her work has appeared in both academic journals and independent media outlets.