Ararat: A Kurdish and Roman Story at the International Architecture Exhibition

Picture Credits: Antonella De Biasi

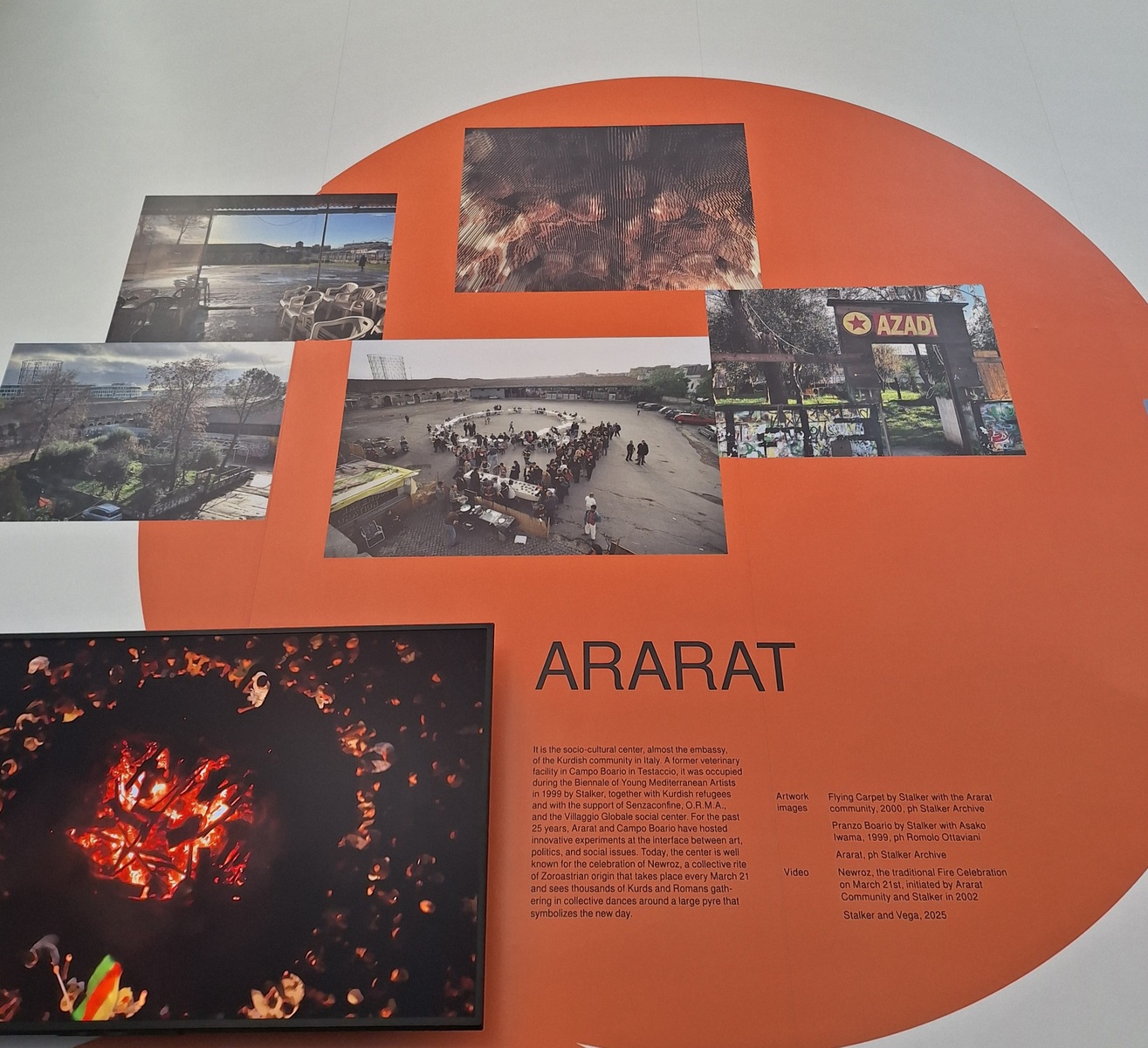

Roman Kurds, with the architect collective Stalker, have created the Ararat project, which is currently on display at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 – open until November 23.

The first Kurds who contributed to Ararat arrived in Rome in 1999. Then, gradually, due to the Turkish government’s repressive anti-Kurdish policies, many others came: refugees, poets, artists, musicians, journalists. Young men and women with their whole lives ahead of them, and who, in the last 25 years, have become “Roman Kurds”.

Sitting in Testaccio, a working-class neighborhood of Rome, Ararat has served as a socio-cultural center for the Kurdish community in Italy and has almost become like an embassy for a stateless people.

Since its founding in 1999, Ararat has blossomed. Sitting in Testaccio, a working-class neighborhood of Rome, Ararat has served as a socio-cultural center for the Kurdish community in Italy and has almost become like an embassy for a stateless people. Its name, deeply tied to the Kurdish identity, is an homage to the Biblical and historic mountain that is beloved by Kurds, Armenians, and others.

It has been at the heart of the Kurdish community’s social and cultural activities in Rome and has been the scene of innovative experiments, combining art and social issues. It is widely known for its Newroz celebrations on March 21st – the Kurdish New Year that has mythic origins and which brings together thousands of Kurds and Romans to dance around a large pyre, symbolizing the new day.

A Kurdish and Roman Story

The Campo Boario in Rome, Ararat’s home, was abandoned in 1975. It sits in a central but marginalized area, in a pocket of ancient and modern Roman history: between the Tiber River, the Aurelian walls, and the railway. Over time, it transformed into a haven for refugees, migrants, and, in particular, the Kalderasha Roma community, which was evicted in 2004.

In 1990, it became home to the Villaggio Globale, a self-managed social center committed to building an inclusive and transcultural society. During Ararat’s founding, Villaggio Globale, along with other local associations, supported the Kurds and Stalker occupying the space. Today, the Villaggio hosts artistic and craft workshops.

In addition to Ararat and other associations, Campo Boario is also home to the Città dell’Altra Economia (City of the Other Economy), the Academy of Fine Arts, and stables for horses and “botticelle”, typical Roman gigs for tourist use.

For 25 years, the Campo Boario complex has been the subject of a redevelopment project that has struggled to take shape. In lieu of redevelopment, the space has served as an arena where informal practices and institutional projects clash.

“Our modernity and contemporaneity are also leaving us with a lot of ruins,” said Lorenzo Romito, architect and founder of Stalker, at the Venice Biennale exhibition. “Social movements are those biological forms of struggle for life that reclaim unsuitable environments. And precisely because of the inadequacy of these environments, they invent innovative forms of co-evolution, and Ararat is one such case.”

Romito and his colleagues have created ample opportunities for interaction with the Roman-Kurdish community and architecture students from the nearby university: ”We shared the very constitution of Ararat with the Kurds, starting with the occupation of the space and the desire to immediately turn it into a place of research.”

The 2025 Venice International Architecture Exhibition is titled “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.” It is curated by Italian architect and engineer Carlo Ratti, who explained, “To face a world in flames, architecture must be able to utilize all the intelligence that surrounds us.”

At this year’s exhibition, Ararat is part of the Austrian Pavilion project called “Agency for better living”, which looks at two European cities, Vienna and Rome, to demonstrate different forms of “intelligence” that can help find solutions: Vienna is a city that takes care of its inhabitants. Through a top-down process, it ensures that anyone looking for affordable housing can obtain it. Rome, on the other hand, is a city where, thanks to hard-won bottom-up processes, informal forms of living have emerged with often surprising organizational models.

The Viennese system generates security, while the Roman system generates an active civil society.

Faced with the challenges of the neoliberal city, the city of finance, the commodification of territory, touristification, and climate change and immigration, the exhibition offers a comparison between public institutions that know how to manage a city (Vienna) and social movements that have managed to organize themselves in ways that have produced exemplary cases (Rome).

The exhibition presents 100 projects through information sheets; seven of which are deemed exceptional due to their struggle and their dynamics of social and cultural organization from the bottom up. Among these seven is the Kurdish experiment of Ararat.

“Together with our Austrian colleagues, we discussed Vienna and came up with a radical interpretation,” Lorenzo Romito explained. “It was certainly a biased choice, but Vienna is described as a model of public planning, while Rome is seen as a place lacking good, long-term public planning and as a history of social struggle that nevertheless produces innovation in the forms of living.”

The exhibition uses the symmetry of Josef Hoffmann’s pavilion to get its point across: one side tells the story of the Viennese model, the other that of Rome.

It channels a topical conversation, as across Europe and around the world, there is a major housing crisis, barring people from buying or renting at affordable prices. Simultaneously, people are communicating their need and want for a higher quality of life more acutely.

And while public housing is disappearing, investment funds are taking over, and the market dictates the rules without restraint, and cities are becoming increasingly unlivable. This is the challenge that contemporary architects are grappling with.

“We have accompanied the narrative in the exhibition with a history of modern Rome,” Romito said, “which is the story of a rejection of this very genius loci of the city.

“We have accompanied the narrative in the exhibition with a history of modern Rome,” Romito said, “which is the story of a rejection of this very genius loci of the city. The city regenerates itself with nature, so we must think about leaving space for it. And the city regenerates itself with foreigners: Rome has granted citizenship to all foreigners since its foundation; Rome regenerates itself through the construction of common assets.”

Kurdish-Romans, Roman-Kurds

The Roman movements for the right to housing are unmatched in Europe in terms of size, continuity, and resilience. And within these dynamics, there is a piece of the Middle East and thousands of Kurds who have passed through Campo Boario and Ararat over the years, and who have contributed to imagining and creating new housing and community realities.

Today, many people in Rome know that March 21st is the day for celebrating Newroz, the Kurdish New Year. It has become a collective ritual thanks to the Ararat socio-cultural center, which has helped to make Kurdish culture part of Rome’s fabric.

Antonella De Biasi

Antonella De Biasi is an Italian journalist, author, and writer. With a background in communication sociology, she has been working on Kurdish issues for more than 20 years. She works as a consultant and press officer for several Italian and European associations and institutions. She edited the book Curdi (ITA, Rosenberg & Sellier) and wrote the novel Zehra; La ragazza che dipingeva la guerra (ITA, Mondadori). She lives between Rome and Venice.